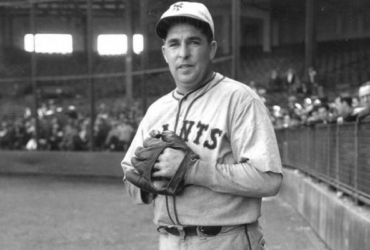

Long before Bartolo Colon was turning heads with his wide ass, soft belly, and large frame, there were other “big-boned” pitchers in baseball. One of the best was Freddie Fitzsimmons, who, like “Big Sexy,” won more than 200 games in a long, successful career.

Fitzsimmons was a portly pitcher with excellent control despite relying heavily on a knuckleball. He combined with Carl Hubbell to form a fine righty/lefty duo on the New York Giants in the 1930s. His trade to the rival Dodgers in 1937 was a shock to his fans who called him “Fat Freddie.”

Fitzsimmons pitched in three World Series and won 217 games with a winning percentage near .600 for his career. After his pitching days ended, he managed and coached in three different decades. Yet, few baseball fans know his name today. At one time he was one of the most popular and well-known players in the game. Now, he’s little more than an entry in the baseball encyclopedia.

Let’s learn about Freddie.

Biography of Freddie Fitzsimmons

Frederick Landis Fitzsimmons was born in Mishawaka, Indiana, a small town just outside of South Bend, located a few short miles south of the border of Michigan, on July 28, 1901. His father gave Freddie the middle name in honor of Henry Landis, a newspaper editor in Indiana. It has been reported that Henry was Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s brother, but that is not true. Freddie’s father later became the Chief of Police in Mishawaka.

Young Freddie was a good student, though he speculated later that his teacher’s may have granted him passing grades because they “were trying to get rid of me.” He excelled in baseball at an early age, when he was larger than most of his peers. His idol was Honus Wagner of the Pittsburgh Pirates, and he also admired Grover Cleveland Alexander. Freddie’s father, who felt “ballplayers and gunmen were close cousins,” had little patience for Fitz’s ball-playing. He wanted his son to be a mill worker of a tradesman. Luckily for Freddie, he spent most of his summers at his uncle’s home in the country, where he had ample time to play catch with his cousins and other children. When he was 15, Freddie learned to throw a knuckleball, and in his own words, “was fascinated to learn every way possible to make a baseball curve.”

Armed with his knuckler and other breaking pitches, teenage Freddie pitched for sandlot teams, gaining notice. A scout passed the word to Doc White, a former major league pitcher serving as manager of a minor league club in Muskegon, Michigan. After a successful tryout, Fitzsimmons was given a contract and made his professional debut at the age of 19. In his first game he hit a double but was called out when he failed to touch first base. Despite the gaffe, young Freddie pitched well, defeating Grand Rapids, and halting their 13-game winning streak. The growing right-hander spent the next two seasons at Muskegon, winning 30 games before earning a contract with Indianapolis of the American Association. In his firsy year at Indianapolis, in 1922, he won six games. The next year he won nine, and improved the figure his last two years with the Indians, winning 14 in 1924 and 14 in just over half a season in 1925. His sharpest game came against Milwaukee, when he allowed a double on the first pitch of the game and thenr etired the next 27 batters for a one-hit shutout.

His performance at Indianapolis did not go unnoticed. On August 8, 1925, Fitzsimmons was signed personally by New York Giants manager John McGraw, and paid dividends immediately, going 6-3 in eight starts. The first major league game he ever saw was the first game he was in uniform for the Giants. The 24-year old made his first major league start on August 16, 1925, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Braves at the Polo Grounds. He defeated Larry Benton, 6-2. In his finest performance of his rookie season, Fitz twirled a 3-0 shutout in the second game of a September 26 twinbill at Forbes Field against the first place Pittsburgh Pirates.

In 1926, Fitz began a nine-year stretch of at least 200 innings pitched, winning 14 games in his sophomnore season for McGraw’s Giants. The next year he copped 17 victories, and followed with 20 in 1928. Over his career, Fitzsimmons won 15 or more in eight separate seasons, but 1928 was his only 20-win campaign.

Want the definition of a freak injury? During spring training with the Giants in 1927, Fitzsimmons was sitting in a rocking chair on the porch of the team hotel when he rocked over the fingers on his pitching hand. His fingers were flattened and he was out of action for three weeks.

Fitzsimmons used a variety of arm angles and deliveries to fool opposing batters. Like Luis Tiant years later, Fitzsimmons would turn his back to home plate, hiding the ball in an effort to thwart the batters’ timing. Leo Durocher, in his biography, Nice Guys Finish Last, wrote: “If you ever saw Freddie pitch, you could never forget him. He would turn his back completely to the batter as he was winding up, wheel back around and let out the most godawful grunt as he was letting the ball go ‘Rrrrrhhhhhooooo!’ like a rhinoceros in heat.”

