In February of 1935, Babe Ruth turned 40 years old. He had spent the last 15 years with the New York Yankees, after coming over from the Boston Red Sox. His slugging feats and larger-then-life persona had changed the face of baseball.

With the Sox in 1919, Ruth hit 29 homers, breaking the single-season home run record of 27, set in 1884 by Ned Williamson. Then with the Yankees in 1920, he broke his own record with 54. In 1921, he broke it again with 59. After breaking the single-season home run record three years in a row, he waited until 1927 to do it again, with his famed season of 60 round-trippers.

In 1921, he also set a new career home run mark, surpassing the 138 round-trippers of Roger Connor, who had retired in 1897. When the 1934 season ended, Ruth’s career total stood at 708 home runs. That put him 360 career homers ahead of his nearest rival, long-time teammate Lou Gehrig, in second place with 348. At that point, Ruth had more than twice as many home runs as anyone in the history of the major leagues.

But 1934 had not been a good year for the Babe. His knees were painful, his midsection had continued to grow, his body was breaking down, and his on-field production had declined considerably. Simply put, The Babe was an old 40. He seemed ready to retire as a player, but for years he had coveted the job as Yankees manager. As author Jane Leavy wrote in her biography of The Babe, Ruth “fumed, pouted and turned surly when Chicago Cubs manager Joe McCarthy was hired…in 1931.” But McCarthy had led the Yanks to the World Series title in 1932 (and would soon lead them to four more titles in a row). Yankees owner Jake Ruppert had no intention of letting McCarthy go.

Instead, it was time for the Yankees to let Babe Ruth go. Of course, the Yankees had to find a way to do that gracefully; it would not look good to simply “dump” The Babe. If a manager’s job with another team were available, and offered to Ruth, he might accept it. However, none of those jobs were available. Would another team offer Ruth a contract strictly to be a player? And would Babe accept that? Certainly not if it was merely for a pinch-hitting role, or to be a backup. So how could the situation be resolved?

On February 23, 1935, Boston Braves owner Judge Emil Fuchs wrote a carefully worded letter to Ruth which might offer a solution. Judge Fuchs stroked Ruth’s ego, praising him as a “great asset to all baseball.” He invited The Babe to join the Braves “to play in the games whenever possible,” and also to “participate as assistant manager.” In addition, he offered Ruth an “official executive position” (later specified as vice president) with the club. Perhaps most enticing to Ruth was a reference to the possibility that after the 1935 season he might be able to “take up the active management on the field.” The letter alluded to other possibilities. Author Robert Creamer called the letter “in its way, a masterpiece.”

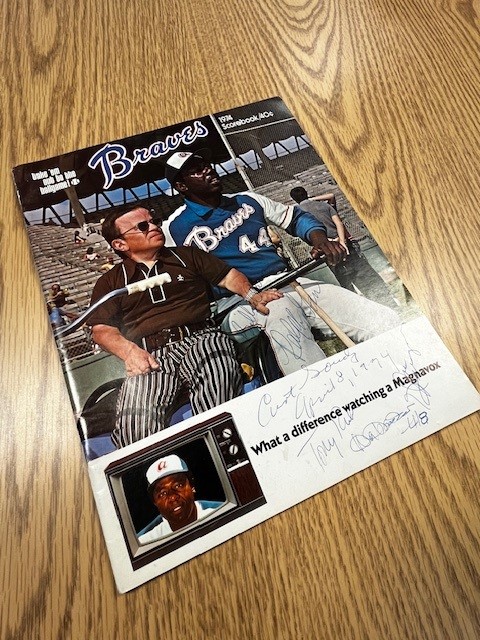

1974 Atlanta Braves program, signed by Braves outfielder Ralph Garr and NBC broadcasters Joe Garagiola, Curt Gowdy, and Tony Kubek. (Photo by Bill Francis)

After confirming with Ruppert that becoming manager of the Yankees was not in the cards, Ruth met with Ruppert and Fuchs to discuss the details regarding his departure from the Yankees and move to the Braves. A contract with the Braves reflected the letter from Fuchs, but the language seemed to blur the line, at least for Ruth, between what was guaranteed and what was not. Creamer wrote that Ford Frick, President of the National League, “noted that much of what Babe thought he had been promised was not in the contract.”

