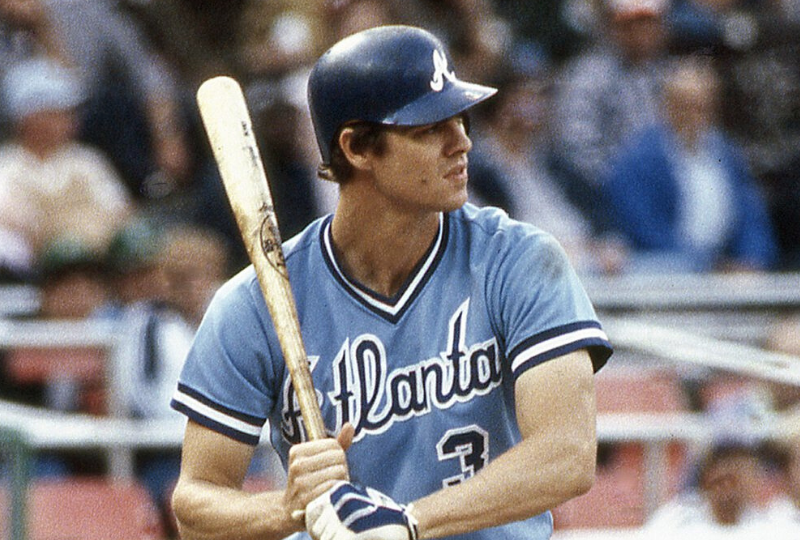

Before a game during the 1983 season, Dale Murphy visited with a six-year old girl who had lost her hands and a leg when she stepped on a downed power line. The girl and her family were huge Atlanta Braves fans and her caregiver asked Murphy if he could hit a home run that day for her. Murphy mumbled embarrassingly and agreed with a nod, knowing it was not something he should guarantee. But in his second trip to the plate that afternoon, Murphy sent a pitch into the left field stands for a two-run homer. If that weren’t enough, in the sixth inning, Murphy hit another home run, this one even deeper. The Braves won the game 3-2 and the Murphy legend grew even larger.

Dale Murphy was an anomaly: a superstar who was humble, quiet, embarrassed by publicity. He was gracious in victory and defeat, and he never ever had anything bad to say to anyone on a baseball field. In an era when superstars were demanding millions of dollars and special treatment, Murphy was a breath of fresh air. In fact, he was almost a freak.

“If you’re a coach, you want him as a player,” said Joe Torre, who managed Murphy in Atlanta for three seasons. “If you’re a father, you want him as a son. If you’re a woman, you want him as a husband. If you’re a kid, you want him as a father. What else can you say about the guy?”

In the clubhouse Murphy stood out. He refused to do interviews unless he was fully dressed. He refused to pose for photos with female fans who were touching him or scantily clad. When he went to dinner with his teammates he was happy to pick up the check – as long as there was no alcohol on the tab. A clean liver, Murphy shunned swearing, tobacco, alcohol, drugs, and any other vices that ballplayers usually swarmed to. He may have stood out among his teammates because of it, but his performance on the field made him another one of the guys – albeit a superstar.

From 1982-87, Murphy was the best player in baseball. Over those six seasons, the Atlanta center fielder averaged 36 homers, 105 RBI, 110 runs, and 18 stolen bases. In 1982 and 1983 he was named Most Valuable Player, leading the league in runs driven in both seasons. He could hit the baseball remarkably well, but Murphy was also a great baserunner and fielder: he won five consecutive Gold Gloves.

“He ‘s the most consistent and sure-handed outfielder I’ve seen since Willie Mays,” Montreal manager Bill Virdon said.

Murphy swiped 30 bases in 1983, becoming the first Brave to reach 30 in homers and steals in the same season. Batting third in the lineup, Murphy was a dangerous nemesis for opposing pitchers day-in-and-day-out: he played in 740 consecutive games from 1981 to 1986.

Playing for a team that televised every one of their games in cable television (Braves and WTBS out of Atlanta), Murphy drew a fan following well outside Georgia. His clean-cut image endeared him to fans of all ages. But in 1990 the 34-year old was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in the middle of the season, a deal that shocked and enraged fans of the team. When he faced reporters following the transaction, Murphy had tears in his eyes.

He never played as well after leaving the Braves, and when the Phils released him during spring training in 1993, the humble veteran took a $2 million pay cut to sign with the expansion Colorado Rockies. He retired after that season and held two press conferences to announce his decision: one in Denver, the other in Atlanta. He would always consider himself a Brave.

Murphy received enough votes to keep his name on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot for 15 years, the maximum allowed, but his candidacy never gained much traction with the writers for some reason. For a stretch of 5-10 years, Murphy was unquestionably the best all-around player in the National League and one of the best in the game. He led the league in five different important offensive categories and he garnered MVP votes in seven seasons. In fact it’s his MVP consideration that is probably his best case for the Hall of Fame: in addition to winning two MVP awards outright, Murph was 7th once, 9th once, and in the top 12 a total of six times.

Should Murphy be in the Hall of Fame? Where should he rate among the great center fielders in baseball history?

Much of Murphy’s value came within the ten-year period from 1978 to 1987. That’s not unusual: most players great and small, have a concentrated stretch where they are the most valuable. Only the greatest of the greats can sustain that for more than a decade. Even a decade is a long stretch. At any rate, over that ten-year period, Murphy had about 42 WAR. (I use WAR because it’s an accurate snapshot of player value across baseball history. And when you compare WAR to other “more traditional” stats like OPS or it’s components on-base percentage and slugging, or runs, RBIs, and total bases, it still rates most of the same players who we think are great as great, and so on). His WAR total ranked 17th in baseball from 1978 to 1987. He rated behind legends like Mike Schmidt and George Brett and Gary Carter, also Robin Yount. Rickey Henderson also ranked ahead of Murphy, as did center fielder Andrew Dawson, almost an exact contemporary. But in addition to those two outfielders, Murphy’s WAR total ranked beneath that of two other outfielders: Chet Lemon and Dwight Evans.

That’s why his status as a Hall of Famer and all-time great is on shaky ground. Henderson and Dawson are transcendent players. But Lemon and Evans, while they were very good, neither is in the Hall of Fame, and neither are particularly top candidates. Marginal candidates yes, but based on the numbers neither Lemon nor Evans will likely ever get a Hall of Fame plaque.

Our list of the Top 100 Center Fielders of All-Time has Lemon at #18 and Murphy at #25. A few of the center fielders we have ahead of Murphy are Kenny Lofton (#9), Carlos Beltran (#10), and Jim Edmonds (#14). Then there’s #24 Fred Lynn (a peak candidate) and #26 Johnny Damon (a career value candidate), but there’s also Jim Wynn (#16) and Willie Davis (#15), two excellent center fielders that very few are arguing as Hall of Famers.

Regardless of how our ratings see Murphy, the former two-time MVP has his share of supporters.

“I can’t imagine that Joe DiMaggio was a better all-around player than Dale Murphy,” Nolan Ryan said.