In spite of the unorthodox delivery and his reliance on the knuckleball, Fitz had excellent control, walking less than two-and-a-half batters per nine innings in his career. The right-hander was also one of the finest fielding pitchers of his era, using his big frame to block balls hit up the middle, and displaying quickness that defied his gravitational weight. He used his body like a hockey goalie, bouncing balls off his chest, arms and legs. Late in his career, the years of pitching had left his body worn: “…his arm was so crooked,” Durocher wrote, “that he literally could not reach down and pick anything up, he had to bend from the knees. It was so crooked that it threw his balance off and gave him a kind of rolling, swaggering gait.”

Generously listed as 185 pounds, Fitzsimmons was more likely close to 205 pounds during his playing career, which earned him the nickname “Fat Freddie.” Likable off the field, and described as a “perfect teammates,” Fitzsimmons was extremely popular with Giants fans. With New York, Freddie learned to ignore the rantings of McGraw, who was notorious for riding his pitchers hard. Lefty Carl Hubbell joined Fitzsimmons in the rotation for nine seasons, from 1928-1936. During that span, Fitz won 121 games and Hubbell garnered 170, as the Giants earned two National League flags.

In 1933, with Bill Terry having replaced McGraw at the helm, the Giants won the pennant and faced Washington in the World Series. Fitzsimmons won 16 games during the regular season, but lost Game Three when his teammates were shutout, 4-0. But it was the team’s only loss, as the Giants won the title in five games. Three years later, in 1936, the Giants were back in the Fall Classic to face the Yankees. “Fat Freddie” started Game Three and lost despite twirling a four-hitter, 2-1. His teammates pounded 11 hits (Freddie had two himself), but were unable to score more than the one tally against the Yankees. On two days rest, Fitz started Game Six, and pitched into the fourth inning before leaving after surrendering five earned runs. The Giants lost that game, 13-5, and the World Series was over.

The Giants were very successful in Fitzsimmons’ years with the team, but that didn’t stop them from slighting him with run support. In 1934, in five starts from September 9th to the 25th, Fitzsimmons lost by scores of 1-0, 2-0, 2-0 and 4-0, winning just once by the tally of 8-1. Fitz earned a reputation throughout his career as a hard-luck pitcher.

Having suffered arm injuries in both 1935 and 1936, and having advanced to the age of 34, Fitz needed to start fast in 1937 to squelch whispers that he was nearing the end of the line. After four starts, which included three unimpressive showings, Freddie was traded to the Dodgers on June 11, 1937, for Tom Baker, a young pitcher. Giants fans were aghast that their favorite right-hander was headed across town to the bumbling Dodgers, who were on the way to their 11th losing season in 16 years. But, Fitzsimmons continued his winning ways, posting a 47-32 mark for the Dodgers in just over six seasons, and within four years he was back in the World Series.

With the Dodgers, Fitzsimmons was a once-a-week pitcher, but he still proved valuable. “Freddie knew how to pitch,” Durocher said, “and he was such a ferocious competitor that I had figured on keeping him around as a spot pitcher and coach until somebaody better came along. Somebody better, huh? In 1940, at the age of thirty-nine, all Freddie did was set an all-time record for National League pitchers. Sixteen wins against only two losses.

Freddie’s first manager in Brooklyn was a perfect match: Burleigh Grimes, a former pitcher who knew looks could be deceiving. “Fat Freddie” looked like he should have been sitting in the stands with a hot dog and a beer, but inside his chest beat the heart of a lion. Grimes stayed out of his way and let Freddie use his knuckle-curve and other assorted pitches to baffle enemy batters. In 1938, Fitz went 11-8 with a 3.02 ERA. In 1940, under Durocher, the 39-year old posted the 16-2 record Leo mentioned above. That season, in just 18 starts, Freddie went the distance 11 times, hurling four shutouts and posting a 2.81 ERA with just 25 walks.

Fitz was a master of the knuckler, and his control of that pitch was legendary. “Fitzsimmons’ chief stock in trade is his fine knuckleball,” wrote Dan Daniel of The Sporting News in 1939, “He throws a mean curve, too. But the famous old butterfly is his marvel…Fitz seems to be able to do more things with that delivery than anyone else. I believe he was the first to get real control over it, and the first to pitch a knuckleball with speed…Fitz always has been able to make it (the knuckler) slow, faster and a bit faster yet.”

Fitz expected to be used sparingly in 1941, serving primarily as a coach. By that time he had ballooned to well over 230 pounds. But Durocher leaned on Freddie to pitch in mid-season, and the veteran responded with a 6-1 record and a 2.07 ERA in 13 games. Fitzsimmons welcomed the opportunity to keep pitching. “Here I am in fine shape, able to pitch, with a vast experience. Here are a hundred kids in the two majors who cannot hold a candle to me. Why should I retire to the lines and become just another traffic cop?”

The Dodgers won the pennant and faced the Yanks in the World Series. Fitz got the nod in Game Three in Ebbets Field, with the series tied at a game apiece. For seven innings he pitched brilliantly, blanking the Yankees on four hits. But the Dodgers were also handcuffed by Marius Russo and were unable to score. In the seventh, Russo lined a pitch back up the middle, hitting Fitzsimmons in the kneecap. Freddie left the game and never pitched in another World Series contest. The Dodgers lost the Series, four games to one.

