From ugly ducklings to elegant swans: the Mets made such a quick transformation after being record-setting losers as an expansion franchise. In just their eighth season, the Mets shocked baseball by winning the World Series. That’s why the 1969 team is still the most popular in team history, and known as “The Miracle Mets.”

The Mets have made five trips to the World Series, and one thread connected all of those teams: great pitching. Many of those hurlers are on this list, which comprises the 20 players in Mets history with the most Wins Above Replacement.

Only McNeil and José Reyes have won a batting title for the Mets. Both sat out all or part of the final game of the season to preserve their batting crown, McNeil in 2022, and Reyes in 2011.

Stearns was intense. He played defensive back for the University of Colorado and still holds the school record with 16 interceptions in one season. The Phillies drafted him second overall in the 1973 draft. Stearns was in the big leagues the following year and got a pinch-hit single in his first at-bat. But his path was blocked by Bob Boone and the Phillies packaged Stearns in a trade with the Mets that brought Tug McGraw to Philadelphia.

Stearns backed up veteran Jerry Grote for a few seasons before taking over as the starter. At one point he became so frustrated that he asked the Mets to send him to Tidewater so he could play regularly. He was selected for the All-Star team four times as a Met and his tough style of play made him a fan favorite.

Stearns averaged 18 steals per season, which trails only Roger Bresnahan among catchers, who played in an era when everyone, no matter how nimble, stole bases.

Cone was a flake, but he was intense on the field, and loose off of it. The Royals traded him because they thought he was uncoachable. He was a master prankster on par with contemporary Greg Maddux.

Cone threw his curve and slider “backwards,” meaning he held the pitches the opposite way from most pitchers. “I feel that it gave me kind of an unusual break on my pitches,” Cone said, “a lot of guys [put] all of the pressure on their middle finger. I put a lot of pressure on my index finger when I threw my breaking ball. Most coaches teach just the opposite. To them, the index finger is more of a guide, or just in the way.

“My index finger was on a seam, and that was important to me. I could sweep it a little more that way, I could get a little more side-to-side break, and then, if I wanted to get on top of it, I could make it break down a little more. I also felt that I could control the pitch better that way.” Cone also used pine tar to help him grip his curveball, which he hid on his belt buckle.

The 1986 Mets are one of the best teams in baseball history, but their roster was filled with drunks, jackasses, and drug addicts. They were almost certainly the most hated team of the last 40 years, with the possible exception of the modern Astros, who are gaining fast in the competition of most loathed.

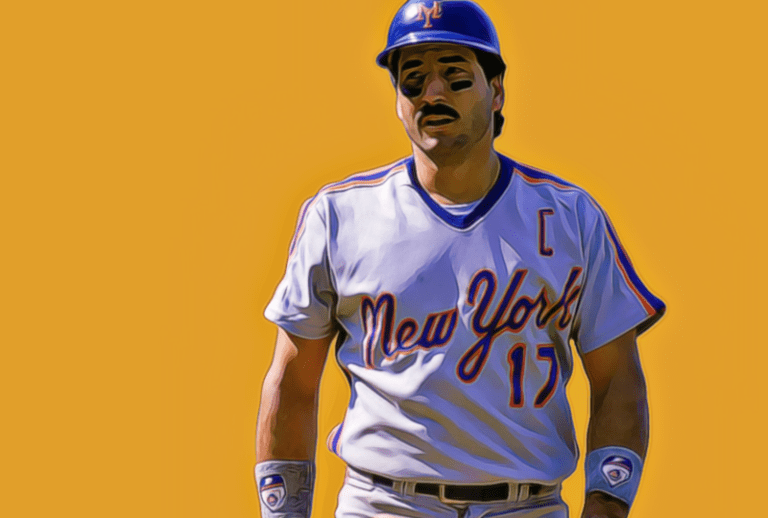

Mookie Wilson stood out like a rose among the weeds on the Mets. He stayed away from alcohol, he didn’t chase women, and on road trips he stayed in his hotel room, preferring a book or a TV show to carousing. Wilson was also a great teammate and a leader, a product of the farm system who dedicated himself to representing the Mets with dignity, even though all around him were fart jokes, extramarital shenanigans, and lines of cocaine. Everyone loved Mookie.

