What do people want from Joey Votto? The answer to that question will tell you what they think of him. But he doesn’t give a damn.

Votto is one of the more singularly unique players in the history of his sport. He does the things most people don’t want to do, or don’t think of doing. He does it better than just about anyone ever has, and like McDonald’s, he does it his way.

His uniqueness may stem from Votto being Canadian. He didn’t grow up with a hockey stick in his hands. “I appreciate how athletically gifted those guys are—I just never got into hockey,” Votto says.

Votto gravitated to baseball, which in Canada is sort of like soccer in the U.S. — there are kids playing it, but it’s still a second-class sport.

Great baseball players don’t come from Ontario for several reasons. First, there are few qualified coaches in Canada who can teach the game. Second, the weather allows for a short baseball season. Votto had to play on a travel team because most Canadian high schools don’t have a baseball program. He was slow and never really took to playing catcher, which was his position in high school. Votto had to take hours of batting practice inside a gym during the cold months, hitting off a tee or scrounging up a friend to throw to him.

“What drew me to the game originally was that it was something I could do solo … an individual game,” Votto told SportsNet for a feature article. “I’m an introvert. To practice [baseball] you could just throw a ball against a wall. A rubber ball. That’s all it takes. Then it was a chance to spend time with my father. I’d play catch with him. He was my first coach when I was seven or eight years old.”

Despite his geographic handicap, Votto developed into a great hitter. The Reds happened on him by accident when he was playing in a tournament in the United States. Over several months they underwent a clandestine operation to scout him, taking great care so they wouldn’t alert other teams to him. Votto thought he might be picked late in the 2002 draft, but instead the Reds snagged him in the second round, afraid that the Canadian teenager might be selected by another big league club.

He spent six seasons germinating in Cincinnati’s minor league system. At Chattanooga as a 22-year old he had his first “Votto-type” season, posting a slash line of 319/408/547. He got a taste of MLB the next season and the year after that he finished second in NL Rookie of the Year voting. From day one in the Cincy clubhouse, Joey was different.

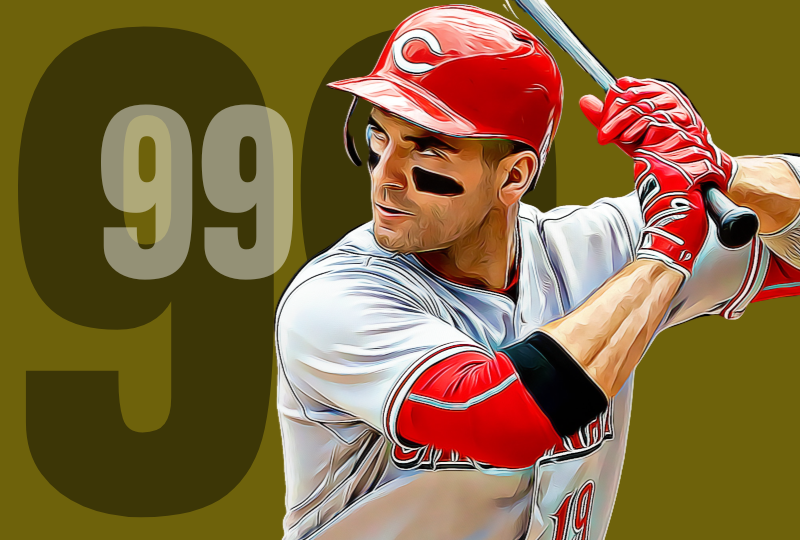

Votto has a crew cut, furrowed brow, dark brushy eyebrows, and wide cheeks. He typically wears stubble that makes him look more like a mysterious villain in a spy movie than an athlete. In his rookie season, asked his secret to immediate success in the big leagues, Votto quipped, “I’m just going to stick with what got me here—shaving every fourth day.”

Votto is an odd duck. (Or maybe a Canadian goose.) He likes to mess around with runners at first base, and he revels in playful banter with fans near his defensive position. He doesn’t have the typical American view of the game. Votto likes to have fun on the field, and with a deadpan, dry sense of humor, he’s one of baseball’s most peculiar players. His favorite trick is to pretend to toss a baseball to a kid in the stands, and then show him the ball still in his possession. He never relents to give the kid a souvenir.

