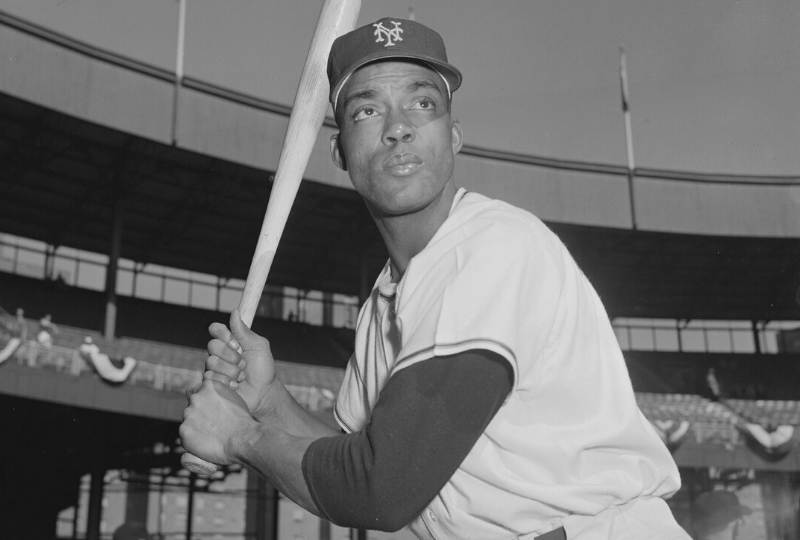

Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, a fantastic baseball player and a great all-around athlete, has passed away at the age of 96.

Irvin overcame many career obstacles to garner the acclaim he deserved as a baseball player. He toiled for nearly a decade in the negro leagues, missed three of his prime years while serving in World War II, and battled the prejudices of integration in the major leagues. Still, he eventually earned election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, nearly 20 years after playing his final game. He lived more than four decades after that, spreading his love for the game of baseball as a popular ambassador of the National Pastime.

Montford Merrill Irvin was born on February 25, 1919, in Haleburg, Alabama, but he grew up in New Jersey. As a teenager, Irvin was a star in four sports: football, basketball, track, and baseball. He set a New Jersey state record for throwing the javelin, was a great triple jumper, and he was offered scholarships to play college football. But Irvin was lured by the promise of playing professional baseball in the negro leagues, the only option for an african-american in the 1930s. He was signed by the Newark Eagles, where he was a favorite of owner Effa Manley, a rare female in a power position in sports in that era, and herself a future Hall of Famer.

Irvin was an immediate standout for Newark in the negro leagues, hitting for a high average and displaying good power. He was a fast outfielder who played left field and center field depending on the needs of the team. Though statistics were sketchy for that league, Irvin was a strong right-handed hitter who batted over .300 on an annual basis.

“Monte was the best athlete on our team and he could have starred anywhere on the diamond,” said teammate Larry Doby, who played center field with Irvin with the Eagles.

From 1942 to 1945, Irvin was in the U.S. Army and missed almost four years of his prime. Unfortunately, at that time a few owners in the big leagues were making secret plans to integrate, and Irvin was one of the players who was targeted to be the first black player. But his time missed in the military and some contract squabbles after that scared Branch Rickey away. Instead, Jackie Robinson integrated the major leagues in 1947. Irvin, a five-time negro leagues All-Star, was a coveted player after Robinson made it clear that african-americans were going to make a big impact in MLB. In 1949 the New York Giants signed Irvin, in large part to compete with Brooklyn, who was attracting many of the african-american fans in the city. In July of 1949, Irvin made his debut, but he struggled in his first year in the major leagues.

In 1950, at 31 years of age, Irvin showed his talent by hitting .299 for the Giants with 15 homers. He was even better the following year as the Giants won the pennant, finishing third in MVP voting on the strength of 24 homers, 121 RBI, a .312 average and a .415 on-base percentage. For his career, Irvin was a patient hitter who was tough to strike out, he walked 351 times and only fanned 220 times in eight major league seasons. Irvin was an All-Star in 1952 and he gained MVP votes in three separate seasons. He was released by the Giants when he was 36 after struggling in 1955 and latched on with the Cubs for one final season. His major league stats show a .293 batting mark and a very good OBP of .383 and slugging percentage of .475. He averaged 21 homers a season and nearly 100 RBIs. But his numbers didn’t show the full measure of the ballplayer: he had missed his age 19 to 29 seasons due to segregation and the war. It’s likely that Irvin could have accumulated more than 2,500 hits, 300 homers, and 1,200 RBIs if he had been able to play uninterrupted.

The Hall of Fame, to its credit, recognized Irvin’s greatness and he was finally honored with election in 1973 by a special negro leagues’ committee. Satchel Paige, who had played with and against Irvin, said of him: “Monte hit balls that just seemed to keep rising and rising until they went over [the heads] of the outfielders.”

Irvin held several jobs in baseball after his playing career ended, he was a champion of the Negro Leagues Museum in Kansas City, and did all he could to keep the memory alive of that forgotten era. He pushed hard for more negro leaguers to be considered for the Hall of Fame. In 2010, the San Francisco Giants retired his #20.

Before his death, Irvin was the oldest living black man to have played in the major leagues and he was the also the oldest living member of a World Series winning team, having been a part of the 1954 New York Giants.