In 1986, Wilson started the season on the disabled list due to a freak injury. After a workout that was shortened by a rainstorm, Mets’ coach Frank Howard insisted on reusing baseballs that had been drenched. He tossed a bucket of the wet balls into a dryer in the clubhouse. Later, Mookie tossed the water-logged baseballs from the outfield. “It was like a shot put,” Wilson said. After the workout with the heavy baseballs, Mookie felt pain in his right shoulder. He came back a few weeks into the season, but Wilson’s arm was never the same. Howard’s folly didn’t impact Wilson’s legs: he stole 20 bases in a season eight times. In the 1986 World Series, Mookie swiped three bags

Two of Mookie’s brothers also played professional baseball, and his nephew made it to the major leagues. After his playing career, Mookie became an ordained minister, and he and members of his family released a gospel album.

Three different managers accused HoJo of corking his bat: Roger Craig, Whitey Herzog, and Hal Lanier, all during MLB’s Home Run Explosion of 1987. That season home runs increased by 17 percent. Johnson denied wrongdoing.

“My ability is being challenged,” Johnson told reporters after Craig asked an umpire to confiscate Johnson’s bat during a game between the Mets and Giants in 1987. “I’m hitting home runs fair and square, the right way.” Over the years as he continued to be among home run leaders, Johnson would at times act coy, teasing reporters as to whether he used a corked bat or not. Many years later, when asked about HoJo’s power surge, Davey Johnson said, “Did he probably cork his bat? Yes.”

Had a bigger impact on his team’s than Gary Carter did as a Met. Piazza never won a title, but he became more beloved in New York, more so than Carter, who was seen as phony. New York doesn’t like wholesome players, and Carter was too Wheaties box wholesome for the Big Apple. Piazza was always in some sort of controversy. And he could rake, of course.

Leiter was 60-53 when he became a Met at the age of 32. He won 85 games in seven seasons with New York, and spent zero days on the disabled list. He didn’t touch 92 miles per hour on a good night, but Leiter was a thinking-man’s hurler with a wicked hard curve.

“I won’t say that women belong in the kitchen, but they don’t belong in the dugout.” — Keith Hernandez

“Well so what. I mean you played first base. I mean they always put the worst player on first base. That’s where they put me and I stunk.” — Elaine Benes to Keith Hernandez in an episode of “Seinfeld”

Reyes is clearly the best shortstop in the history of the New York Mets, finishing with more than 1,500 hits, 100 homers, and 400 stolen bases with the team. For decades the Mets had a problem finding a great third baseman, until David Wright solved that. But the franchise also had troubles at short, usually settling on good-field, no-hit guys until Reyes came along.

One of the many members of the 1986 Mets on this list, and probably the most underrated.

Try to keep track of this: Alfonzo’s older brother Edgar Jr. played professional baseball for 12 years, some of those seasons in the Mets organization, but never advanced beyond the minor leagues; another brother Roberto played briefly in the Mets farm system in the early 1990s; a nephew, also named Edgar, played in the minor leagues (you guessed it, with the Mets); and a second nephew named Giovanny was still playing independent ball as of 2022 (after years in the Mets minor league chain. In 2017, Edgardo’s oldest son Daniel was drafted by the Mets in the 38th round, basically as a favor. In case you’re scoring at home, that’s six Alfonzo’s who have been in the Mets system.

Beltrán was a great teammate, a strong leader, and immensely talented. He was hired to manage the Mets one year after his retirement as a player, though he never managed a game because of his central role in The Great Houston Sign-Stealing Scandal. Prior to that mess, Beltrán had been highly respected in the game, almost regal. He was sort of like the Mariano Rivera of the outfield. But the sign-stealing fiasco has washed away his patina.

