When baseball fans discuss the most famous home runs in the history of the game, they frequently mention the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World”, Bobby Thomson‘s classic knock off of a weary Ralph Branca in a special playoff in 1951.

A lot of noise is made about Thomson’s homer because it won the pennant, and because of the reports that the New York Giants had stolen signals from opposing teams in the second half of the ’51 season. These rumors started circulating in the winter of ’51, so they are hardly new, but in this century, the rumors were given the official stamp of truth by The Wall Street Journal. The fact that the Giants had stolen signs means very little (this happens in every inning of every game…and if it doesn’t, it isn’t for a lack of trying). The sign-stealing probably didn’t help the Giants much, either, but folks like a bit of intrigue.

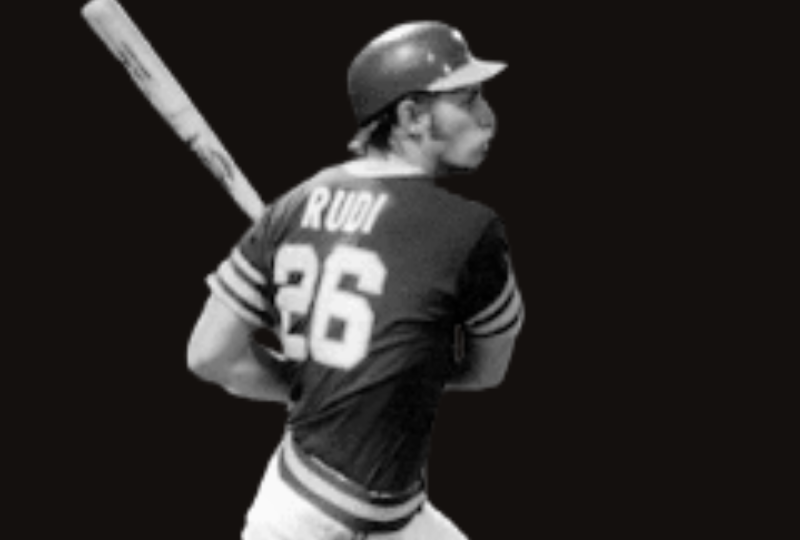

This year marks the anniversary of another home run. That’s right: this year marks the 50th Anniversary of Joe Rudi‘s Genius Home Run of 1974. What? You’ve never heard of it?

True, Rudi’s homer doesn’t quite measure up to the famous Branca/Thompson saga, but it hasn’t been told 1,000 times. And while the ’51 Giants had an amazing mechanism for stealing signs–telescopes, electronic buzzers–Joe Rudi had nothing more than old-fashioned country know-how.

The ’74 Series matched up the two best team ERAs in the majors (Oakland’s minuscule 2.95 just barely ducking under L.A.’s limbo-low mark of 2.97), and each pitching staff would toast a Cy Young winner at their fall awards banquet. Jim Hunter‘s 25-12 record, with a 2.49 ERA took the award in the AL, while Dodger fireman Mike Marshall‘s 15-12, 2.44 (including 21 saves in a league leading 106 appearances) brought him the award in the NL.

As expected, the games were tight: the pitching lived up to billing, while the hitters struggled to a combined average of .220. Only once did either team manage to score more than three runs in a game. The Athletics scratched ahead to a lead of three games to one, with only one of the games being decided by more than a single run. Each team’s ace starter/reliever combination (Hunter and Rollie Fingers for the A’s; Don Sutton and Marshall for the Dodgers) dominated whenever they entered the picture-and the rest was a close fought battle, tight in the corners and in the clinches. As we know from experience, such a tense, balanced series can turn on the smallest play-a blown call, an unlikely error.

In this series, the pivotal play occurred in Game Five. By the bottom of the seventh, the score stood tied at 2 apiece, and the series hung in the balance. The A’s had scored once in the first on an error and a sac fly, and again on a Ray Fosse homer; the Dodger’s pieced together two runs to tie in the sixth, on a pinch double, a walk, a sacrifice bunt, a fly ball, and a single. And there the score remained.

By the seventh inning Tommy Lasorda had called for Marshall, in relief of Sutton. This is the duo that grabbed game two for the Dodgers, and the way Marshall had looked throughout the series, it was easy to imagine them repeating the trick. His strikeouts to walks ratio (10 to 1) in the series meant Oakland would have to earn every base, something no one did much of against Marshall all year. In the NLCS, the Pirates didn’t score once off Marshall, and so far the A’s had come up dry, too.

Here’s where the intrigue comes in: Just before the beginning of the seventh, Dodger left-fielder Bill Buckner was greeted with a shower of bottles and trash (by now it can be said: the World Series has not been kind to Buckner), and the game was delayed for several minutes. During the long pause the lead-off hitter, Joe Rudi, watched while the field crew cleaned up and the P.A. announcer did his best to calm the, um…bound up…Athletic supporters. Rudi wasn’t watching the nonsense in the outfield during this unexpected intermission; he was watching Marshall, and he noticed that Marshall did not keep warm during the delay. Marshall did not make one toss, to the plate, or around the infield. And so, Rudi put two and two together. He reckoned that Marshall could not come with his hammer curve, nor could he risk his late breaking slider. Not without the feel for it. No, Marshall wasn’t out there, keeping warm, keeping loose–Marshall was out there meditating, gearing up.

He was going to come with straight gas.

Joe Rudi guessed, and he guessed right: fastball all the way…and he parked Mr. Cy Young’s very first pitch somewhere amongst the not-yet-thrown bottles under the feet of the suddenly approving left-field-bleacher fans. That was it. Rollie Fingers came on, held the fort for two innings, and twenty minutes later Joe Rudi was hollering and running around a clubhouse, champagne dripping from his ears.