The Baseball Writers Association of America recently announced that they will rename their most prestigious award.

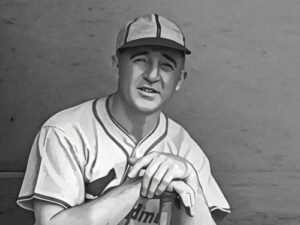

The J.G. Taylor Spink Award, given annually to a baseball writer for his meritorious service to the game, is being renamed. Each year, the winner of the award is honored during Hall of Fame Weekend ceremonies in Cooperstown.

The BBWAA will remove Spink’s name and rename the honor the BBWAA Career Excellence Award.

During his tenure as publisher of The Sporting News (from 1914 until his death in 1962), Spink illustrated a disagreeable (some might say indifferent) attitude toward integration of Major League Baseball, which excluded black players until Jackie Robinson debuted in 1947.

In an editorial he penned in 1942 titled “No Good From Raising Race Issue,” Spink argued that a black player would face humiliating criticism in the white major leagues. The publisher believed that both the white majors and the black negro leagues should remain segregated for the sake of the black and white players, who, according to Spink, “both sides would prefer to be let alone.”

Spink also repeated an opinion of many at the time: that if black players migrated to the major leagues, the negro leagues would be destroyed, thus causing economic heartache. But mostly, according to his editorial, which was published in the August 6, 1942 issue of The Sporting News, Spink was concerned with the mixture of black and white players prompting violence.

“It is not difficult to imagine,” Spink wrote, “what would happen if a player on a mixed team performing before a crowd of the opposite color, should throw a bean ball, strike out with the bases full or spike a rival.”

Later in the decade, after Robinson had broken the color barrier, Spink’s paper, which was acclaimed as “The Bible of Baseball,” published articles that questioned integration. The Sporting News would even list low batting averages of black players and question whether integration came too soon.

Spink’s problematic stance on race brings to question whether the publisher was racist. Spink’s paper had great power over the promotion of organized baseball, and his opposition to integration may have stalled efforts to shepherd black players into the big leagues. The Philadelphia Phillies had hinted at stocking their roster with black players during World War II, but given Spink’s warnings of racial mixing on the diamond, and the power Landis held over the game, that idea was dead in the water.

In the current era, with the term “cancel culture” often tossed around, the Spink legacy is troublesome. On the one hand, Spink’s ideas were held by many (if not the majority) in America at the time. In fact, in his editorial mentioned above, Spink quotes two prominent black leaders of negro league baseball, both of whom are opposed to integrating the white major leagues. Their reasoning mirrored that of Spink: fears of violence in the stands and the devastation of black-owned teams in the negro leagues.

But the erasure of Spink’s name from the writers award (an award he himself won just before his death) is not a case of cancel culture. The Baseball Writers Association of America polled their membership and found overwhelming support for the action.

“This action was not taken lightly,” said BBWAA president C. Trent Rosecrans. “It was put to a vote after substantial research and conversation with and among members.”

Given Spink’s clear opposition to integration and the way The Sporting News continued to treat black players on their pages in the years after integration, it’s a wise move to remove his name from the award. Last year, Major League Baseball announced that they were removing Landis’ name from the Most Valuable Player Award. During his control of the game, which stretched from 1920 until his death in 1944, Landis was open about his distaste for black players entering the league.

In a 2013 article, baseball writer Craig Calcaterra revealed that Spink and Cleveland owner Bill Veeck feuded over black pitcher Satchel Paige’s status as a major leaguer. According to research by Calcaterra, Spink called Veeck’s signing of Paige, widely recognized as the greatest pitcher in negro leagues history, a “publicity stunt.” When Veeck later confronted Spink after Paige had proved valuable on the mound, Spink deflected the argument and claimed the quality of play in the big leagues was weaker than it had ever been. Such an opinion makes it difficult not to view Spink as having prejudicial views on black athletes.

Still, it’s not a simple matter to judge the intentions of people who are no longer here to defend themselves. Yes, Spink was opposed to integration, but he explained in his editorial that it was for other reasons than race itself. Then again, it’s not hard to imagine that Spink’s public opinion masked a deeper prejudice against African Americans. The Sporting News was slow to champion players of color, even after Robinson became a star. Often, Spink’s paper seemed amazed that black players were having such success.

It seems appropriate to point out that Spink did good during his career as well. President Harry S Truman issued a commendation to Spink for the service The Sporting News played during World War II. “News from home was of vital interest to members of the United States Armed Forces,” Truman wrote in a letter that accompanied the commendation. “The military editions, which you developed and maintained on a high standard, made an effective contribution to the morale of our troops.”

How much do want to apply today’s enlightened ideas to people from long ago generations? In the case of overt racism, such as that displayed by Civil War era leaders in the south, it’s obvious that we should remove any type of special place they hold in history books. The removal of Civil War statues, seen by most as symbols of greatness, is proper. But how far do we go in correcting the errors of the past? Spink’s name was being honored by the award. It makes perfect sense to remove it.

But what do we do with Cap Anson, Rogers Hornsby, Ty Cobb, Eddie Collins, and Tris Speaker? All are honored in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but each of them also has been associated with either deplorable behavior toward minorities, or were associated with racist organizations. Hornsby and Speaker were members of the Ku Klux Klan, Anson barred black players from the major leagues in the 19th century, Collins worked actively to keep African Americans from getting a tryout with the Red Sox when he was their general manager, and Cobb had numerous run-ins with blacks.

But as we’ve seen through the publication of Charles Leerhsen’s book A Terrible Beauty, (and my own biography of Ty Cobb, published in 2004), Cobb’s situation is complicated. The same may be said for Hornsby, Collins, and Speaker, who knows for sure?

Canceling just for the sake of canceling, and erasing names just so we can feel better, isn’t the answer. But in the case of Spink, who used his powerful publication to denounce the notion of integration, the decision to remove his name was wise.

When Spink died in 1962, The Sporting News published a lengthy tribute. It was penned by longtime colleague and friend Carl T. Felker, who worked with Spink for more than three decades. Felker produced thousands of words and outlined the many accomplishments of Spink in detail: the efforts of Spink to help baseball get past the gambling scandals of the 1910s, and his support for minor league baseball, as well as the export of baseball to other countries. Felker outlined Spink’s support for the spread of night baseball and radio to help grow the popularity of the game. He mentioned that The Sporting News published half a million copies of their paper each month during World War II for consumption by servicemen overseas. He mentioned Spink’s tenacious pursuit of truth and accuracy in reporting. But, Felker never once mentioned the integration of baseball, or Spink’s feelings on that seminal issue. In that case, the silence of The Sporting News served to tell us what we needed to know about J.G. Taylor Spink.

Tell me what you think about this issue in the comments section below.