The next day, the two owners and Ruth held a press conference. Ruppert said that the Yankees would not stand in Babe’s way given the opportunity he had been offered with the Braves. Ruppert emphasized that the Yankees were gaining no compensation, and giving Ruth his unconditional release. The questions of what Babe would do as vice president and exactly what the role of “assistant manager” meant were largely glossed over. In the end those titles essentially amounted to virtually nothing, as did expectations Ruth had toward becoming manager of the Braves.

But Babe Ruth was taking the field again. When he first returned to Boston, this time as a Brave, he homered. Unfortunately, it was soon apparent that his skills had seriously eroded. When the Braves took the field on the afternoon of Saturday, May 25, Ruth was batting .153 with three home runs for the season. His end as a player was near. The team was in Pittsburgh to play the Pirates at Forbes Field.

Before the game Pittsburgh’s starting pitcher, Red Lucas, was trying to decide what pitches to throw The Babe. His Pirate teammate, Guy Bush, suggested sinkers. So in the first inning Ruth came to the plate and Lucas threw a sinker. Ruth knocked it over the right field fence for a home run. Soon Bush was throwing in relief of Lucas. When Bush faced Ruth, he took his own advice and threw a sinker. Ruth knocked it over the right field fence for a home run. The next time Babe came up, Bush again stuck with the sinker; this time he held Ruth to a single.

In an interview with the South Bend Tribune that Bush gave just prior to the 1974 season, the retired pitcher remembered how the events to that point “made me so mad.” So when Bush faced Ruth one more time in the seventh inning, he decided to forego the sinkers and go with fastballs. He was thinking, “I’m going to throw three fastballs right by that guy and see what this crowd will do and get my laugh on him.”

So Bush threw a fastball and Babe just watched it go by. Bush threw Ruth another fastball “with everything I had on it. He got ahold of that ball and hit it over the triple-deck, clear out of the ballpark in right-center. I’m telling you, it was the longest cockeyed ball I ever saw in my life.”

As Ruth rounded third base, he looked at Bush. “I tipped my cap just to say, ‘I’ve seen everything now, Babe’…and that’s the last home run he ever hit.”

It was the first home run ever hit completely out of Forbes Field, clearing the 86-foot high grandstand in right-center field. Ruth left the game having gone 4-for-4, with a single, three homers and six RBIs.

The next day, Sunday, May 26, the New York Times featured an article on the first page of the sports section. The article, with a byline of May 25, began…

Rising to the glorious heights of his heyday, Babe Ruth, the sultan of swat, crashed out three home runs against the Pittsburgh Pirates today, but they were not enough and the Boston Braves took a 11-to-7 defeat before a crowd of 10,000 at Forbes Field.

With respect to Ruth’s third homer, the article described it as follows:

A prodigious clout that carried over the right-field grandstand, bounded into the street and rolled into Schenley Park. Baseball men said it was the longest drive ever made at Forbes Field.

Those close to Ruth urged him to retire after the game, thinking it best for him to “go out on top,” but Babe played a few days longer to keep a promise he had made to Judge Fuchs. He then finally stepped away from the game. His monumental home run was the last hit, and the 714th regular-season home run, of his career.

While the final three home runs of Ruth’s career had occurred without any anticipation, with relatively little media fanfare, and with a small crowd in attendance, the pursuit of his record by another player would stand in stark contrast. During the latter stages of the 1973 season and the early days of 1974, baseball fans and media became obsessed with Hank Aaron’s chase of Ruth’s career home run record. After all, the record had stood for nearly 40 years, creating a sense of expectation for a new record that some observers had once considered unattainable. The home run chase also brought with it controversy and strife, principally in the form of racism that Aaron endured while trying to stake claim to the game’s most glamorous individual record.

