Opening Day is unique to baseball. Other sports have season openers, but baseball’s Opening Day marks the ceremonial beginning of spring. It may only be 1/162nd of the season, but fans and players alike admit there’s something special about the first game of the schedule. Every team starts the season with a clean slate, and you never know what you may see on Opening Day. It may be the beginning of a fairy tale season for your favorite team, the debut of a Hall of Famer, the unveiling of a new ballpark, or a spectacular performance, like a no-hit game.

That’s exactly what happened on April 16, 1940, when 21-year old Bob Feller threw the first and only Opening Day no-hitter, shutting down the White Sox at old Comiskey Park, 1-0. It was all the more remarkable considering the temperature was a chilly 35 degrees at game time and Feller was pitching on two days rest. In 1990, on the 50th anniversary of his feat, Feller recalled the details of that game. “I remember my last outing was an exhibition game in Cleveland on Saturday and I was hit hard. I had pitched very poorly, but on Opening Day I felt in good condition.”

“The first couple of innings I was pretty wild. In the second inning, I loaded the bases. Someone in the bullpen was warming up and the manager (Ossie Vitt) was getting ready to walk out to the mound. But I managed to strike out the last hitter on a full count.”

Feller also faced a challenge against White Sox’ shortstop and future Hall of Famer Luke Appling, who fouled off 15 pitches in one at-bat before he was retired. The no-hitter wasn’t Feller’s only success opening the season during his Hall of Fame career. The right-hander notched three shutouts in seven starts on Opening Day.

On April 14, 1915, Philadelphia A’s hurler Herb Pennock made a bid for Opening Day history. A crafty left-hander, Pennock no-hit the Boston Red Sox for 8 2/3 innings. In the ninth, with Pennock one out away, outfielder Harry Hooper beat out a high grounder past Pennock toward the middle of the infield, ruining what could have been the first Opening Day no-hit game.

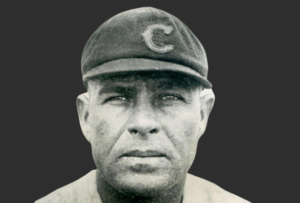

Other hurlers who took a run at no-hit Opening Day immortality include Lon Warneke, who went 8 1/3 hitless innings on April 17, 1934, for the Cubs, before Cincinnati’s Adam Comorosky collected a hit. Red Ames held Brooklyn hitless for 9 1/3 innings on Opening Day, April 15, 1909, but unfortunately his teammates failed to score a run and he lost 3-0 in the 13th, having surrendered four hits in the extra frames. Hall of Famer Robin Roberts came close to matching Feller’s feat on April 13, 1955, when he carried a no-hitter 8 1/3 innings before Giants’ infielder Alvin Dark spoiled his bid with a single.

Opening Day Aces

Roberts holds the major league record for most consecutive Opening Day starts for the same team (12), starting every Opening Day for the Philadelphia Phillies from 1950 to 1961. Upon his induction to the Hall of Fame in 1976, Roberts pegged the 1950 opener as one of the greatest Opening Day thrills of his career. “I’d have to pick the 1950 opener when we beat the Dodgers, 9-1, as the most thrilling for me from a team standpoint. We had finished well in 1949 and we had pennant hopes in 1950, so that first game made us all proud.”

Tom Seaver also started 12 straight openers, but with two different teams: the Mets and Reds. Jack Morris came within an eyelash of tying Roberts’ mark of 12 straight with one team. Morris started 11 straight openers for Detroit from 1980 to 1990, before tacking on three more for Minnesota and Toronto. Morris’s 14 straight Opening Day starts are a record.

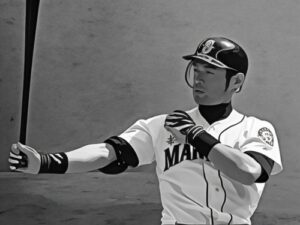

Seaver holds the record for most overall Opening Day starts, with 16. He pitched 11 for the Mets, three for the Reds and two for the White Sox. “Tom Terrific” proved successful opening the season, posting a 7-2 record. Steve Carlton started 14 of 15 openers for the Phillies from 1972 to 1986, missing only the 1976 tilt when Jim Kaat got the nod. Gaylord Perry holds the record for starting Opening Day games for five different teams. Perry toed the rubber to start the season for the Giants, Indians, Rangers, Padres and Mariners.

