This is the first in a ten-part series looking at the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Pre-Integration Era Ballot.

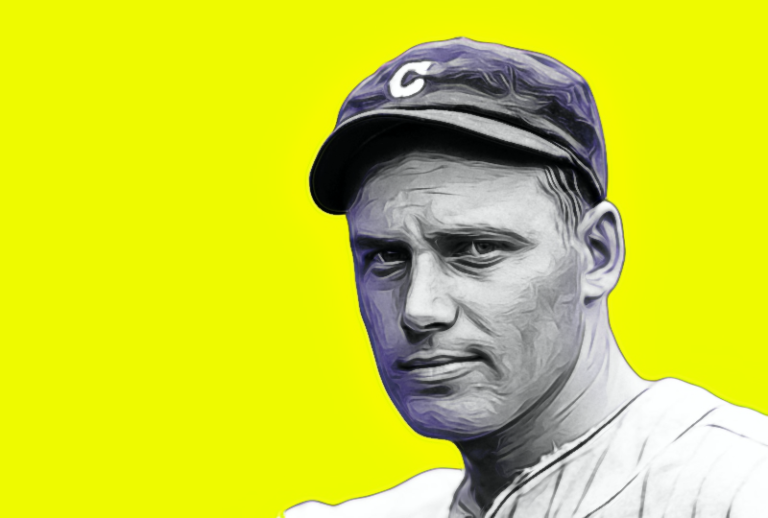

When he was at his peak, Wes Ferrell was one of the best right-handed pitchers in the game, and there was never any doubt that he was a better player than his brother Rick, a catcher. Ironically, Rick ended up in the Hall of Fame, while Wes has been assigned to that fairly anonymous group of players known as the “best players not in the Hall of Fame.”

But even though Was threw his last fastball before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and even though he died more than four decades ago, Ferrell continues to garner support for Cooperstown. That’s a testament to his statistical achievements, and also to his strong personality. Unfortunately, it may have been that personality that kept Wes from the Hall while he was alive when baseball writers had a flesh-and-blood reminder of his cool treatment of them. Now, it’s only his exploits on the diamond that keep his name alive for consideration, and rightfully so.

In the 1930s, Ferrell led all pitchers in complete games: he was a workhorse, similar to Jack Morris. And, like Morris, Ferrell did it in a hitter’s era where he didn’t always post a low ERA. Ferrell had an ERA of 4.08 in the decade, and 4.04 for his career, but he was a winner (again, like Morris). Ferrell won 170 games in the ’30s, a figure surpassed only by Lefty Grove, Carl Hubbell, and Red Ruffing. All three of those pitchers are in the Hall of Fame, the first two because they were outstanding, the latter because he was pretty good for a team that won a hell of a lot.

Ferrell, on the other hand, toiled mostly for losing teams (there the comparison with Morris ceases). His first seven seasons were spent with the mediocre Cleveland Indians, then he spent parts of four seasons with the Boston Red Sox, who had a winning percentage below .500 despite Ferrell and Grove being in their rotation during the Great Depression.

It was in The Hub where Ferrell’s famous temper got him into trouble. During a game against the Yankees on August 21, 1936, Ferrell stormed off the mound after a fly ball fell between two of his outfielders. He brushed aside manager Joe Cronin and teammates and retreated to the clubhouse. Earlier in the season, the strong right-hander made an obscene gesture at Fenway Park fans after surrendering a few runs, and on another occasion he argued with Cronin from the mound when he saw a relief pitcher warming up in the bullpen. Ferrell’s red-hot personality reared its head often during his career. In the parlance of the times, he was known as a “red-ass.”

For leaving the mound during that game, the Red Sox fined Ferrell $1,000, the highest disciplinary fine of that sort since the Yankees walloped Babe Ruth after he reportedly hung manager Miller Huggins off the back of a moving train. A 25-game winner in 1935 for the Red Sox, Ferrell threatened to take legal action in the face of the fine, but he finally backed down and returned to his team, though he was hardly welcomed with open arms by Cronin and his teammates who supported their manager. Still, Ferrell showed his competitive fire by winning his next start, a five-hit shutout of the Tigers. He won four of his next five starts and finished the year with 20 wins. It was however, his final full season in a Boston uniform. Just 29 years old as the next season began, and with more than 160 victories under his belt, Ferrell still seemed like he could rack up another 100+ wins as he entered his 30s as a seasoned hurler. Instead, he struggled in Boston in ’37 and was exiled to the Washington Senators where he suffered his most serious arm injury. Brief stints with the Yankees, Brooklyn Dodgers, and Boston Braves followed, but Ferrell never regained his dominant form.

