An entertaining movie could be made about a trade that took place between the Pittsburgh Pirates and Oakland A’s on November 5, 1976. Yes, a baseball trade.

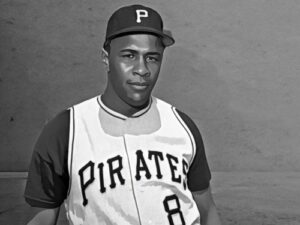

Well, the movie wouldn’t be only about the trade, but the trade would be the trigger in the plot. Let’s cast William Hurt as Charlie Finley, the colorful and cantankerous owner of the A’s. How about Will Smith as Willie “Pops” Stargell, and Idris Alba as “The Cobra,” Pirates slugger Dave Parker?

But the star would be J.K. Simmons, the wonderful character actor, who plays Chuck Tanner. Because Chuck Tanner was the biggest piece in one of the biggest, most important, and strangest trades in baseball history.

By the end of he 1975 season, Finley knew that baseball was changing forever. The economics of the game were flipping upside down: the power was shifting to the players. Free agency was making it difficult to make a buck in the game. Or so Charlie thought. The point is: Finley was done and he knew he future of the game didn’t include a tight-fisted maverick like him.

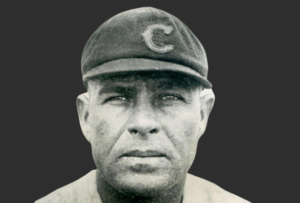

Just a few years earlier, Finley had the best team in baseball, winners of three consecutive titles, but entering 1976 the owner knew he needed new leadership as he watched his star players leave for more money. He lured Tanner from the White Sox to replace Alvin Dark in the manager’s office. It marked a signal change because Tanner was a fearless innovator and a genius at coaxing the best effort out of his players.

At spring training in 1976, Tanner stood in front of his team and gave them a directive: run. Yes, run. Run, run, run. In the first inning, in the ninth inning, when you’re ahead and when you’re behind. Just run.

In ’76, the A’s stole 341 bases, a league record. The fast guys stole bases (Bert Campaneris stole 54 and Billy North swiped 75), and the not-so-fast guys stole bases too (Sal Bando stole 20, and Don Baylor pilfered 52). But even non-players stole bases: Matt Alexander and Larry Lintz, who combined for only 34 plate appearances, stole a total of 51 bases. They were professional pinch-runners, and they scored 37 runs for Tanner’s team.

The A’s managed to win 87 games in 1976, but Finley didn’t care, he wanted to dismantle the club. In November he got a call from Pittsburgh general manager Hardy Peterson, who may have sounded like a law firm, but was actually a flesh-and-blood baseball man. Peterson wanted a new manager for his team, which had just lost veteran skipper Danny Murtaugh, who retired after a long career in the dugout.

The Pirates were one of the most successful teams in baseball in the 1970s, winners of division titles in five of the six seasons between 1970 and 1975. But they needed a new voice in the clubhouse, which was dominated by strong personalities.

Peterson made a unique request: he wanted Finley to allow Tanner to get out of his contract with Oakland so the Pirates could negotiate with him. Finley knew a live one when he saw one, and he fed Peterson’s interest.

“Chuck will be great for your team,” Finley told Peterson. “You won’t find a better man for the job.”

But Charlie wanted something special for Tanner’s rights. “Give me a player,” Finley demanded. “I want a front line player, because I’ll be handing you the pennant.”

Peterson came up with an idea. He had a young catcher named Ed Ott who needed to get into the lineup. But the team had veteran Manny Sanguillen behind the plate, a career .303 hitter. Sanguillen was 32 years old and was never a great defender behind the mask. Ott would be a defensive upgrade, and the pitching staff preferred pitching to him.

“I’ll give you Sanguillen for Tanner,” Peterson said.

“Throw in $200,000 and you got a deal,” Finley countered. The two sides eventually agreed on $100,000 in cash to sweeten the transaction. The deal was only the second trade in baseball history that involved a manager. The first came in 1960 when the Indians dealt manager Joe Gordon to Detroit for manager Jimmy Dykes.

What did Chuck Tanner mean to Pittsburgh? First, he was coming home: Tanner was born in New Castle, a suburban community located north of Pittsburgh. Second, baseball has never seen a more optimistic skipper than Tanner.

“He’s an optimist’s optimist,” The Sporting News wrote in March of 1977. “He always looks to the brighter side of things. He turned a losing White Sox club into a respectable team. He worked one year in Oakland for Charlie Finley and he doesn’t publicly knock Finley.”

Tanner understood what legendary basketball coach John Wooden said about building a team: “infuse positive thinking and be more interested in character than reputation.” Tanner had the gift to be able to see the best qualities in each of his players.

The Pirates adopted Tanner’s speed game too: in 1977 they swiped 260 bases. All that movement led to runs and the runs led to wins. The Bucs improved to 96 wins in 1977 in their first season under Sunny Chuck.

Two years later, Tanner (and Ed Ott and ironically Sanguillen, who had been reacquired from the A’s), spun all that positive energy into a special season. By that time, Stargell, one of baseball’s greatest sluggers, was handing out stars for each big contribution to a team success. The Pirates, with their bright polyester yellow and black uniforms, topped by old school pillbox caps (festooned with stars) were baseball’s biggest story.

With Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family” blaring in the clubhouse after Game Seven of the 1979 World Series, Tanner found himself in a bear hug from superstar Parker.

“I love you Chuck!”, Parker yelled as he lifted the skipper off his feet amidst the champagne and celebration.

“This is the greatest day of my life,” Tanner said. “God bless Charlie Finley!”