Walter Johnson may have been the most successful pitcher on Opening Day in baseball history. Johnson started 14 season openers for the Washington Senators, hurling a record seven shutouts. His overall Opening Day mark was 9-5, and his 14 starts were a record until bested by Seaver. Johnson’s two most famous Opening Day performances occurred in 1910 and 1926. On April 14, 1910, Johnson pitched a masterful one-hitter to defeat the A’s, 3-0. The only hit occurred in the seventh inning when Senators’ right fielder Doc Gessler tripped over a small child sitting on the edge of the warning track, allowing the ball to careen into the overflow crowd for a double. On April 13, 1926, Johnson made his 14th and final Opening Day start, battling 15 innings against Philadelphia’s Eddie Rommel, before winning 1-0.

The longest recent strings of consecutive Opening Day starts was eight, by Randy Johnson and Pedro Martinez. Johnson has started 13 openers in his career, six for the Mariners, six with Arizona, and one with the Yankees. Pitching for the Mariners in the 1994 opener at new Jacobs Field in Cleveland, with Feller watching from the stands, Johnson carried a no-hitter into the eighth inning before surrendering a hit.

Greg Maddux was a sure thing on Opening Day, with a perfect 6-0 record in seven career starts. Jimmy Key holds the record for most wins on Opening Day without a loss, with seven. Other perfect Opening Day hurlers: Wes Ferrell at 6-0, and Warneke and Rip Sewell both with 5-0 ledgers.

Home Run Feats on Opening Day

No batter ever hit as many home runs on Opening Day as Frank Robinson. The Hall of Fame outfielder and current Washington manager, belted eight career home runs on the first day of the season, while Willie Mays and Eddie Mathews each blasted seven Opening Day homers. Robinson’s final Opening Day homer, for Cleveland on April 8, 1975, came as a player/manager in his first at-bat in that role, as he became the first African-American manager in major league history. In addition to his record for most Opening Day homers, no other batter has equaled Robinson’s feat of hitting Opening Day homers for four different teams.

Only two batters have hit three homers in an opener. George Bell did so on April 4, 1988, when he hit all three of his home runs off Kansas City’s Bret Saberhagen. The second player was Karl “Tuffy” Rhodes, who launched three homers off Dwight Gooden of the Mets on April 4, 1994, in Wrigley Field. After Rhodes third homer, Cubs’ fans threw hats on the field, reminiscent of hockey fans homage to the hat trick. Tuffy’s shots made little difference – the Cubs still lost the game.

Team Records on Opening Day

Every fan would like to see his team get the season started with a “W,” but for St. Louis Browns fans it didn’t seem to indicate any future success. The record for most consecutive Opening Day wins by a team is nine, shared by the Browns, Cincinnati Reds and New York Mets. The hapless Browns, who captured just one pennant in their 52-year history, won every Opening Day tilt from 1937 to 1945, but finished with a winning record just twice during that span. The Mets matched that nine-year streak from 1975-1983, and the Reds put together their streak from 1983-1991.

Special mention goes to the Mets, who own the best winning percentage in Opening Day contests (27-17), despite losing the first eight openers in franchise history, from 1962-1969, by a combined score of 54-27.

Despite losing their 1969 opener, the “Amazin’ Mets” went on to win the World Series that season. Which begs the question: How often does a team that loses their Opening Day game go on to win the World Series title? Since 1903, 33 teams have lost their opener and still won the World Series, though the White Sox won their opener in 2005, 1-0 over Cleveland.

The record for most consecutive losses suffered in Opening Day games belongs to the Atlanta Braves, who lost every opener from 1972-1980, nine defeats in a row.

Managers will never admit that a win on Opening Day means anything more than a win in September, and several clubs have lost on Opening Day and still had successful seasons, but the one game can make a difference. A team that knows that first hand is the Red Sox. Four times the Red Sox have dropped their opener and finished the season one game out of first place. In 1948, the Red Sox lost a doubleheader opener to the A’s, then finished deadlocked with the Indians for the pennant before losing a one-game playoff. Boston also lost the 1949 opener and ended one game behind the Yankees; the Red Sox lost their 1972 opener to Detroit and finished one half-game back of those same Tigers for the division crown; and in 1978, Boston’s loss to the White Sox on Opening Day accounted for the difference between finishing one game ahead and tying the Yankees.