After the injury in the ’41 Series, Fitz entered spring training in 1942 as one of Durocher’s coaches. During the season he pitched in one game, allowing five runs in three innings. The next season, at the age of 42, Freddie pitched more frequently, posting a 5.44 ERA in nine games, before a new job beckoned. On July 28, 1943, Fitzsimmons was hired by the Philadelphia Phillies to replace manager Bucky Harris. The Phils, mired in seventh place, responded to win their first game under Fitzsimmons, and later racked up a seven-game winning streak. Players responded well to Fitz’s guidance, and he was brought back in 1944. But a last-place finish in ’44, and a miserable 18-51 record the following season, cost Freddie his job on June 29, 1945, just weeks before the conclusion of World War II. The Phillies, a poor team to begin with, had lost all of their better players to the war and were fielding a club with little talent. Fitz never had a chance to prove his worth as a big league manager.

In 1948, Billy Southworth of the Boston Braves gave Fitz a job as his pitching coach. Freddie proved to be a good luck charm, as the Braves won their first pennant in 34 years. The next season, Fitzsimmons was back with Durocher, this time with the Giants, who welcomed back “Fat Freddie.” Fitz served as a coach for the Giants through 1955, as he and Durocher led the team to two NL flags, and a World Series title in 1954. By his third season in New York as pitching coach, Fitz had passed along his philosophy of throwing strikes. The 1952 Giants led the league in fewest walks allowed.

After Durocher was fired in New York, Fitzsimmons coached under Bob Scheffing for the Cubs (1957-1959); with the A’s in 1960; and back with the Cubs in 1966 under Durocher again. By that time, Fitz had been in professional baseball for more than 45 years, and he retired following the 1966 campaign.

Having long since moved to sunny southern California, Fitzsimmons retired to his home in Yucca Valley, where he passed away a week before Thanksgiving, in 1979.

Post-Season Notes

“Fat Freddy” started Game Three of the 1933 World Series, allowing three runs in the first two innings and losing 4-0. He was scheduled to start Game Six, but the Giants won the series in the 10th inning of Game Five. In the 1936 WS, he started Game Three and lost despite twirling a four-hitter, 2-1. The Giants pounded 11 hits but were unable to score more than the one tally against the Yankees. On two days rest, Fitz started Game Six, and pitched into the fourth inning before leaving after surrendering five earned runs. In 1941, with the Dodgers, Fitzsimmons started Game Three in Ebbets Field, but suffered poor run support again, losing 2-1 after seven innings of four-hit ball. He left the game after he was hit on the knee by a line drive (off the bat of Yanks’ pitcher Marius Russo), from which he never fully recovered. In total, Fitzsimmons started four World Series games, going 0-3 with a 3.85 ERA and one complete game. His teams scored three runs for him in the post-season.

Freddie Fitzsimmons: Run Support

| Year | Starts | Runs | RPS | Team | Diff |

| 1925 | 8 | 46 | 5.75 | 4.79 | +0.96 |

| 1926 | 26 | 137 | 5.27 | 4.21 | +1.06 |

| 1927 | 31 | 179 | 5.77 | 5.15 | +0.62 |

| 1928 | 31 | 147 | 4.74 | 5.32 | -0.58 |

| 1929 | 30 | 213 | 7.10 | 5.61 | +1.49 |

| 1930 | 29 | 233 | 8.03 | 5.81 | +2.22 |

| 1931 | 33 | 185 | 5.61 | 4.86 | +0.75 |

| 1932 | 31 | 90 | 2.90 | 5.41 | -2.51 |

| 1933 | 35 | 148 | 4.23 | 4.03 | +0.20 |

| 1934 | 37 | 174 | 4.70 | 5.05 | -0.35 |

| 1935 | 15 | 58 | 3.87 | 5.05 | -1.18 |

| 1936 | 17 | 75 | 4.41 | 4.87 | -0.46 |

| 1937 | 4 | 26 | 6.50 | 4.77 | +1.73 |

| 1937 | 13 | 44 | 3.38 | 4.03 | -0.65 |

| 1938 | 26 | 118 | 4.54 | 4.68 | -0.14 |

| 1939 | 20 | 70 | 3.50 | 4.66 | -1.16 |

| 1940 | 18 | 100 | 5.55 | 4.33 | +1.22 |

| 1941 | 12 | 55 | 4.58 | 5.14 | -0.56 |

| 1942 | 1 | 6 | 6.00 | 4.78 | +1.22 |

| 1943 | 7 | 27 | 3.86 | 4.72 | -0.86 |

| 424 | 2,131 | 5.03 | 4.83 | +0.20 | |

| RPS = runs scored per start by his team Team = runs scored per start by his team in other pitchers’ starts Diff = difference between his run support and that of his teammates |

|||||