“Walking is man’s best medicine.” — Hippocrates

For a long time walks in baseball were considered a mistake, an accident caused by poor aim. The pitcher was wild and if he couldn’t throw three strikes before he threw four balls, Mr. Batter was directed to trot down to first base.

When the rules of “base ball” were first being codified, there were no walks. The hitter was allowed to instruct the pitcher to toss the ball where the batter wanted it. Eventually, after this back-and-forth exchange of accommodation between the two opposing players, the ball was to be put in play. The founding fathers of the game wanted action.

But after decades of sporting evolution, eventually baseball watchers realized that taking a free pass was a skill as much as an incidental occurrence. Some batters drew more walks than others. Some, like Babe Ruth, did so in large part because pitchers were petrified to throw the sphere near a meaty part of the plate. Others, not sluggers at all, also seemed to be able to accumulate walks at a high rate. Some of these players were impish little fellas who wouldn’t scare a mouse. Their teammates recognized them as having “a good eye.” One of them, a middle infielder in the 1920s named Max Bishop, was even called “Camera Eye.”

For some strange reason four of the best players in baseball history at drawing walks played at the same time and were each known by the first name Eddie. Each of these men made their living at one of the four corners of the infield.

I’ve long wondered at this odd coincidence. We’re not talking about four players who were sort of good at getting on base via the walk, we’re talking about four of the greatest ever, each of them sharing the same first name and playing at almost exactly the same time, three primarily in the National League, and one exclusively in the American League, but the four were all in uniform in the years around and after World War II and into the 1950s.

Here’s a look at this quartet.

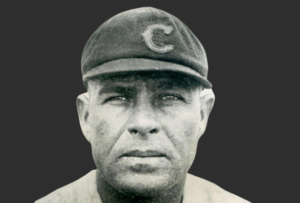

Eddie Stanky

In eleven seasons in the big leagues, Stanky posted a .410 on-base percentage, a figure higher than all but sixteen men when he retired in 1954. Stanky ranks fifth all-time in baseball history in walk rate (for players whose career started after 1900), earning 128 free passes per season for his career. Largely forgotten today, Stanky still ranks among the greatest second basemen of all-time.

How did he draw so many walks? It wasn’t because he was imposing. Stanky stood five-foot, seven inches tall and weighed slightly more than 170 pounds. Many sources claim he was an inch taller, but that was hyperbole doled out by Eddie and the public relations of the teams he played for. The secret to Stanky’s success at drawing walks was twofold: stand close to the plate and never swing at a pitch out of the strike zone. He had a discerning eye — in one minor league season during the Gret Depression in the Piedmont League, he walked 99 times in 90 games. By standing on top of the plate, little Eddie dared enemy pitchers to come inside. They sometimes did, but usually for vengeful reasons — Stanky was one of the most hated players in the National League.

Stanky was one of baseball’s toughest and grittiest players. He was known for sliding into bases with his spikes high and for elbowing opposing runners from his position in the middle of the infield. The little guy was at his best at second base, but unfortunately for him he was stuck in the Dodgers and Cubs farm systems in the 1930s and unable to break into the big leagues because those teams were well stocked at second and short. Also, Stanky never hit for a high average and he never impressed that much even when he did get a hit. He was a “punch-and-judy” type hitter who was valued for his glove and grit. But not until the big leagues were emptied of much of their talent during World War II was he given a shot with the Cubs in 1943. By that time, Stanky was 27 years old and had nearly died a few times from being hit in the head by pitches in the minor leagues. He made the most of his chance with the Northsiders, but in 1944 he was dealt to the Dodgers, who had previously owned his rights.

Brooklyn was the perfect place for Stanky, who soon earned several nicknames due to his spitited, hot-headed play. One was “Muggsy,” another was “Stinky,” and the most prominent was “The Brat,” which followed him the rest of his life. In 1945 he drew 148 walks, in ’46 he drew 137, and he topped the 100 mark four more times. In ’47 he was a key reason that “Da Bums” won the flag, and Stanky finished 13th in MVP voting. His most amazing statistical year occurred in 1950 when he was in a Braves uniform. That year Stanky hit .300 with 144 walks for a lofty .460 on-base percentage. He reached base 314 times that season.

Had he had the chance to free himself from the minor leagues in the 1930s, say from the age of 22 to 26, Stanky probably could have added another 500 or 600 more walks to his final ledger, which came in at 996. There are all sorts of other wonderful things you should know about Stanky, like his feud with Leo Durocher, his part in the sign-stealing that helped the ’51 Giants win the pennant, the many injuries that nearly ended his career at various times, and the many clubhouses in which teammates grew to hate Eddie. But we’re out of time.

Eddie Joost

Edwin David Joost (his surname was pronounced YOOST) was born nine months after Stanky and on the opposite coast (Edward Raymond Stankiewicz hailed from Philadelphia), but he debuted in the big leagues seven years before Stanky. Joost had the fortune of being signed and developed by the Cincinnati Reds, one of the few NL clubs Stanky never played for. A shortstop with highly-regarded defensive skills, Joost played on the 1939-40 Cincy teams that won two pennants and a title in the latter year, but by that point he was a utility infielder. His bat wasn’t considered formative enough to play every day.