Aaron had experienced racial bigotry throughout his life, including Jim Crow segregation that affected him while playing in the 1950s and sixties. In 1952, he had signed with a Negro Leagues team, the Indianapolis Clowns, who played in the Negro American League. Even though Jackie Robinson had integrated the established major leagues five years earlier in 1947, the Negro Leagues continued to exist into the 1950s (and in a lesser form, into the 1960s).

Even after leaving the Clowns and signing with the Milwaukee Braves’ organization, Aaron continued to suffer the stings of segregation, particularly during his 1953 season with the Jacksonville Tars of the South Atlantic League (also known as the Sally League). It was Aaron himself, along with teammates Felix Mantilla and Horace Garner, who integrated the Sally League that summer. That pioneering effort came at a difficult price, as Aaron received death threats and was targeted with racially-charged insults at various ballparks.

Over the course of his long career in Milwaukee, Aaron would gain more racial acceptance, aided in part by his emergence as one of the game’s true superstars. But like other Black players on the Braves, Aaron became concerned when the franchise relocated to the South in 1966, making Atlanta its new home. Even with the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, many southern cities remained married to their Jim Crow past, with segregation still in place in housing, restaurants, and other locations. But most Atlanta fans came to accept the great Aaron.

Then came the home run chase, which first started to garner attention during the 1972 season, as Aaron’s home run total approached 670. By the end of that season, he was just 44 behind Ruth.

The chase began to achieve a fever pitch during the summer of ‘73. Writers peppered Aaron with questions about breaking The Babe’s record. In his typical manner, Aaron remained patient, never losing his temper with the writers.

That summer also marked the beginning of a disturbing trend; Aaron was receiving a growing number of letters from so-called fans expressing their resentment of his skin color. While some of the letters battered him with vile epithets and insults, others struck an even more vicious tone, either implying or directly stating threats against Aaron’s life. One of the worst of those letters gave Aaron an ultimatum. “Retire or die! The Atlanta Braves will be moving around the country and I’ll move with them,” said the writer of the letter. “You will die in one of those games. I’ll shoot you in one of them…You will die unless you retire!”

The Braves contacted the FBI for its assistance. The bureau began to read the mail, and in some cases, dig deeper into their origins. The Braves hired two off-duty Atlanta police offers to serve as Aaron’s personal bodyguards. They arranged for policemen Lamar Harris and Calvin Wardlaw to attend each Braves game and observe potential threats from the stands. For his part, Wardlaw equipped himself with a .38-caliber Smith and Wesson.

At the end of 1973, the United States Post Office awarded Aaron with a plaque, acknowledging that he had received over 930,000 pieces of mail, the most for any non-politician in America. While some of the letters were hateful, most were not. According to Aaron, the “overwhelming majority” of the letters offered positive support in his chase of Ruth’s record. According to Aaron, those letters provided him with an emotional boost that he found helpful at one of the most difficult times of his career.

By the end of the 1973 season, Aaron had hit 713 home runs, leaving him one short of Ruth’s record. That meant that Aaron would have to face a winter of more unwanted anticipation and pressure. Other problems would develop, beginning in February of 1974. Braves president Bill Bartholomay announced that the team planned to bench Aaron for the entire season-opening series in Cincinnati. That would increase the odds that Aaron would hit his tying and record-breaking home runs at home, in front of sellout crowds at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium.

