What are the odds that George Springer will get thrown out trying to steal second base in the ninth inning with two outs tonight in Game Seven of the World Series?

Has to be a few million to one odds, right? Don’t hold your breath, Nationals fans, it’s not going to happen.

But there was another George, a Mr. George Herman “Babe” Ruth, who did just that in Game Seven of the 1926 World Series.

The decades have piled up, and it’s now been nearly a century, since Babe Ruth famously tried to steal a bag in the ninth inning of the World Series and failed. Called out, the Babe trotted back to the dugout in old Yankee Stadium as the St. Louis Cardinals celebrated their first World Series championship.

Talk about your bonehead plays, right?

Or was it? Is there a more simple explanation for Ruth’s dash for second base? Turns out there is.

According to The Sporting News, Ruth wasn’t stealing second base that afternoon in The Bronx. Nope. The hit-and-run play was on, and Ruth got hung out to dry when his teammate missed his pitch.

Let’s set the scene: the Cardinal were clinging to a 3-2 lead in the ninth inning at Yankee Stadium, which was only three years old at the time. There were two outs and Grover Cleveland Alexander was on the mound for St. Louis, primed to close out Game Seven.

No one called him by that name, though. He as known as “Ol’ Pete” to almost everyone, or “Alex” to his real close friends. He was one of the greatest pitchers to ever step on the rubber, and he owned the Yankees that Fall Classic. What Madison Bumgarner was to the 2014 World Series, Alexander was in 1926. He had already defeated the Yankees twice at Yankee Stadium, in Game Two and the previous day in Game Six. At 39, Alexander had lost little on his fastball, and he was wiser and more economical on the mound. Earlier in Game Seven, he strolled from the bullpen into a bases loaded mess and promptly struck out Yankee second baseman Tony Lazzeri with one of his sharp curve balls.

Alexander routinely set down the first two Yankee batters in the ninth, and as if the baseball gods were writing a script for the ages, that brought up Ruth. Earlier in the series in Game Four, the Great Bambino had slugged three home runs to lead the Bombers to victory. The following season, Ruth would clout an astonishing 60 home runs. He was at the height of his powers, a monster with a baseball bat in his hands. It was appropriate that the series would hinge on a battle between Alex and the Babe.

Alexander was smart enough to know that he didn’t want to challenge the great Yankee slugger. In the third inning against starting pitcher Jesse Haines, the Babe had put the baseball into orbit, sending a pitch deep to right-center field. Mindful of that, Alexander was cautious, but Ruth was a bit too anxious early and fell behind 1-2 after fouling off a pitch. The next two pitches were wide of the plate, fluttering breaking balls that Ol’ Pete hoped Ruth might lunge at. But the Yankee smasher laid off and ran the count full. On the 3-2 pitch, Alexander still refused to rely on his fastball. Perhaps feeling the fatigue of having tossed a complete game the afternoon before, Alexander went to his curve again, placing a pitch on the outside edge of the plate. Ruth wasn’t sure if it would be called for a strike, but hearing nothing from the umpire, he dropped his mighty piece of lumber and trotted to first base.

Bob Meusel was having a terrible game. In the fourth inning, the Yankee left fielder was slow to retrieve a single down the line and allowed a St. Louis runner to advance to third. A batter later, a lazy fly ball was hit to Long Bob and he camped under it in medium left. But just as the crowd thought the baseball would rest safely in Meusel’s glove for the second out, he dropped it. The misplay allowed a run to score and the baserunners to advance. the next batter singled in two more runs. Meusel was given one error, but he had actually made two poor plays in the inning. Now he stood at the plate in the ninth with Ruth a few steps off the bag at first base, and a chance for redemption.

Alexander must have decided he wasn’t going to lose such a pivotal game with his breaking ball. He started Meusel with a fastball that Bob was late on. At that point, something happened that has been forgotten to history. Apparently, Meusel signaled to Ruth for the hit-and-run. The Sporting News reported that “Meusel, after swinging viciously at the first pitch, put on the hit and run with the Babe on the next pitch.”

This is where the Babe’s reputation is exonerated. Where a mistake is corrected. Ruth wasn’t stealing second base. It wasn’t a lark, a moment of hubris. It was a set play called by the batter.

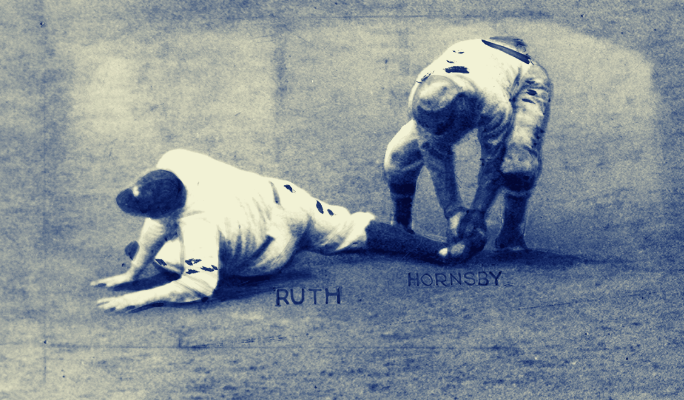

Alexander went to the fastball again with the same result: Meusel missing it on a big swing. Ruth got his jump and sped his piano legs toward second base. But at the moment he arrived, Rogers Hornsby also received a perfect throw from catcher Bob O’Farrell and slapped on the tag, getting Ruth on the right toe. The game was over, the series was over, the season was over.

It’s important to note that newspaper accounts of the game, where they detailed the game action, never called Ruth’s play a “caught stealing” and at the time they did not criticize Ruth’s conduct. It was a play to get the runner moving in a situation where the Yankees desperately needed a run against a pitcher who had dominated them.

But within a few years, at least by the 1940s, the play that ended the 1926 World Series was being reshaped. The story was retold and embellished. Much of the facts around that game, the things we hear about that game are false. Ruth’s foolish attempt to steal second base was one of those myths.

We were told that Pete Al;exander, fresh off his brilliant performance in Game Six, had celebrated and gotten drunk. And that he was still hungover (or drunk) when he was summoned into Game Seven.

We were told , by many sources, that Ol’ Pete never took a single warmup pitch, telling his catcher that he only had a few good pitches in his right shoulder.

It was implied by some sources that Alexander’s crucial strikeout of Lazzeri came with the bases loaded in the ninth inning.

And lastly, we were taught that Babe Ruth, the great slugger (but fat slob) had made a puzzling and stupid decision to try to steal second base with two outs in the ninth inning of Game Seven.

None of those things are true.

Cardinals’ manager Rogers Hornsby had told Alexander to lay off the booze after Game Six, explaining that he might be needed out of the bullpen, Ol’ Pete followed orders and was sober when he entered Game Seven. Later, a movie starring Ronald Reagan as Alexander, showed the great pitcher cautiously walking from the bullpen and into the game. He is forlorn because his wife is not at the game. That scene helped shape the myth.

It’s true that Alexander did not warm up in the bullpen. But that’s because the veteran pitcher usually preferred to loosen his arm on the actual mound. Which is what he did in Game Seven.

We’ve known for a long time who the hero of the 1926 World Series was, though some of the circumstances of that performance have been clouded in falsehoods.

But Babe Ruth has been wearing goat horns for too long. His steal attempt that ended the 1926 World Series was not a steal attempt. The real goat was Bob Meusel, who called for a hit-and-run and didn’t succeed in the “hit” part.