After a brief trial with the Braves and then action in WWII in the U.S. Army, Joost was at a crossroads in 1946. He was nearly 30 years old and had hit .185 in his most recent full season. As a result, Joost failed to receive any offers, so he went to the Philadelphia Athletics, where he met the man who would change his baseball career. Connie Mack immediately loved little Eddie Joost and he gave him the starting shortstop job. In his first season with Mr. Mack’s club in ’47, Joost hit a measly .206 but still managed a .348 OBP because he walked 110 times. It was the first of six straight seasons where Joost would walk at least 100 times and play short for Mack. The A’s were a dreadful team, but Eddie was a standout, making the All-Star team twice and earning MVP votes five times. In 1948 he was tenth in AL MVP voting when he slugged 16 homers and walked 119 times. He had an even better campaign the following year: 128 runs, 23 homers, 81 RBIs, 149 walks, and a .429 OBP. His OPS that season was an eye-popping 883.

Joost was an All-Star twice, and five times with the A’s he got significant MVP support, finishing as high as tenth. Something had happened to Joost when he came back from the Army, he was a better hitter by a mile. In contrast to most middle infielders, Joost had all of his best seasons after his 31st birthday.

What happened was that Joost took a liking to his new home: Shibe Park. While he had hit only three homers in more than 200 games at Crosley Field in Cincinnati, Eddie was practically Vern Stephens in his years in Philadelphia. In nearly 500 games at Shibe he hit 71 homers and had a .433 SLG with a cool .400 OBP. Not shabby for a “defense-first” shortstop. He rates 21st all-time in walk rate, earning 107 walks per season.

Eddie Yost

“He used to get walks in batting practice.” — Bucky Harris about Eddie Yost

He was known as “The Walking Man” and he even though he stopped playing baseball when John Kennedy was in the White House, Yost still ranks 11th all-time in free passes. His walk rate is just behind that of Stanky’s, ranking seventh all-time with 124 free passes per season.

Yost’s peak came in 1950 when he posted an insane .440 on-base percentage despite hitting below .300. That season, Eddie accumulated 141 bases on balls, the first of eight seasons he topped 100, and the first of six times he led the American League in that category.

For most of his career, Yost toiled for the Senators, earning many fans in D.C., including President Dwight Eisenhower, who listed Eddie as one of his favorites. Yost stuck at third base almost exclusively in his career because he lacked the range to play short or second and he never was that great with his footwork. Early in his career he had an erratic arm but he tamed it a bit as he went along.

He spent 14 seasons with the Senators and he ranks second all-time in on-base percentage for that team with a mark of .389 on the strength of 1,274 walks. In 1956 he had the lowest batting average (.231) for any player who has ever had a .400 OBP in a single season. That year he drew 151 walks in 152 games. It was one of four times in his career that Yost had more walks than hits. He was a valuable leadoff man even though he was not a fast runner: three times in his career he had streaks of ten games in which he drew at least one walk. Yost also had three streaks of more than 30 games in which he got on base at least once. His longest streak was in 1953 when he got on base by a hit, walk, hit by pitch, or reached via error in 43 straight games.

A staple for the woeful Senators, only five players in franchise history appeared in more games for the Senators than did Yost. After the ’58 season he was dealt to Detroit, which surely saddened Ike but delighted the Tigers. He led the AL in runs, walks and OBP that season and also took a shining to Briggs Stadium, slugging a career-best 21 home runs. Usually, Eddie was good for 10-12 homers per season, and rates among the 100 greatest third basemen in baseball history.

Yost was still a valuable offensive player when he hung up his spikes as a player, but he didn’t have a defensive position he could play anymore, so at the age of 35 he was finished. But he’d been a popular player throughout his career and was considered a good baseball man. As a result he earned coaching jobs with the Angels,

Yost holds two interesting distinctions: he was the first batter to come to the plate for the Los Angeles Angels, serving as their leadoff man on opening day in 1961; and he is the only member of the original Senators to later manage the expansion Senators, which he did for one game in 1963 on an interim basis.

Eddie Lake

Lake’s walk rate of 106 per season ranks 23rd all-time, although he had the shortest career of our quartet, at least at the major league level. He spent 11 seasons in the minor leagues, bookending his MLB career, which spanned from 1939 to 1951.

Like Joost and Stanky, Lake was born in 1916, and he was the oldest of the three. He matriculated through the well-stocked Cardinals farm system in the 1930s, debuting for the Redbirds in 1939. After missing some time while serving in World War II, he emerged back with the Red Sox, but his breakout season came in ’46 when he became the Tigers everyday shortstop. That year he walked 103 times, one of three straight years over the century mark. He was a popular player in Detroit, even when his average dipped to a terrible low of .196 because he still managed to get on base to the tune of a .359 OBP. His .211 batting average in 1947 is the lowest ever by a player who had at least 600 at-bats. After he slowed and was released by the Tigers at 34, Lake felt he had a lot more baseball left in him. He played six more seasons of professional ball in the minor leagues, even slugging 27 homers for the San Francisco Seals in 1952.

There you have it — four Eddie’s, each an infielder who played before, in and around World War II, were infielders, and rate no lower than 23rd all-time in walk rate. Combined they averaged 465 walks per season.

Talk about a bunch of Walking Eddie’s.