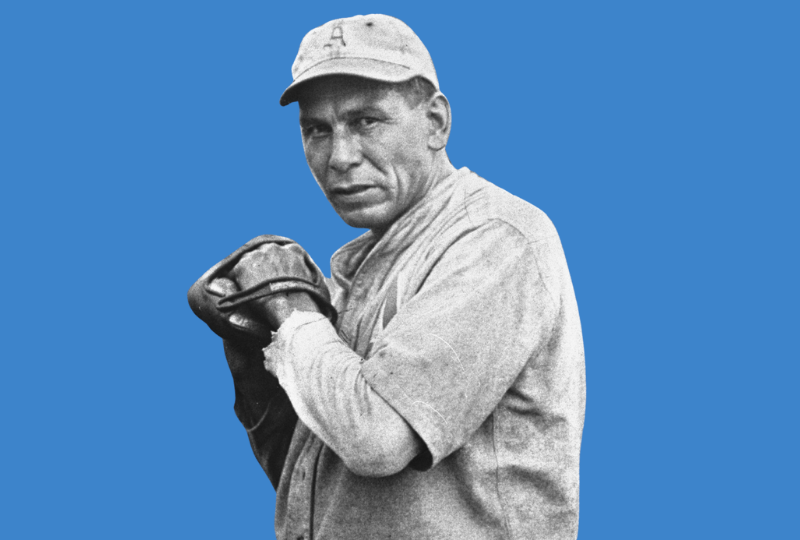

His legendary manager, who spent more than half a century in baseball, called him by his middle name. His mother called him “Charles Albert.” And his teachers and classmates at Carlisle Indian School simply called him “Charley.”

But during his baseball career, where he was so masterful on the mound that he won more than 300 games as a professional, Charles Albert Bender’s teammates referred to him as “Chief.”

The impertinent usage of names like “Chief” stripped the dignity from athletes like Bender. Though they strived to be a credit to baseball in every way: as competitors, as dependable teammates, as gentlemen; still Native Americans were relegated to second (maybe even third)-class status when they were collared with insensitive and racist nicknames.

Most galling as we look back from our time in 2022 to view American more than a century ago, is the pervasive acceptance of such terrible nicknames. The media and fans (indeed society as a whole) were fine with such labels. If an athlete was Native American (common current nomenclature is also “Indigenous Peoples”), then “Chief” was what they were often called.

Other Ballplayers Were Given Racist and Insensitive Names

Just as bad: if an individual had a big nose, large lips, or was dark-complected, they might get an equally dreadful name.

A catcher named Jay Justin Clarke, who apparently had French-Canadian heritage and perhaps some Native American too, was raised in Michigan and had a dark complexion. This led a sportswriter to call him “Nig” Clarke. Over the course of a twenty-year career as a dependable professional catcher that began in 1902, that terrible racist epithet followed Clarke. Even though Jay was born in Canada, in 1917, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps and fought in the First World War for America. He ended up loving the Marines so much that he stayed in the service and requested (and was granted) U.S. citizenship. When he came back to baseball years later, the racist nickname was still used by newspapers and some teammates.

There’s no record of Clarke being a problem for his employers or of having broken the law, but the racial stereotypes of his day still emerged in the pages of The Sporting News, who wrote of Jay’s performance in the Eastern Shore League in 1925:

“Nig Clarke not only led the league with the bat and the mitt and the arm, he was the very picture of a baseball player. I rather suspect that Nig put away as much corn juice as the next man. In the days of his greatness he was wont to take a couple of snifters every morning before breakfast. Never seemed to hurt Nig any.”

Native Americans were drinkers, don’t you know? At least The Sporting News would want to make sure you understood that, even as they gave Clarke a back-handed compliment.

William Ellsworth Hoy, a speedy outfielder from rural Ohio, was born without the ability to hear and attended The Ohio School for the Deaf in Columbus. When he made it to professional baseball in 1886, he was called “Dummy,” though he referred to himself as Billy.

The “accepted practices” of yesteryear can seem brutal to us from our righteous perch in modern times. But it’s complicated, right?

Except it isn’t.

Calling an Indigenous person “Chief” rather than his real name is a way of placing him in a separate, lesser class. It also dishonors the heritage of his people. Referring to a man who cannot speak clearly or hear at all as “Dummy” is uncivil. Calling a man “Nig” or “Blackie” (as Otis Carter and Ralph Schwamb were during their baseball careers), is callous.

Bender and Others Did Not Approve of Racist Nicknames

What must have Charles Bender thought as he was pitching the Philadelphia Athletics to the pennant in 1910 when he won 23 games and a 1.58 ERA with 25 complete games? Or when he helped the A’s to the World Series again in 1911 and 1913, winning a total of five games in the Fall Classic? Did Charles ever really feel like he belonged? Did he feel exploited? Did he simply shrug and accept the fact that in America he would only be seen as an “Indian?”

