This is the fourth in a ten-part series looking at the Baseball Hall of Fame’s Pre-Integration Era Ballot.

If it hadn’t been for a sense of loyalty to one of his best friends in high school, Marty Marion probably never would have went to an open tryout held by the St. Louis Cardinals. And if it hadn’t been for that same friend being signed to a minor league deal, the 17-year old Marion probably never would have penned his name on a contract. If neither of those things happen, we aren’t discussing the Hall of Fame merits of Marion, who went on to star for the Cardinals in the 1940s.

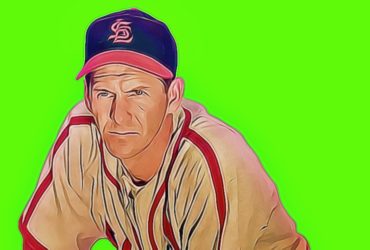

Marion never looked like a shortstop – he was tall and skinny with bony elbows and knees. He looked like the guy who should be counting the ticket sales, not the guy who was responsible for fielding hard-hit grounders in the middle of the diamond. For most of baseball history, shortstops had been small men who scooted around the infield. In fact Scooter and Pee Wee and Rabbit were names given to famous shortstops in that mold. But Marion was one of the first of a new breed of shortstops who emerged in the late 1930s and 1940s. Though he looked like he wouldn’t be a good fit for the position, in fact he developed into the best defensive shortstop of his era.

“When I was one the mound with Marty behind me,” Cardinals pitcher Murry Dickson said, ” I knew that if the ball was hit on the ground to my right, he was going to get his glove on it.”

Gold Gloves were not awarded in Marion’s time, but had they been he surely would have won at least seven or eight of them. He was excellent with the leather. But he had to be coaxed into signing that first contract in 1936. After being spotted at the tryout by the Cardinals scouts, he was offered a deal based on his stellar play in the field, but Marty didn’t want to forego his college plans. Marion’s goal was to be a mechanical draftsman. But when his high school teammate inked a contract, Marty was convinced that he too might want to give the National Pastime a whirl. Within four years he was starting at short for the Redbirds and earning rave reviews around the National League.

“The guy isn’t human,” Pirates manager Frankie Frisch complained. “You just can’t get anything by him.”

Perhaps Marion wasn’t human – one of the nicknames his teammates bestowed upon him was “The Octopus” due to his long reach and the way he seemed to have eight arms while gobbling up groundballs. Marty was also dubbed “Slats” due to his wiry, pencil-thin, 6’2, 175-pound frame. But the nickname that was he most coveted was simply, “Mr. Shortstop,” which summed up his brilliance at the position.

Due to that excellence in the field, Marion has another shot at the Hall of Fame (he’s appeared on the ballot before), but this time he may have as strong a case as he’s ever had. Modern statistical analysis continues to shine a light on the importance of defensive play, and Marion stands out among players at his position, as Bill Mazeroski did at second and Ozzie Smith did at shortstop. Both Maz and the Wizard of Oz are in the Hall of Fame based almost solely on their defensive ability, and if Marty is to earn a plaque in Cooperstown that will also have to be the route he takes.

Marion was never a very good hitter – in fact he was well below average during his career. He once led the NL in doubles and he paced the league in sacrifice hits twice, but besides that he never sniffed the air of the league leaders with the stick. He was a low-average hitter who didn’t walk much and only hit 36 homers in his entire 13-year career – or about 4-5 months worth for a slugger. He was a #8 or #7 hitter his entire career, even in 1944 when he won the NL Most Valuable Player Award while hitting .267 with 34 extra-base hits and 63 RBI. That season his team won the pennant.

Like many other shortstops of his era who played on winning clubs, Marion received MVP consideration nearly every season. Back then, the importance of a shortstop was seen as critical to success. Shortstops could hit .250-270 with 5-10 homers and finish high in MVP tallying if they were considered good with the glove and their team won (it happened every year). Marion received MVP votes in seven of his 11 full seasons. He was named to seven All-Star teams.

The Cardinals won four pennants in a five-year stretch with Marion in the middle of the infield. They were the best team in baseball during the World War II years, and Marion was one of their stars. He performed pretty well in the World Series, driving in 11 runs in 23 games and batting .357 in his only loss in the Fall Classic, in 1943.

After the 1950 season, in which he hit .247 in 106 games, the 32-year old Marion was asked to manage the Cardinals, taking over for Eddie Dyer. In ’51, Marion did not play, guiding the Redbirds to a 3rd place finish as he concentrated solely on his managerial duties. But despite the one-year audition, the Cardinals released him in October. The crosstown Browns snagged him as their played manager for the next two seasons, though Marion wrote his own name into the lineup sparingly. The job was mostly extended as a publicity stunt, and after losing 100 games in ’53, Marion was fired by the Browns. His career was over.

Thus, for a player known for his defensive skill, Marion had a brief career. He was finished as an everyday player at the age of 32, and he played in a total of only 1,572 games. Yes, he was a great defensive player, but his offensive numbers were meager.

Based on his short career and the weak hitting stats on his ledger, Marion is a stretch (no pun intended) for the Hall of Fame. When stacked up against the contemporary shortstops who are in the HOF (Lou Boudreau, Pee Wee Reese, and Phil Rizzuto), Marion is their superior with the glove, no question. At the plate he ranks well below them, however. One might compare him to Mazeroski, a second baseman who earned election solely because he was great in the field, but Maz played more than 2,000 games and collected more than 2,000 hits. They were similar players in offensive quality (Marion walked more and Maz had more power but essentially they were each about 20% below league average at the plate), but Maz stuck around much longer. If Marion’s defensive play was valued that much, why did he stop playing at the age of 32? Surely some club could have used his All-Star glove?

The only way Marion deserves to be elected to the Hall is if the committee determines that the 1940s are under-represented at the shortstop position – that three Hall of Fame shortstops who played the bulk of their careers in that era is not enough. But if that’s the case, then Vern Stephens and Cecil Travis are more compelling alternatives.