Despite the arm injury that limited him to just 18 wins in his 30s, Ferrell did a lot of eye-popping things in his career: he won 20 games six times, led the AL in complete games four times, in innings three times, and in wins once. When he was healthy, he was a pitcher who could be counted on to take the ball 35-40 times per season and keep his team in the game. He had an excellent fastball, very good curve, and a great changeup, but after arm injuries robbed him of his velocity, he mostly got opposing batters to pound the ball into the ground. He was a contact pitcher who actually walked more batters than he struck out.

One other thing worth mentioning in regards to Ferrell’s case for the Hall of Fame: he was the best hitting pitcher in baseball. He may have been the best hitting pitcher to ever play the game (excluding the likes of Babe Ruth and George Sisler, who went on to be position players). Ferrell hit .280 over the course of his 15-year career, and his 38 homers are more than his brother Rick hit as a catcher. In fact the 37 homers that Wes hit as a pitcher are the most in baseball history at the position. He was dangerous with a bat in his hands, and even after his big league career was over due to an arm injury, he was hitting well over .350 with power as a minor league player/manager who spent time in the outfield. Wes also had a keen eye at the plate: he posted a .351 OBP to go with his career SLG mark of .446 in the big leagues.

Despite his impressive credentials as a pitcher and his fantastic record with the lumber, there’s no overlooking the fact that Ferrell posted a 4.04 ERA (which would be the highest ever for a Hall of Famer) and he was finished as an effective pitcher at the age of 30. Ferrell won 190 games through the age of 30 and only three after it. Had there been modern surgical techniques in his time, Ferrell most likely could have pitched regularly for many more seasons. But sports medicine was fairly rudimentary in the 1930s and Ferrell’s “tired arm” forced him to retire after the 1941 season. It’s most likely that he suffered a torn elbow ligament, something they wouldn’t have been able to diagnose in that era.

Ferrell’s name continues to crop up on the Hall of Fame old-timers type ballots because he won 20 games six times and did it for teams that were mediocre to average. He won 60% of his decisions despite pitching for teams that won about 51% of the time when he wasn’t on the mound. Ferrell threw a no-hitter and was a member of the very first American League All-Star team in 1933. He won 20 games when he was 21, 22, 23, and 24 years old. His 4.04 ERA is also not as bad as it seems, since the league average during his prime was about 4.75, and he ranked in the top ten in his league in the category seven times in an eight-year stretch from 1929-1936. If you want to view his accomplishments through the scope of modern advanced statistical analysis, note that he ranked second in WAR among pitchers four times.

Circumstances beyond his control have also worked against Ferrell’s legacy. Had he pitched for the Yankees in his prime (like Ruffing and Lefty Gomez), Ferrell may have been inducted years ago, but he was relegated to so-so teams where his crusty personality rubbed his managers, the front office, and his teammates the wrong way. He never got to toe the rubber in a post-season game.

It’s fashionable to point out that Ferrell was probably a better player (and ironically a better hitter) than his brother, who has a plaque hanging on the wall in Cooperstown. But that’s more of an indictment of Rick’s election than it is an argument for Wes to be in the Hall of Fame.

In my opinion, the incomplete career is not enough to make Wes Ferrell a Hall of Famer. It’s not like he put up Sandy Koufax numbers before his arm injury. Ferrell was very good for a short time, then his arm wore out and he was done.

If the HOF’s special committee subscribes to the small-Hall theory, Ferrell has no right being elected. However, if they want to embrace the “If he’s in, this guy should be in” view of the Hall, then Ferrell should get serious consideration. There’s no evidence to suggest that Ruffing or Herb Pennock were better pitchers than Ferrell. Ditto Catfish Hunter, who had an adjusted ERA of 104 to Ferrell’s 116, and who like Ferrell succumbed to an arm injury in his early 30s. Hunter had the fortune to pitch and win 20 games for a lot for winning teams, so that’s the only real difference between he and Wes. Ferrell was probably better than Catfish, but he deserves a plaque only if you believe every player who’s better than the lowest rung of Hall of Famer deserves to be enshrined.