What’s the likelihood that one high school will produce the first black man to manage in Major League Baseball and the first black man to coach in the NBA? Has to be a billion to one, right? But that’s how history was written.

Frank Robinson, who died last week after a battle with cancer, became baseball’s first black manager in 1975, and he’s also one of baseball’s greatest players. His former high school teammate Bill Russell became the first black coach in the NBA in 1966. Both Robinson and Russell attended McClymonds High School in the West Oakland neighborhood of Oakland.

Robinson and Russell were born 18 months apart but they were in the same class. Though he was younger, Robinson was the more polished athlete in their teenage years. Tall with tremendously long legs, Robinson was the star of the baseball team, track team, and basketball team, where he played center ahead of Russell. In fact, while Robinson played on the varsity basketball team all four years, Russell remained on the JV squad for two seasons. Even after he moved to the varsity, Russell only scored more than ten points in one game.

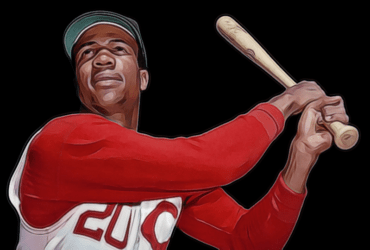

The diamond was where Robinson, or “Robby” as his classmates called him, excelled. Robinson could do everything on a baseball field: hit, hit for power, run, throw, and field. Two things helped him stand out as a young ballplayer. The first was his aggressive baserunning, Robinson was fast and not afraid to flip middle infielders with rolling slides. Second, the tall righthanded batter assumed an intimidating stance at the plate, nearly standing on the plate. This allowed Robinson to reach pitches on the outside of the plate.

The McClymonds High baseball team was one of the best in northern California, a talented squad with two underclassmen with a bright future. The first was Vada Pinson, a lean outfielder who could run like the wind. Pinson was the thorn in the side of coach George Powles. Pinson had many interests that took his eye off the baseball field, one of them was playing the trumpet in the high school jazz band. Pinson had dreams of being the next Miles Davis. His coach just wanted him to learn the hit-and-run sign.

The second young outfielder who played with Robinson in high school was Curt Flood, clearly intelligent even as a young teenager. Flood was quiet and thoughtful, but in the outfield he was assertive and daring. Eventually he would become the best defensive center fielder in baseball, but that wouldn’t be his most famous act. Flood would stare down Major League Baseball’s reserve clause, helping to usher in the era of free agency that ultimately buried players under millions of dollars they never imagined they could make. In doing so, Flood sacrificed his own professional career.

Flood had his distractions too, he loved painting and art. His grandmother dreamed of Curt becoming an art teacher. Flood was the youngest of six kids and his family was poor. He had pressure on him to attend college and the uncertainty of a baseball career weighed on him.

A scout named Bobby Mattick, a former shortstop who played five seasons in the National League, two with the Reds, always kept his eyes on McCleymonds High. He took notice of Robinson when the tall outfielder was only 15 years old. Thanks to his perseverance and a good relationship with Powles, Mattick eventually got his man.

Robinson could have been a collegiate and professional basketball player, he was scouted by teams on the west coast. But he loved baseball and after graduation he signed a contract for $3,500 with Mattick and the Cincinnati Reds. A few years later, both Pinson and Flood, the jazz musician and the painter, would sign similar deals with the same team.

He tore up Class-C ball in Ogden, Utah, was clearly an exceptional player already at the age of 17. The next season he hit .332 with 25 home runs and worked his way to Tulsa. A year later he was in Cincinnati.

In his rookie season, Robinson hit 38 home runs and led the league with 122 runs. He was named Rookie of the Year and more importantly, his arrival helped the Reds improve by 16 wins. If there was one adjective that belonged at the beginning of a list describing Robinson it was “winner.” In 1961 he led the Reds to their first pennant in 21 years. Five years later after Cincinnati traded him because they thought he was too old, Robby won the Triple Crown, his second MVP and led the Orioles to their first championship. In six seasons in Baltimore, Robinson sparked them to four pennants and two World Series titles. From changing team fortunes, Robinson went on to change baseball.

In 1975, Robinson became the first black manager in Major League Baseball when he was hired as player/manager in Cleveland. He later became the first black manager in National League history and won the Manager of the Year Award with Baltimore. Years later, MLB hired him to serve as special assistant to the commissioner. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1982, his first year of eligibility.

Bill Russell, the tall, awkward backup to Robinson at McCleymonds, went on to his own Hall of Fame career as one of the NBA’s biggest stars. Russell became the league’s first black coach in 1966. He guided the Celtics to a pair of titles as a player/coach, giving him eleven total in his career. Obviously, Russell grew out of the awkwardness, becoming arguably the best defensive player to ever lace on a pair of Converse All-Stars.

Robinson and Russell, two tall kids from Oakland, teammates in high school, both grew into Hall of Fame legends. Now we’re left with only Russell.