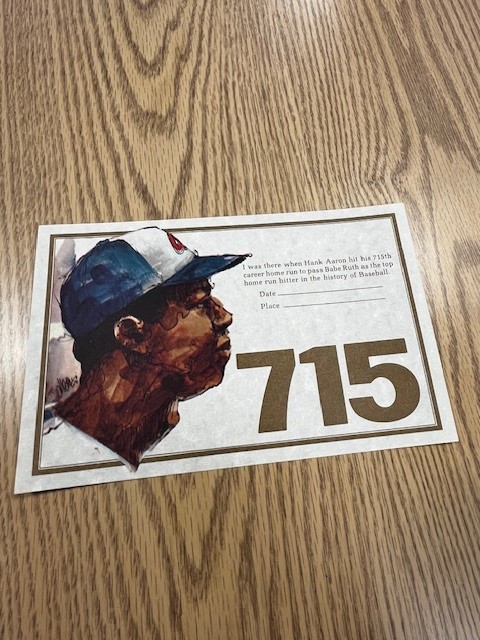

The above photo shows a certificate of witness given to each fan who attended the April 8th game in 1974. Photo credit: Bill Francis of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Bartholomay’s announcement was met with severe criticism from the baseball media. Writers ripped the Braves for damaging the integrity of the game by keeping a healthy star player out of the lineup just to protect their financial interests at home. Even though Aaron had just turned 40, the same age that Ruth was when he hit his 714th, he was still Atlanta’s best player. In 1973, he had delivered another vintage season, batting .301 with 44 home runs.

Among the critics of the Braves’ decision to bench Aaron was veteran writer Dick Young, a columnist with the New York Daily News and The Sporting News. Never one to hold back, Young held the Braves accountable with his vitriolic words, writing that “Baseball has gone crooked.”

After a few weeks, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn chimed in by issuing a formal statement, putting the Braves’ organization on notice. “Barring disability, I will expect the Braves to use Henry Aaron in the opening series in Cincinnati, in accordance with the pattern of his use in 1973, when he started approximately two of every three Braves games.” Even as commissioner, Kuhn did not have the authority to force the Braves to play Aaron. Still, he managed to deliver a subtle but clear message that he wanted Aaron in the lineup for at least two of the games in Cincinnati.

In response to Kuhn, and the backlash from the general public, the Braves reconsidered their position. They announced that Aaron would play in Cincinnati—for at least two of the games. So on Opening Day at Riverfront Stadium, Braves manager Eddie Mathews penciled Aaron’s name onto the lineup card, batting him cleanup and playing him in left field.

On a sunny Thursday afternoon in Cincinnati, the Braves faced veteran right-hander Jack Billingham. With one out and two runners on in the top of the first, Aaron stepped to the plate. He watched the first four pitches thrown to him, not offering at any of them. And then on his first swing of the season, Aaron lofted the pitch toward left field. The ball carried, clearing the left-center field wall. The blast placed Aaron in a first-place tie with Ruth for the all-time home run lead, both at 714. (And in a footnote, Aaron had become the first player to hit a home run using baseball’s new cowhide ball, which had replaced the standard horsehide to start the new season.)

Aaron’s home run gave the Braves an immediate 3-0 lead, but also placed Eddie Mathews in a precarious situation. How much longer would Mathews play Aaron that day, knowing that the next home run would break Ruth’s record and deny Atlanta fans the chance to witness history in person? Mathews gave Aaron three more plate appearances – a groundout, a walk, and a fly out – before removing Aaron for a defensive replacement. The Braves would give up the lead and lose the game in extra innings.

After the traditional off day following the opener, the Reds and Braves resumed their series on Saturday afternoon. Keeping with the plan to give Aaron at least one day off in Cincinnati, Mathews sat down Aaron, replacing him with Ralph Garr. Without Aaron, the Braves lost to the Reds, 7-5.

In response, Commissioner Kuhn felt that the Braves were taking his declaration of Aaron playing “at least two games” in Cincinnati a bit too literally. Kuhn publicly “requested” that Mathews play Aaron in the final game of the Reds’ series. In response, Mathews asked the commissioner if he was giving him a direct order to play Aaron. According to what Mathews told the media, Kuhn told him that it was indeed an “order.”

