This is the second in a ten-part series looking at the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Pre-Integration Era Ballot.

There are currently nine umpires enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, a perfect baseball number. But with his name on the HOF’s Pre-Integration Ballot, Hank O’Day is now a step closer to becoming the tenth.

Three of the umpires were elected in the last 20 years: Bill McGowan, Nestor Chylak, and Doug Harvey. We can argue the merits of inducting umpires into the Hall, but that’s another article. Let’s just say that no one makes a pilgrimage to Cooperstown to see an umpire inducted into the Hall of Fame or to look at an umpire exhibit. Except maybe the family of the honored umpires.

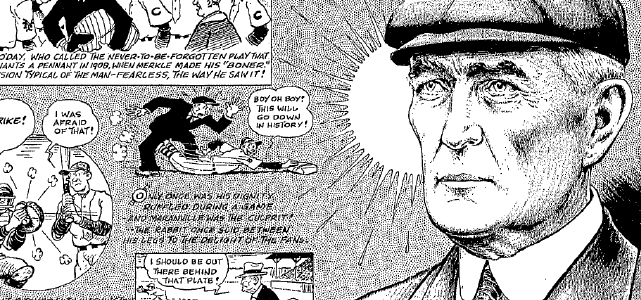

Baseball’s bible, The Sporting News, once called O’Day “sphinx-like, fearless, and honest.” That was in 1935 after his death, but had they written about him today, when warts are more visible through the prism of the media, they may have called him “crotchety, cocky, and cocksure.” O’Day was all of those things. But he was also a unique figure in baseball history.

O’Day is the only man to regularly pitch, manage, and umpire in the major leagues. While most arbiters gravitate to umpiring because they cannot play the game well enough to make The Show, O’Day began his career as a pitcher and advanced all the way to the majors.

Born in Chicago during the U.S. Civil War, O’Day made his professional baseball debut with Toledo in 1884. He was a tall (6 foot at that time was pretty tall), right-handed pitcher, though never a great one. In his best season he won 22 games in the Players’ League as he dominated lesser competition in that short-lived league in 1890. Otherwise, O’Day was a mediocre hurler who also spent time in the outfield between starts. But during his playing career he earned respect in a few trials as a fill-in umpire, and in 1895 the National League hired him full-time to officiate games.

O’Day earned a reputation as being excellent at calling balls and strikes, and like a few other good umpires in history (Bill Klem, for example), O’Day spent most of his time behind the plate in the two-man crews of that era.

He worked the very first modern World Series in 1903, and umpired in eight more (possibly nine, depending on your source), a total eclipsed by only two other umpires when he retired in 1927.

Over the course of his career, O’Day gained a reputation for being ornery and aloof. Most accounts of him included the words “mystery” and “steely-faced.” O’Day was one of those guys who took almost everything seriously. He wasn’t a guy who cracked jokes or engaged in chit-chat. He was a product of a the mid-19th century and he was intolerant of anything that was not civil and purposeful. It was that approach that served him so well as an umpire – to O’Day the rules and traditions of the game were everything.

It was his adherence to the baseball code that put O’Day at the center of the most controversial call in baseball history. On September 23, 1908, in a game between the Cubs and Giants at The Polo Grounds in New York, Al Bridwell’s single scooted into center field to drive in what seemed to be the winning run for the home team. As most of the Cub players left the field and the Giants celebrated, O’Day stood at his position behind the plate. A Cubs player asked base umpire Bob Emslie if the Giant runner on first base, Fred Merkle, had touched second. Emslie responded that he had not. As a result, a force play was still in order at second, and when the Cubs tossed a baseball to second baseman Johnny Evers and he stomped on second, Emslie ruled Merkle out. As the crew chief, Hank ruled that the run that scored from third base did not count as a result of the force, which is by rule the case. At that time, however, the common practice in baseball was that runners frequently did not touch the next base even though the rule book required them to do so to eliminate the force. O’Day’s ruling was a strict enforcement of the rule book. The Giants cried foul, with the loudest voice coming from their manager John McGraw. The NL offices supported O’Day’s ruling to suspend the game due to darkness. A replay of the game would need to be played if it was necessary. Ironically, it proved necessary, as the Giants and Cubs ended in a virtual tie atop the standings. When the game was replayed at the end of the season, the Cubs won. McGraw argued for years that O’Day had robbed him a pennant in 1908. Merkle was forever stamped with the inglorious nickname “Bonehead” for his failure on the base paths. The game and the controversial call remain in baseball lore.

Because of his knowledge of the rule book and courage to make tough decisions, O’Day was well-respected by most baseball officials. In 1912, Cincinnati owner August Hermann hired O’Day to be the manager of the Reds. Hermann was one of the most influential owners in the National League at the time, and had been the one of the people who urged NL President Harry Pulliam to back O’Day’s ruling on the ’08 Merkle play. In Cincinnati, O’Day traded his balls-and-strikes counter for a lineup card, taking over the reins in the dugout. Though he lasted just one season in Cincy, Hank improved the team’s record by five games and inched them up two notches in the standings. After Hermann hired a new skipper for the 1913 season, O’Day was welcomed back to the umpiring ranks by the Senior Circuit. Two years later he was back on the sidelines as manager of his hometown Chicago Cubs, a team in disarray after selling off most of their stars. The Cubs posted a winning record and finished 4th in the one season with O’Day at the helm. The following year he was back in the blue suit as an umpire for the National League. It seems no one ever questioned that O’Day may have a conflict of interest in returning as an umpire in a league with two teams he had previously managed. Such was the level of integrity he earned by those who knew his work.

After his last managerial job, O’Day spent another 13 seasons in the league as an umpire, solidifying his spot as one of the most senior members of the league. He did not wish to retire after the ’27 season at the age of 65, but the NL forced him into a role as “umpiring supervisor and scout”, which he bristled at. He spent the last few years of his life in and around his native Chicago before passing in 1935.

A story from his career illustrates how serious of a man Hank was. In a game between the Boston Braves and New York Giants at The Polo grounds in 1919, O’Day was stationed on the bases. Speedy Boston shortstop Rabbit Maranville was on first base when he bolted toward second on a stolen base attempt. O’Day pivoted and ran a few steps to second to witness the play, but Maranville slid head first to the inside of the bag and went right through Hank’s legs and wrapped his arms around second base. Maranville, a flashy player who never missed an opportunity to promote himself on the diamond, stood up and doffed his cap to the crowd, who had never seen such an odd arrival at any station on the diamond. Reportedly, O’Day leafed quickly through the rule book, and finding nothing that prohibited a runner from doing such a thing, ruled Rabbit safe – always the stickler for the letter of the law.

When O’Day retired his total of 3,986 games were third all-time for umpires. His total of 2,710 games behind the plate still rate second to Klem all-time. Based on his reputation, selection for World Series games, longevity, and unique careers as a player and manager, O’Day would be a solid addition to the short list of umpires honored in the Hall of Fame.