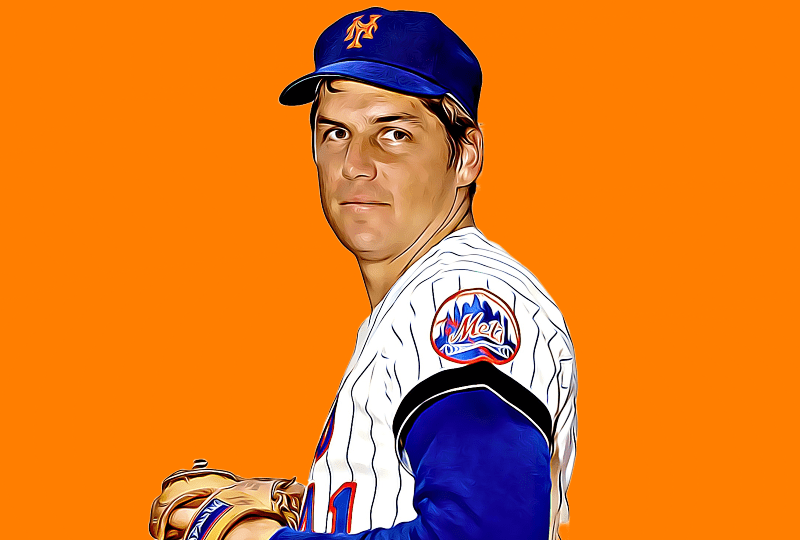

When Tom Seaver arrived off the campus of the University of Southern California and joined the Mets organization, he was a fresh-faced star and a savior-in-the-making. Within a few years, he went from BMOC to BMOM (Big Man on Manhattan).

Quickly, in fact much quicker than anyone imagined, Seaver delivered on his promise, and led the Mets to the most improbable and miraculous championship in any of the four major professional sports. Mets fans never forgot him, even if they tried in order to heal their broken hearts.

Seaver was the prize in a much-publicized three-team “lottery drawing” in 1966 when the Phillies and Indians also vied for his services out of college, but the Mets were drawn out of a hat in the commissioner’s office. He was a physically mature big league pitcher from his first start for the Mets when he was 22 years old. He had a once-in-a-generation arm.

Seaver was built like a tree stump, supported by powerful legs. In his third start he pitched a ten-inning four-hitter against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Nerves? What nerves?

The New York spotlight was perfect for the kid from California: the team was woeful, expectations were low, every fourth day all eyes were on him. He was “Tom Terrific.”

In 1969, Seaver was remarkable, he started 35 games and in 24 of them he allowed zero, one, or two runs. He won 25 games, threw five shutouts, and got better as the season drew to a close. Seaver went 7-0 after August 31st with seven complete games, three shutouts, a 0.71 ERA, and he did not allow a home run in September. He pitched ten innings in his Game Four victory in the World Series, helping the “miracle” become reality for the Mets. Broadway Joe, Broadway Schmoe…Seaver was the superhero in the Big Apple.

In the four years after The Miracle, Seaver led the league in ERA and strikeouts three times. He could have won the Cy Young every year, probably should have. He was the greatest pitcher since, well who knows…maybe Lefty Grove. Hell, maybe “Big Train” Walter Johnson. Every one of his starts was must-see, and Shea Stadium was his stage. He had a breaking ball that made knees buckle, command of everything that left his right shoulder, and that sizzling fastball.

“Blind men come to the park just to hear him pitch,” Reggie Jackson said.

Seaver will always be the greatest Met because he was the first great Met. He seemed like the first real Met. He felt like royalty, he felt like he came down from outer space and decided to show lowly humans how to pitch. He was the rarest of young gunslingers: he was never a thrower. He could pitch immediately.

To Mets fans, Seaver is the icon, the god, all four faces on the franchise’s Mt. Rushmore. Who can possibly share that space with the greatest arm since the first Deadball Era? Dwight Gooden, Mike Piazza, David Wright? Too little, too late, and too fragile. Seaver was formidable. He was a serious man in a serious city, with a golden arm.

There are few happy endings in baseball. Few in life, really. And given the dysfunction in the Mets front office, it was inevitable that Tom Terrific would have to pack his bags.

Seaver’s exit from New York was dramatic, acrimonious, and controversial. It was the “Lebron James Leaves Cleveland” story of its day. Baseball was changing in the mid-1970s. Free agency was blooming, and every winter the headlines reported on the latest ballplayer millionaires. The players’ union was essentially undefeated, and Tom Seaver was possibly the most astute member of the union. He knew his worth, he knew the financial possibilities afforded to him, and he typified the new generation of athletes who demanded respect. He refused to kowtow to management.

Tom was due to enter the free agent market following the 1977 season but wanted a three-year deal to stay with the Mets. The chairman of the board for the Mets was M. Donald Grant, a humorless man who had been in the front office since the team’s inception. Grant had no intention of making Seaver baseball’s highest-paid pitcher.

The feud played out on the back pages of the New York tabloids as the ‘77 campaign wore on. It culminated with a scathing article by Dick Young (a Grant sycophant) that lambasted Seaver for his greed. Young invoked Seaver’s wife in the article, blaming her for some of Seaver’s “selfishness.” Predictably, that pissed off Seaver, who circumvented Grant and went directly to team owners, demanding a trade. In June, he was dealt to the Cincinnati Reds just before the trade deadline expired, as part of what became known as “The Midnight Massacre.” Grant also traded slugger Dave Kingman at the exact same moment.

Seaver went 14-3 for the Big Red Machine in 1977, and he gratefully signed a four-year, $1.5 million deal to remain in Cincinnati. The Mets finished in last place for three consecutive seasons and Grant was fired in 1978.

The city of New York, the Mets fans there, never recovered from Seaver leaving the team. It was said that New York went into a “mourning phase” after Seaver’s exit. He came back, a 38-year old ace emeritus, no longer a strikeout king, for one final season with the Mets. In his first start at Shea Stadium on Opening Day in 1983, the first batter he faced was former teammate Pete Rose. Seaver pumped a few fastballs by Charlie Hustle and struck him out. The Shea Stadium crowd did something unusual: they gave Tom Terrific a standing ovation during the entire at-bat.