“If Darryl works hard, if Darryl has a professional attitude in his work habits, he can be one of the all-time greats in this game. And if he doesn’t, if he just goes through the motions and does enough work to get by, he’ll be just another great player.” — teammate John Stearns on Rookie of the Year Darryl Strawberry

How prescient Stearns was. The final ledger shows Strawberry as a great player for a few years, but never the legend to match his insane talent. For too many years he was lazy, selfish, and distracted by the rock star life in New York. As a result, he is one of those guys, like his childhood friend Eric Davis, who watches lesser talented players inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Koosman had fantastic control, kept the ball low, and had lots of movement on his pitches. He was a strong farm boy from Minnesota with long arms. He was drafted into the Army out of high school and got even stronger. His luck turned when he was stationed in El Paso where he was spotted by a fellow soldier whose uncle was an usher at Shea Stadium. The soldier called his uncle and urged the Mets to get someone down to Texas to see the tall left-hander everyone called “Kooz.” By 1968 the 25-year old Koosman was in the Mets rotation, where he won 19 games and finished second to Johnny Bench in NL Rookie of the Year voting.

In 2018, deGrom had eight games where he pitched at least seven innings and allowed one earned run or less and failed to get the win. Only once since 1916 has a pitcher exceeded that number in a single season: Roger Craig, also with the Mets, in 1963. Through 215 career starts as of the end of the 2023 season, deGrom has 23 such games on his ledger. It’s gotten to the point where he gets so little run support and so many hard-luck no-decisions, that these games are now called a “deGrom.”

The troubles that derailed Gooden’s career were not inevitable, and if he debuted in 2004 instead of 1984, it’s a good bet he wouldn’t have spiraled out of control. Success came quickly to Gooden because he was a once-in-a-generation talent, like Bob Feller. Gooden never had the support system he needed to handle fame. The Mets were ill-equipped to help their prodigy, the clubhouse was packed with drug addicts and alcoholics. The front office was oblivious, and manager Davey Johnson kept a distance from his players, preferring to “treat them like men” rather than dish out discipline. If Gooden had come up with the Dodgers or the Cardinals, I don’t think he could have disappeared for days between starts on cocaine-binges, or arrived moments before a game and been allowed to give a flimsy excuse. Those organizations would have assigned someone to keep tabs on him. The Mets asked Darryl Strawberry to babysit Gooden, which is like asking a grizzly bear to tend to your picnic basket.

Baseball doesn’t have sad stories like Gooden’s any more, thankfully. Systems are in place, from the labor unions, even in the minor leagues, to shelter a player from going too far off the rails. Gooden’s troubles came during the last generation that allowed ballplayers to go one thousand miles per hour in pursuit of fun. That system failed Darrell Porter, Bob Welch, and it failed Dennis Eckersley for a while. It helped pull Gooden away from greatness and deeper toward hell. Gooden was as talented as Feller, he was more talented than Nolan Ryan, and he was a better pitcher than 60 or 70 guys on this list, but he fell prey to his demons and missed a chance to take his place with the legends of the game. In some ways, his sad story helped baseball fix their house and address issues they never had before, which is the one good thing that comes out of the Gooden narrative.

Wright is probably the most popular position player to ever suit up for the Mets. It’s either him or Keith Hernandez, or possibly Mike Piazza. But I’d put my money on Wright, who spent his entire career with the team. He was much more likable than those other two guys.

The former Southern Cal star was a physically mature big league pitcher from his first start for the Mets when he was 22 years old. He had a once-in-a-generation arm. He was built like a tree stump, supported by powerful legs. In his third start Seaver pitched a ten-inning four-hitter against the Cubs at Wrigley Field. The New York spotlight was perfect for him, the team was woeful, expectations were low, every fourth day all eyes were on him. He was “Tom Terrific.”

It’s easy to forget how hard Seaver could throw his fastball. In the 1967 All-Star Game, amped up in his first appearance in a midsummer classic, Seaver threw so hard that he bruised the left hand of his catcher, Tim McCarver of the Cardinals. “For two weeks after that game,” McCarver said, “I couldn’t wrap my pinky around the bat.”

In 1969, Seaver was remarkable. He started 35 games, and in 24 of them he allowed zero, one, or two runs. He won 25 games, threw five shutouts, and got better as the season drew to a close. Seaver went 7-0 after August 31st with seven complete games, three shutouts, a 0.71 ERA, and did not allow a home run. He pitched ten innings in his Game Four victory in the World Series, helping the “miracle” become reality for the Mets.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.