Votto is notorious for his disdain for idle time, which seems to fly in the face of his fondness for watching bad pitches go by. He arrives at the park precisely when he needs to, not a minute earlier. He likes to get out of the clubhouse quickly, scooting through reporter scrums to shower and bolt out the door. He dislikes extra batting practice, preferring to hit off the tee. He also loves to throw a baseball off the wall rather than play catch. He wants to get to the park, get in uniform, get his ABs, and go home. He even once said he would be in favor of seven-inning games.

But shorter games would deprive Cincinnati faithful the treat of seeing Votto manage a plate appearance. He rarely offers at the first pitch, and he’s been known to hop out of the box on a 2-1 pitch, not even feigning interest at swinging. The deeper the count, the more focused he becomes.

“I just do my best to put the ball in play and put it in play where no one’s going to make a play on it and hopefully drive some runners in,” Votto has said.

Pro baseball has seen few hitters like Votto. Maybe half a dozen players in history have been like him. He has an encyclopedic grasp of his batting history, and the ability to recall just how a pitcher has pitched to him. Just like Edgar Martinez. He can see the spin on the ball, and flick his wrists to swat the sphere to any corner of the outfield. Just like Hammerin’ Hank Aaron. And Votto stubbornly refuses to swing at a pitch out of the strike zone. Just like Ted Williams.

How fussy is Votto? He won’t swing at a fat, juicy fastball even if it’s an inch off the plate. He won’t swing his bat at a breaking pitch that hangs helplessly just north of the strike zone. “Mr. Finicky” won’t chase.

The results are startling: seven times Votto has paced the league in getting on base. Three times he’s reached base more than 45 percent of the time. Through the age of 33, he’s had eight 300/400/500 seasons. That’s two more than Frank Robinson, and three more than Alex Rodriguez ever had. His career .421 on-base percentage is the best in Cincinnati Reds’ history. His career OPS is the highest for a Red batter too. Better than Robinson, Pete Rose, and Johnny Bench. Better than the Reds’ Hall of Fame first baseman Tony Perez. His skill at getting on base, for drawing walks, is legendary.

Maybe someone should call Votto, “The Big READ Machine.”

Every front office, and every scouting department keeps track of where every batter hits the ball. It’s called a “spray chart.” Most charts end up in one of a few categories, and as you pour through them they meld together. But Votto’s spray chart is unusual, it pops out. It’s like glancing at children’s refrigerator artwork and then looking at a Rembrandt. During a three-year stretch in his prime, Votto had more extra-base hits to left field than any batter in the league, and he’s a left-handed hitter. He also had the most base hits to center field, and the most extra-base hits to right field. How do you defend against the indefensible? How do you counter a batter who won’t swing at bad pitches and hits the ball to every area of the field? You can’t, and that’s why Votto ranks 27th all-time in OPS and 17th in on-base percentage.

Votto gets on base more often than Frank Thomas did, and more than Stan Musial did. His on-base percentage is better than Mickey Mantle.

But not everyone has been enamored with Votto’s offensive philosophy. Writers, the Cincinnati play-by-play broadcaster, and even a few teammates, have wondered if Joey should swing the lumber more often when runners are on base. The numbers are revealing.

In his age-26 season, Votto slugged 37 home runs in 150 games and was named MVP. He walked 91 times that year, showing the aggressiveness to drive in 113 runs. Over his next five years, he averaged 25 homers per 162 games, and his RBI total shrunk to 83 per. Meanwhile, his walks per 162 games exploded to 131. All too often, according to some, Votto was trotting to first base rather than driving in the runners in front of him.

At the most elemental level, the best thing a batter can do is not make an out. That can be accomplished only a few ways: place the ball in play where no one can put you out, or coax a base on balls. Votto is one of the best ever at doing both. But he won’t violate his dedication to swinging only at good pitches in order to do the first thing. It’s too much of a risk. His hero is Ted Williams, who famously hated to swing at bad pitches. Votto keeps a worn copy of Williams’ “My Turn At Bat” in his locker.

Walks and fewer swings are not exciting. Home runs, launch angle, (and the strikeouts that accompany them) are in vogue. But Joey Votto is not normal. He’s peculiar, even mundane in his excellence.

“I strive for boring in all elements of my game,” Votto has said.

But boring can be beautiful.