Maybe Charles Albert Bender actually didn’t mind his nickname? That’s what some have said about the issue. But they are flat wrong.

Bender wanted to be known as a tough pitcher. But he was never happy with the name that shadowed him in baseball.

“I do not want my name to be presented to the public as an Indian, but as a pitcher,” he told Sporting Life in 1905.

However badly Bender must have felt about the racism that was evident in the name used by almost everyone in baseball to describe him, he was valued by the man who wrote his name on the lineup card.

“If I had all the men I’ve ever handled, and I needed to win one game,” Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack said, “Albert would be my man.”

With an array of deceptive pitches and deliveries, Bender, who was a member of the Ojibwe tribe from the Great Plains, flummoxed enemy batters. He pitched in five World Series for Mack, and in 1913 he had his most noteworthy season because of his usefulness. That year, Charles Albert won 21 games and saved 13 more, pitching between his starts in tight spots to assist his team.

Throughout his career and even after, the brilliant right-handed pitcher signed his autograph as “Charles Bender.” If you see a baseball with “Chief Bender” scribbled on it, it’s a forgery.

It’s Time To Change Bender’s Hall of Fame Plaque

Sadly it wasn’t just Bender who suffered the pain of having his name modified. Others, most famously “Chief” Meyers and “Chief” Sockalexis, were strapped with the disparaging name.

Sockalexis was such a talented player for Cleveland that the team changed its named to “Indians” to note his time on their roster. Cleveland held onto that name for more than a century. This year, the franchise plays as the “Guardians” for the first time. Just as bad, the team clung to a racist caricature of Native Americans that they used as a logo for decades. Even today there are some who think the use of such stereotypes are acceptable.

But the conversation about history is widening, and some people are taking action.

Jordann Lankford is the director of Indian Education for All. She explains that it’s crucial to acknowledge the racism and mistakes of the past to educate future generations. “The bottom line is that teaching children how to stereotype groups of people is not good for education,” Lankford says.

Over at the popular Baseball Reference website, the de facto owners of the statistical history of the game on the Internet have made a decision to not display Bender and Meyers and others by their unwanted names. Hoy is listed as “Billy Hoy,” and John Tortes Meyers, a member of the Cahuilla nation, is presented as Jack Meyers, the name the catcher preferred. Clarke, who embraced America even though it wasn’t his native country and fought in a war for a nation where sportswriters called him a vile name, is listed as “Jay Clarke” by Baseball Reference.

“We felt it was important to display the names of those ballplayers the way they referred to themselves, and the way they deserved to be respected,” says Sean Forman, president of Spirts Reference, LLC, which owns and operated the Baseball Reference website.

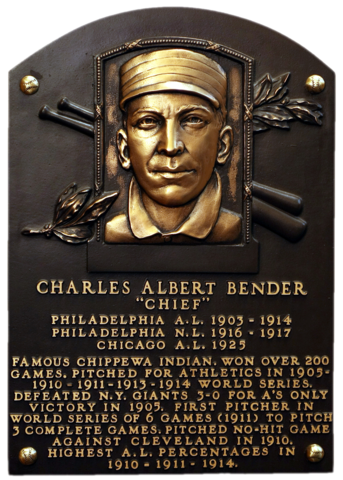

Still, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum lists “Chief” as a nickname on Bender’s plaque. That’s surprising considering the sensitivity the Hall of Fame shows for baseball history. It’s time for the Hall of Fame to change that inscription and strike “Chief” from Bender’s honor in their plaque gallery.

Several years ago the Museum recommissioned plaques for some players, after Bob Feller noted that his plaque made it seem as if he did not have a gap in his baseball career while he served in the U.S. Navy in World War II.

Plaques for Latin players have also been altered to display their surnames in the way that they are traditionally presented in their own cultures. There is a precedent for the folks in Cooperstown to right a wrong.

Given Bender’s desire, which he expressed in his own words, to be known as a pitcher, not as an “Indian,” why does his Hall of Fame plaque begin it’s description of him as a “Famous Chippewa Indian”? Tony Gwynn’s plaque does not lead with ” Famous African American.”

When Bender died in 1954, some things had thankfully changed for the better for Native Americans in the United States, but there was still a lot of prejudice. The Sporting News, which was never a bastion for equality, ran this headline above the former pitcher’s obituary: “Chief Bender Answers Call to Happy Hunting Grounds.” Ugh.

The Hall of Fame’s plaque isn’t that prejudiced or racist. It was created at a time when folks just didn’t see a problem with labeling people with insensitive names. The Museum has excelled at educating its visitors about racism and gender and many issues important to the fabric of America. So, why not also address the glaring problem with the plaque of a great pitcher who would rather have been known as Charles?

We can’t heal the pain that Charles Albert Bender felt when he was called by a name that marginalized him. Bender has been gone for almost seven decades. But we can rightfully honor him and ballplayers by not using the racist and cruel names that were attached to them by a society that was prejudiced against them.