Aaron played on Sunday, but did not do well. He came to bat three times, striking out twice and hitting a weak ground ball to third base. Mathews did not give Aaron a fourth at-bat, removing him for what he called “defensive reasons.” The Braves held on to win, 5-3.

With Aaron still at 714, the scene was set for the evening of April 8 in Atlanta. Aaron and the Braves played host to the Los Angeles Dodgers in front of a sellout crowd of 53,775 at Fulton County Stadium. NBC carried the game as part of its Monday Night Baseball package, giving fans across the country a chance to witness one of the game’s grandest moments.

Mathews inserted Aaron, his left fielder, into the cleanup spot. Aaron would face veteran left-hander Al Downing, a 20-game winner in 1971 who was now in the latter stages of his career. In the bottom of the first, Downing retired the Braves in order.

Aaron, leading off the second inning, settled for a walk against Downing. Aaron then came home on a double by Dusty Baker, and in so doing, made a bit of history that went largely unnoticed. That run broke Willie Mays’ record for the most runs scored in National League history.

In the fourth inning, Aaron came to bat for a second time. With the Braves trailing 3-1, two men out, and a runner on first, Aaron stepped in against Downing. The first pitch was a change-up that sank low into the dirt. The crowd booed at the unhittable pitch. With his next delivery, Downing threw a fastball. Without much velocity, the pitch stayed up and near the center of the plate.

It was a pitch too good for Aaron to let go. He delivered one of his typical swings, heavy on the top hand and level to the ground, as he lifted the pitch deep toward left-center field. Like most Aaron drives to the outfield, it was not a particularly high fly, but one with a lower trajectory. It carried well toward the gap, pushing left fielder Bill Buckner and center fielder Jim Wynn toward the left-center field wall. Closer to the ball, Buckner climbed the wall, hoping that he could extend his body and make a dramatic catch. But Buckner had no chance to make a play, the ball carrying several feet beyond his reach. The ball landed in the glove of Braves relief pitcher Tom House, who was standing in the Atlanta bullpen. It was a home run.

It was the home run, the 715th of Aaron’s major league career, the one that put him atop the all-time list, one more than The Babe. As the fans erupted, Aaron continued his home run trot. After rounding second base, where he was congratulated by two Dodgers, Davey Lopes and Bill Russell, he was suddenly met by two young men who had jumped the fence at Fulton County Stadium and made their way to the middle of the field without resistance. For a moment, bodyguard Calvin Wardlaw, watching from the box seats, considered reaching for his gun, which he carried in a binoculars case, and taking aim at the two intruders. But Wardlaw never removed the gun from its case. He quickly realized that the men, who were patting Aaron on the back, intended no harm. It became obvious to Wardlow that they were simply two fans who had decided to make themselves part of the celebration. (For that, they would spend the night in jail, but both would eventually become friendly acquaintances of Aaron.)

By the time Aaron reached home plate, his legion of well-wishers numbered nearly a dozen, but these folks were authorized; they included some of his teammates and coaches, and a member of the media. They were soon joined by more players and a bustling group of writers and reporters, along with members of Aaron’s family, including his parents. Aaron’s mother quickly took hold of her son, refusing to let go.

As the gathering at home plate grew larger, Vin Scully, during his play-by-play on the Dodgers’ broadcast, did his best to offer the proper perspective. “A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol,” Scully announced over the air. “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world.” And as Scully said many years later, that home run was “the most important home run that I ever called.”

For Aaron, it was a home run that brought a sense of relief, ending the unrelenting pressure of beating The Babe’s record and bringing to an end the onslaught of hate mail and death threats. For many fans lucky enough to watch that historic event in person, or observe it on national television, it was a monumental moment – and the most memorable home run they would ever witness.

Ron Visco worked as a museum teacher at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for 25 years.

Bruce Markusen is an educator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum and an author of several books on baseball history.