Snow Storms, Streakers and Parachutes

Some Opening Days have been marked by bizarre events, strange promotions, bad weather or a combination of all three. On April 11, 1907, the New York Giants opened the season in the Polo Grounds against the Phillies. The day before, a heavy snow had fallen and groundskeepers shoveled the snow into large piles in the outer reaches of the outfield and in foul territory. Late in the game, with the Giants trailing 3-0, the home crowd grew frustrated with the play of their team and began throwing snowballs onto the playing field, disrupting play. Soon, the situation grew chaotic as fans swarmed the field and pelted each other with snowballs, refusing to leave when confronted by police. Home plate umpire Bill Klem grew tired of the shenanigans once he was hit with a snowball, and forfeited the game to the Phillies.

On April 5, 1974, fans used different tactics to disrupt Opening Day in Chicago’s Comiskey Park. Several fans “streaked” onto the field, apparently having consumed too much alcohol. Numerous fights broke out in the stands before order was restored. “I never saw anything like it,” said White Sox manager Chuck Tanner. “If it goes beyond Opening Day, the average fan couldn’t take it.” There were no more reports of naked fans rushing onto the field in Chicago that season.

On April 11, 1912, Washington Park in Brooklyn was the scene of another Opening Day riot. With the home team down 18-3 to the rival Giants, fans began climbing the fences and running onto the playing field. Eventually, so many spectators infiltrated the diamond and slowed play, that the game was called on account of darkness in the sixth inning.

The Philadelphia Phillies earned a reputation for unique promotions for their home openers in the 1970s. At various openers, fans were thrilled by “Parachute Man,” who landed on the field prior to the first pitch; “Rocket Man,” who was propelled by a rocket pack over the playing field; “Kite Man,” who soared far above the stadium; “Cycle Man,” who roared over the artificial surface on a high-speed motor bike; and the “Great Merrifield,” an acrobat who performed stunts while suspended beneath a helicopter. On Opening Day in 1977, the Astros took their “shot” at contending with the Phillies, when they introduced “The Human Cannonball,” who was fired from a cannon at a reported 100 miles per hour into a nylon net.

Oakland owner Charlie Finley added his flair to the A’s 1970 opener when he used gold-colored bases on the field, something the commissioner’s office was quick to outlaw. Prior to the White Sox’ opener on April 9, 1976, owner Bill Veeck, manager Paul Richards, and longtime Veeck associate Rudy Schaffer dressed in Revolutionary War costumes and marched from center field to home plate as a fife and drum corps. Years earlier with the Cubs in 1961, Veeck had implemented one of his more famous stunts on Opening Day, when he employed midgets as vendors in Wrigley Field. Veeck figured the midgets wouldn’t block the view of the field as they sold their wares. It seemed like a good idea, however, Veeck didn’t plan for the fact that the beverage trays were very heavy, and by the middle innings, according to then Cubs’ broadcaster Jack Brickhouse, “The beer, soft drinks, and midgets were dropping all over the place.”

Opening Day stunts are not limited to the major leagues. The Little Falls Mets of the New York-Penn League planned to have four parachuters land on their field and deliver the first pitches of the season in 1982. Unfortunately, the pilot mistook a softball field for the baseball diamond and dropped his passengers ten miles from Little Falls. Meanwhile in Little Falls, more than 2,200 fans craned their necks searching for the men floating toward Veterans Memorial Park. The game started without them, and 20 minutes later they arrived at the park via car.

Occasionally, Opening Day catches a team off-guard. Sometimes the ballparks aren’t quite ready, but the game goes on. For their 1946 opener, the Boston Braves gave their outfield stands a fresh coat of red paint. But cold, damp weather prevented the paint from drying, and after the game, several hundred fans marched to the Braves’ offices to complain about the paint on their clothes. The team eventually agreed to pay all cleaning bills and placed a newspaper advertisement apologizing to fans. The Dodgers played their first game in Dodger Stadium on Opening Day in 1962. As fans poured in, team officials realized that the architects had forgotten to install drinking fountains. Several years earlier, in 1913, a more embarrassing situation occurred upon the opening of Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. Someone misplaced the keys to the bleachers, which resulted in thousands of fans milling about waiting to be seated.

Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn remembered that Opening Days were special for lots of reasons. “An opener is not like any other game,” he recalled in 1972. “there’s that little extra excitement, a faster beating of the heart. You have that anxiety to get off to a good start, for yourself and for the team. You know that when you win the first one, you can’t lose them all.”