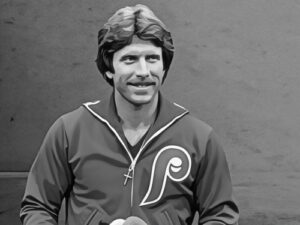

Gary Sheffield never cared much what people thought of him. Now, that may be backfiring on the former All-Star slugger. In the latest results of the Baseball Hall of Fame voting by the writers, Sheffield fell shy of gaining election in the 10th and final time his name will be on that ballot.

On Tuesday, Sheffield received a vote on 63.9% of the ballots submitted by members of the BBWAA. That falls well shy of the 75% required for election.

After missing out in what was his best chance to earn a plaque in Cooperstown, Sheffield will need to garner enough consensus among a smaller, often more stingy group: the Hall of Fame special election committee.

Sheffield’s raw credentials are impressive: 509 home runs; 2,689 hits; a career .292 batting average: 1,636 RBI, and a 907 OPS. He won awards too: five Silver Slugger Awards and a batting title. He was a World Series champion in 1997 with the Florida Marlins. And he hit everywhere he played: 35+ home run seasons with four different franchises, and 30+ HR seasons with five.

But Sheffield’s travels, his suspect attitude, and his poor choice of friends have defined his legacy. One could honestly say he was as one of the 2-3 best righthanded hitters of his generation, but Sheffield will likely always be on the outside of the Hall of Fame. Why did Sheffield fall short of election by the baseball writers? What are his chances to get in via the special election committees in the future?

RELATED: Gary Sheffield Player Page

The Me-First Player

How talented was Gary Sheffield? When he debuted with the Milwaukee Brewers in the late 1980s, he was such a great player the team moved future Hall of Famer Paul Molitor out of position to make room for the young infielder in their lineup. At that time, Sheffield was a 19-year old shortstop. 19-year old’s don’t play shortstop in the major leagues. It’s happened about four times. But Sheffield, a nephew of All-Star pitcher Dwight Gooden, had the pedigree and the experience at a young age to be a teenage star. The Brewers realized Gary wasn’t consistent enough in the field to play short, so they shifted him to the hot corner, supplanting Molitor, a career .300 hitter.

But Sheffield’s maturity was evident from the first day he stepped on a major league diamond. He sulked when he wasn’t placed high in the batting order. He bristled when fans booed his miscues in the field. He brooded when he struck out. He was surly with reporters, his manager, and teammates.

At one point in his Milwaukee days, young Sheffield admitted to throwing baseballs into the crowd (making errors on purpose) because of his frustration with his team and the fans. He was traded for the first of man (many) times during spring training in 1992. He hit 33 home runs in his first season with his new team (the Padres), but that was just the first of many “new teams” for Shef.

Throughout his career, Sheffield was cantankerous. It didn’t seem to matter where or for whom he played, a change of uniform never seemed to satisfy Sheffield. He seemed to only be interested in his contract and his own numbers. At least that’s how it seemed to the outside world based on Sheffield’s actions.

Ol’ Suitcase Sheffield

Great players who bounce from team to team usually face a difficult time establishing a legacy. After he was jettisoned by the Brewers, Sheffield played for seven teams. In his last four seasons he managed to hit 60 home runs, but he played for three teams. Twice he was traded midseason, and his tenures were often brief. Sheffield only managed to play as many as 500 games for the Marlins and Dodgers.

With his suitcase in hand, Sheffield served as a “bat for hire” for the balance of his career. He kept producing: he’s the only player to finish in the top ten in MVP voting with five different teams.

Yet every time he planted himself in a new place, Sheffield’s roots didn’t really take to the soil. That’s because he was a high-priced player who didn’t really have a defensive position, and he frequently griped. During one of his most difficult professional stretches, Sheffield forged a friendship with arguably the worst person in the game.

Friends in low places

They say “misery loves company,” and for Sheffield that maxim was exhibited through his friendship with Barry Bonds. Their relationship ended up costing Sheffield, and he may still be paying that tab to this day.

The “bromance” between Sheffield and Bonds makes sense: both were moody superstars who emerged in the 1990s; both had difficulties with teammates and held contempt for the media; and both had giant chips on their shoulder. Those issues alone are not enough to indict anyone. Ty Cobb had his faults, and so did Ted Williams. Even Babe Ruth was flawed (teammates once watched with delight as the Babe was chased through a train by a woman with a knife after Ruth had allegedly inflicted her with a sexually transmitted disease). Our heroes are not always heroic.

But, Bonds introduced Sheffield to Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO), a lab in northern California that operated at the center of the steroid craze that inflicted MLB in the 1990s. Whether intentional or not, Sheffield secured a batch of drugs from BALCO in the early 2000s, a fact that was later revealed during testimony in front of the U.S. Congress.

While Sheffield has been candid about his “gym” friendship with Bonds, as well as the reasons he bought steroids, his indiscretion has hounded him. Many writers, for many years penalized Shef for the incident.

Even though the cloud of the steroid purchase has cleared a bit above Sheffield’s head in recent years, his support for Cooperstown has only limped forward, like a bum knee.

Will Sheffield ever be elected to the Hall of Fame?

The Baseball Hall of Fame changes its special elections process more often than a nervous teenage girl changes outfits before a date. Just when you think you understand the rules for getting into the Hall of Fame, the folks in Cooperstown have a meeting and flip it.

Currently, a 16-person committee meets every few years to evaluate eligible players retired at least 16 years prior. Those voting committees are carved into special “eras” that examine players (and managers) from certain time periods. Sheffield will be eligible for a ballot through one of those committees in December 2025 for players who did most of their playing after 1980. At that time he’ll likely be on a ballot with Albert Belle, Don Mattingly, and a group of controversial candidates that includes Bonds, Roger Clemens, Rafael Palmeiro, and Curt Schilling.

Last time a group of players was considered by the contemporary era committee, only Fred McGriff was elected. I don’t have to tell you how different McGriff’s image was than Sheffield’s.

It’s unlikely that Gary Sheffield will ever get 12 people out of 16 on a closed-room committee to throw him support. His case is similar in merit to that of Belle or Dick Allen, both dangerous righthanded power hitters. But neither of them have steroid charges against them. And neither have garnered enough votes.

The Shef can make the menu, he can heat the skillet, but in the case of this ballplayer, his dinner will likely always be cold. It’s no Hall of Fame for you, Gary.