For all the nicknames bestowed on Babe Ruth, and there were many, his teammates most often called him “Jidge,” which is German slang for George. In contrast, Ruth called almost everyone “Kid,” because he didn’t bother to remember names.

Ruth’s parents were German, and on occasion, when he wanted to really let Lou Gehrig know that he appreciated something he did on the field, the Babe would congratulate his teammate in that language, which they sometimes spoke in the clubhouse.

Teams used to play their way north after spring training, scheduling exhibition games along the way. In the spring of 1921 the Yankees stopped in Baton Rouge, Louisiana to play a game against a local team. After the game everyone piled onto a train: the team officials, sports writers, players. On this afternoon, with a dozen writers sitting in the media car, the doors sprung open and Babe Ruth came running down the aisle with an angry woman chasing him, a butcher knife in her hand. Ruth darted out the other side of the car, hopped on the railroad platform, ran the length of the train, and climbed back on a railcar just as the engine pulled away, escaping the blade of the woman. There are dozens of stories like that about Ruth. Once in Detroit, a man with a gun chased the Babe through a hotel lobby while his teammates watched in horror. A few moments later, Ruth reappeared and bought a round of drinks for his pals. Yet none of those stories saw a printed page while Ruth was alive, that was the way journalism worked in those days. Secrets were kept.

An economist named Michael Haupert estimated that 37 percent of the profit the Yankees earned while Ruth was on the team could be attributed to the Big Fella. Until Larry Bird and Magic Johnson came along, no athlete was more important to their team and league.

RELATED:

100 Greatest Players of All-Time

Greatest Right Fielders in Baseball History

New York Yankees All-Time Team

Babe Ruth’s Superstitions

Ruth had a number of superstitions. When he came to the batting cage for his practice swings before a game, Ruth always tapped the plate with his bat, and he liked to hit a home run over every wall, in left, center, and right, before ending batting practice. He believed a bat only had so many hits in it, and he refused to loan his bats to teammates. When the Babe went out to his position in right field he always stepped on second base, and at the Polo Grounds and later Yankee Stadium, he would tip his cap to familiar fans who sat in seats in right field or behind the plate. If he didn’t see a regular fan in the stands, Babe would send a batboy to find out why they were missing. Like many ballplayers, Ruth despised trash on the field, and he would obsessively retrieve stray scraps. He also believed in lucky charms: for several years before games in New York, the Babe would rub the head of a mascot, a short black man who worked in the clubhouse.

Ruth was famous for using a heavy bat, the largest he used weighed 54 ounces. But as he grew older, Babe switched to lighter bats until he was using a thin-handled 36-ouncer in his final years. He was one of the first (if not the first) batter to curl his fingers around the knob of the bat. He said he liked to do that to help him finish his follow-through. Like many stars, Ruth took special care of his bats. Each spring, Babe visited the Hillerich & Bradsby factory in Louisville to hand pick the wood used for his bats. He signed with H&B to use the Louisville Slugger brand in 1918 for $100 and a new set of golf clubs.

Miller Huggins used to switch the Babe from right to left field depending on where the sun was. He didn’t like Ruth playing the sun field. The statistical record doesn’t show it, but Ruth had dozens of games where he played right for a few innings, switched with Bob Meusel, and played the rest of the game in left. Huggins didn’t want anything taking Babe’s mind off swinging a bat, even sunlight.

In spring training and exhibition games, and at the end of the regular season after the Yankees had clinched the pennant, Ruth would play first base and Lou Gehrig would move to right field. The Babe liked to play first so he could be closer to the fans, and he also didn’t like to make the long walk to the outfield. As a result, there are thousands of people who got Babe’s signature on a baseball because he would walk over to the stands in the middle of a meaningless game and scribble.

Babe Ruth: “Greatest Crowd Pleaser”

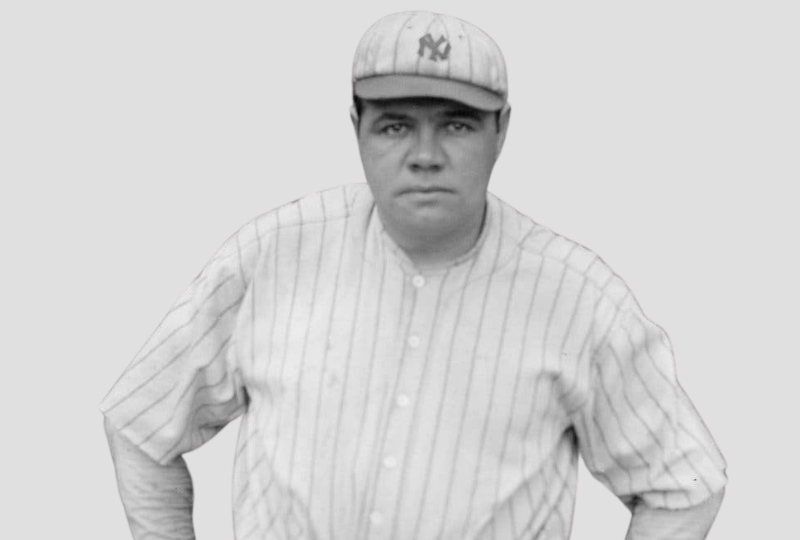

Ruth left his mark on the game like no other. He was an overgrown kid, an ungovernable force who swept his way through the sporting world, dominating headlines every year after he became a Yankee until his death nearly three decades later. He was the walking epitome of the Roaring Twenties, America’s first sports superstar: The Behemoth of Bust, The Caliph of Clout, The Colossus of Clout, The Great Bambino, The Wazir of Wham, The King of Crash, and The Sultan of Swat. They kept coming up with nicknames for him because nothing seemed to capture his greatness. He was the original, the only, the once-in-a-lifetime.

Ruth broke every home run record, and every slugging mark of any sort. But his fame and greatness wasn’t born in numbers. It was born from the feeling he gave those fortunates who saw him launch baseballs high into the sky and far over fences. He was a performer as much as he was a champion. His teammate, pitcher Waite Hoyt, said of the Babe:

Will there ever be another Ruth? Don’t be silly! Oh sure, somebody may come along some day who will hit more than 60 homers in a season or more than 714 in a career, but that won’t make him another Ruth. The Bambino’s appeal was to the emotions. … I’ve seen them: kids, men, women, worshipers all, hoping to get his famous name on a torn, dirty piece of paper, or hoping to get a grunt of recognition they said “Hiya, Babe.” He never let them down, not once! He was the greatest crowd pleaser of them all! It wasn’t so much that he hit home runs, it was how he hit them and the circumstances under which he hit them. Another Ruth? Never!

Waite Hoyt

The Babe was not only larger than life, he seemed to be larger than death. At his funeral on a searing August day in 1948, former teammates Joe Dugan and Hoyt suffered in the humidity, clawing at their neckties. “I sure could go for a cold beer,” Hoyt said. “So could the Babe,” Dugan replied.