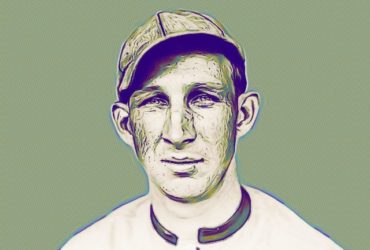

There was always something unusual about Eddie Grant, but he was comfortable with that. He didn’t mind being different.

In a brief life that stretched only 35 years and a few months, Grant accomplished many things: scholar, athlete, lawyer, soldier. He excelled at them all, but ultimately a volley of bullets from a German machine gun ripped apart his belly in a dense forest in France. His body is still buried nearby, a reminder that war extinguishes the bright promise of young men.

Grant played ten seasons in the major leagues for four different clubs, but his favorite stop was in New York where he met his biggest fan. In most ways, John McGraw the exact opposite of the erudite Grant. Where Eddie was well-read, McGraw shunned even the newspaper. Where Grant enjoyed talking about science and politics, McGraw liked to play poker and fight. Where Grant was tall and strapping, McGraw was squat, with a low center of gravity, built like an anvil. But one subject the two men could agree on was baseball. Both “Harvard Eddie” and “Muggsy” loved the game.

By the time Grant became a Giant, his ball playing career was in decline, but McGraw loved his versatility and aggressive nature on the diamond. The New York patriarch employed Grant as a spare infielder from 1913 to 1915, and later listed Eddie as one of his favorites. When he learned that Grant had died in the Great War, McGraw reportedly cried.

Grant was born just south of Boston, in 1883 to an educated father and hard-working family. His dad made sure that Eddie was offered every chance to train his mind, and sent him to the prestigious Dean Academy in Franklin, Massachusetts, which later produced screen star Broderick Crawford and Hall of Fame catcher Charles “Gabby” Hartnett. After Dean Academy, Grant enrolled at Harvard University where he played four sports, excelling in basketball and baseball. While at the university, Grant developed a taste for Latin and physics. Years later he would confound teammates in the dugout by explaining the trajectory of batted balls in Latin.

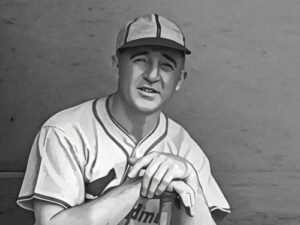

For three years in his early twenties, Grant attended Harvard Law School in the fall and winter and played professional baseball in the spring and summer. It was the perfect marriage of his most passionate interests. In 1906 he was purchased by the Philadelphia Phillies after a scout saw him play in New Jersey. The team convinced Eddie to pursue a career in the game and by 1907 he was in their lineup.

As a big league ballplayer in the early twentieth century, Grant was an oddball. Instead of drinking, carousing after women, and gambling, he liked to stay in his hotel room and read books about Roman law. While his teammates were mostly uneducated men who chewed tobacco and cussed, Grant had a law degree and liked to smoke a pipe while reading books. He was known for tearing pages out of his favorite volumes and stuffing them in the back pocket of his uniform pants. Always interested in proper grammar, Grant’s teammates got used to Eddie’s unique way of calling for a pop fly. Instead of the traditional “I got it,” Grant would holler “I have it.”

Yet, in spite of his uncommon intellect and unusual personality, Grant was well-liked by his teammates. Between the lines he was a competitor and well-skilled. His best talents were bunting and stealing bases. He usually served as the Phillies’ leadoff man or hit in the second spot in the lineup. He handled third base well, sharing the left side of the infield with shortstop Mickey Doolin, who became his best friend on the Phils.

His finest day in the majors came as a member of the Phillies in a doubleheader against McGraw’s Giants in 1909 when he collected seven hits, five of them off the great Christy Mathewson. Grant joked that it was the only five hits he ever got off “Big Six.”

In 1910 the Phillies peddled Grant to Cincinnati where he played for parts of three more seasons before McGraw snatched him in the middle of the 1913 season. By that time, the 30-year old Grant was more a lawyer than a baseball player. He practiced law in the offseason in Boston, but was a part-time player on the diamond. For the Giants, Grant was used at third, second, and short for three years, serving also as McGraw’s “bench coach,” a position the New York skipper created so he could keep a distance from the day-to-day problems that occurred on a team. Grant handled several of the younger players, most notably working with third baseman Milt Stock as well as George “High Pockets” Kelly, who went on to become a Hall of Famer.

Just 32 years old, Grant retired prior to spring training in 1916 to devote his full attention to his law practice. But he was only able to do that for about a year when his life was disrupted after the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. Though he was 33 at the time and would not have been drafted into service, Grant voluntarily enlisted, becoming the first former major leaguer to do so.

The former third baseman served in the 77th Division, graduating from officer’s training as a captain. More mature and educated than many of the other officers in the Army, Grant was a natural leader. He quickly proved himself to be an excellent officer. After several months of training, Grant arrived in France in early 1918 with his division.

Fighting in the Argonne Forest of France in 1918 with the “Statue of Liberty” division, the Harvard graduate distinguished himself as a fine leader and capable soldier. In October, Grant’s division was ordered to rescue the “Lost Battalion” – thousands of soldiers stuck behind enemy lines in the freezing cold without supplies or ammunition. When all of his commanding officers were wounded or killed, Grant was placed in charge of the entire battalion on October 5. Only moments after taking charge of a group of men during a firefight, a German shell exploded almost directly on his location and tore into his body, killing Grant instantly. Two days later the Americans broke through and rescued the remaining members of the Lost Battalion. One month later, the armistice was signed and the war was over. Grant had died only 44 days before the war ended.

Major Charles Whittlesey, who was commanding the Lost Battalion, said, “When that shell burst and killed that boy, America lost one of the finest types of manhood I have ever known.”

Grant’s remains were buried under the frozen ground of the Argonne Forest where he fell, but were transferred to a military cemetery later. His headstone is still there today in France.

Grant was just one of about 175,000 Americans who died in the first World War. But he was only one of six professional baseball players who were killed in action. His death hit McGraw hard, and a few years later, with the help of funding from a civic group, a plaque was installed at the Polo Grounds in New York to honor Grant. The plaque read in part: “Soldier, Scholar, Athlete, Killed in Action, Argonne Forest, October 5, 1918”. At the ceremony, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis said: “Edward Leslie Grant gave his all not for glory, not for fame, but just for his country…. His memory will live as long as our game may last.”

Every year on Memorial Day as long as John McGraw was in charge of the Giants, flowers were placed on that plaque at the Polo Grounds in memory of one of his favorites, the American hero, Eddie Grant.