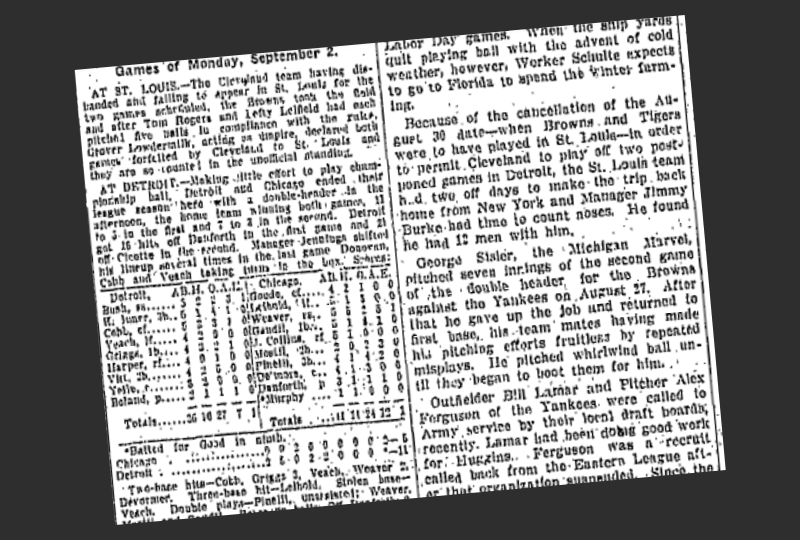

When fans settled into Navin Field for the traditional Labor Day doubleheader in 1918, they had no idea that they would see a 41-year old coach pitch, and that a pharmacist would play the outfield in place of Ty Cobb. But that’s what happened.

Shortened Season Due to World War

On September 2, 1918, the baseball season was coming to a premature end due to the war in Europe, which resulted in the “Work or Fight” edict. Because professional baseball was not considered an essential industry, most professional ballplayers had jobs in war factories awaiting them, or were prepared to report for military duty. With the pennant races decided, the Labor Day doubleheaders were meaningless in the standings. Nevertheless, as the Detroit News reported, “Some 8,000 real fans assisted in the burial of base ball at Navin Field… and not one of them went home disappointed.”

The fans were treated to a rare spectacle prior to the first game, when dozens of “aeroplanes,” as they were described by the Detroit Free Press, crisscrossed the skies above Navin Field, dropping patriotic literature.

Following the high-flying performance, game one proved to be a typical baseball battle, with Detroit defeating the visiting Chicago White Sox, 11-5. Tiger manager Hughie Jennings used a standard lineup in that contest, but events during the intermission led to a different approach in game two.

Former Tiger Attended Season Finale in Detroit

Former Tiger pitcher Bill Donovan, who twice won 25 games in a season, was serving as a coach for Jennings at that time. Spectator Davy Jones, himself a former member of the Tigers, who had retired three years earlier, strolled over to the Detroit bench to meet with his former mates. Having settled in Detroit, Jones was one of the most successful pharmacists in the city. Years later in an interview with author Lawrence Ritter, Jones described the events of that day:

“I went over to the Detroit bench to say hello. The crowd was hollering for Bill Donovan to pitch the second game. So Bill turned to me and said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll go out and pitch if you play left field.’ Jennings said ’sure, that’d be fine,’ and he turns to one of the players and said ‘go in and take off your uniform and give it to Davy.’”

Nestled atop his familiar perch on the pitchers mound, Donovan displayed no signs of rust, despite the fact that he hadn’t pitched regularly in seven seasons. The right-hander twirled five innings, allowing just one run to the White Sox. In the sixth inning, Jennings shuffled his lineup: replacing Donovan with Ty Cobb; shifting catcher Oscar Stanage to shortstop; and inserting retired-ballplayer-turned pharmacist Jones into center field. After two innings with that lineup, Jennings waved left fielder Bobby Veach to the mound and moved Jones to left. Finally, after further encouragement from the crowd, the Tiger manager grabbed a glove and played third base. The 49-year old Jennings, who had starred as a shortstop in the 1890s, handled two chances flawlessly in the field, much to the delight of the Detroit faithful, who welcomed the farcical diversion from the headlines dominated by war.

Details of Game Were Misreported for Decades

Ironically it was Jones who recorded the last putout of the game, gathering in a flyball to secure the final out of the 186th – and final – victory of Donovan’s career. The baseball, which Jones kept, ended up in the Baseball Hall of Fame collection and helped change the official statistics of major league baseball nearly 90 years after that game.

For years, Jones told the story of that game. The baseball he caught for the last out was one of his favorite possessions from his playing career. The ball, which Jones donated to the Hall of Fame in 1955, bears the hand-written inscription: “Last ball used in game at Navin Field in last game of season, 1918, caught by Davy Jones. Hit by Jack Collins of Chicago White Sox. Season ending on Labor Day on account of War.”

But for nearly 90 years an oversight kept Jones, who passed away in 1972, from receiving the credit for his part in that 1918 game.

In 1918, the official scorer had marked “D. Jones” in the score sheet and sent it off to the league offices. The officials in the league office assumed that the “D. Jones” was Deacon Jones, a Tiger relief pitcher. Donovan and Jennings both received credit for their appearances in the game, but Davy Jones did not, and Deacon Jones was mistakenly given credit for Davy’s performance.

Confronted with the facts of this story, as well as the baseball from the Museum’s collection, the Elias Sports Bureau, official statisticians of major league baseball, will soon add the game and two putouts to the playing career of Davy Jones, who attended that Labor Day game as a pharmacist and former ballplayer, but ended up catching the last out of the last game before baseball went to war.