Tucked away in the corner of the home dugout of Tiger Stadium, a Detroit City police officer spent nine innings with a towel wrapped around his head during a game in 1976. Had he not, his ears would have rung from the chirping that came from behind him. It wasn’t a bird, but The Bird that chirped incessantly, relentlessly, and LOUDLY throughout the ballgame.

Mark “The Bird” Fidrych had the day off from pitching, but his famous beak didn’t.

Dynamic Fan-Favorite with Contagious Enthusiasm

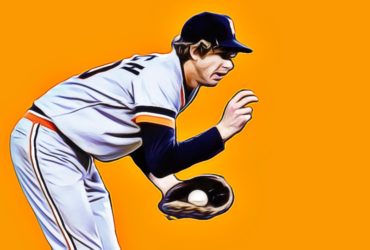

When Fidrych, a 21-year old rookie in 1976, was on the mound, he was the center of attention. He couldn’t help but be. The spotlight found him, and it was for the simplest of reasons. He was himself. Refreshingly so, with enthusiasm and a love for the game.

Back in April, before he captivated the city and ultimately the entire baseball world, Fidrych made his big league debut without expectation, without fanfare. He was just another hard-throwing right-hander, a gangly kid from New England who said things like “Pahk yuh cah in the yahd.“ He was a late addition to the roster out of spring training, a new face on an aging team that had collapsed the previous season on the way to 102 losses, including an embarrassing 19 in a row.

It was nearly a month before he made his first start, facing the Indians at Tiger Stadium on a Saturday afternoon in front of less than 15,000 fans. Less than two hours later, Fidrych was finished, having tossed nine nearly perfect innings. He set down the first 14 batters he faced before issuing a walk, and took a no-hitter into the 7th inning, before surrendering a pair of scratch singles. A groundout, a strikeout, and a flyball later, he was out of the inning, nursing a 2-1 lead. Four groundouts and a pair of strikeouts followed in the 8th and 9th, and that was it. The rookie had his first victory, a complete game two-hitter. It was the first of his league-leading 24 complete games. An unheard of total for a rookie hurler.

He quickly became “The Bird” in large part because of his slender build (his knees almost popped out of his uniform pants, stork-like) and curly blonde locks. Less than two months later Fidrych had a 9-1 record, and adoring female fans were bribing his barber for strands of his famous mane. He was big-time. There was the cover of Time Magazine and Sports Illustrated. There was an appearance on the Donny & Marie Show and Flip Wilson. At least two biographies were published mid-season. There was the City of Detroit passing a resolution recommending that the Tigers give Fidrych a pay raise. Five years before Fernanado Valenzuela spawned Fernandomania in Los Angeles, there was Birdmania in Motown.

And there were fannies in the seats. Lots of fannies.

Fans Flocked to see Fidrych on the Mound

There’s no evidence that Tigers General Manager Jim Campbell made an effort to pitch Fidrych at Tiger Stadium as much as possible, but during one 13-start stretch at the peak of The Summer of The Bird, the right-hander made 10 starts at the Corner of Michigan and Trumbull and just three on the road. Draw your own conclusions.

Opposing teams salivated at the opportunity to have The Bird on the mound in their ballparks. In Cleveland, where they normally drew about 10,000 fans, 37,000 showed up for The Bird in July. More than 30,000 flocked to see Fidrych and the Tigers in Minnesota. Even in The Bronx, home of the Yankees, Fidrych was a draw. Oakland, which finished 11th in the 12-team league in attendance, drew more fans to see The Bird than they did for a three-game series the previous week.

Why did fans around the country clamor for The Bird? It was his refreshing antics, something rarely seen on a diamond before or since. When The Bird was between the lines, it was a Show. He didn’t take the mound, he pranced on it. He didn’t have a pitching motion, he had a rhythmic, almost hypnotic ritual. Dipping his shoulders toward the ground, bending, leaning, bobbing and weaving as he addressed the plate. And he spoke. He talked – was it to the baseball? Was he telling it where to go? What was this Harpo of the hill up to? Did he have a special relationship with the magical sphere? It seemed he did. He waved his hands in the air, gesturing the ball toward the plate, coaxing it to do his bidding. And it did. He fired 94-mile-an-hour fastballs at the knees like lasers. He carved the corners of the plate. Opposing batters shook their heads, trudged back to their bench, and wondered what had just happened. The Bird fired a four-hitter, two five-hitters. He pitched an 11-inning shutout. 11 innings!

It didn’t seem to matter who was at bat, in fact he didn’t notice, and rarely even knew who they were. He was playing catch. He was hurtling the baseball toward the catcher’s mitt, firing it to a target that he was intensely focused on. The manner in which he pitched – the talking (which was never TO the ball, but rather a dialogue for himself, to help him stay focused on his mechanics), the gesturing, the handshaking of his teammates after they made a fine play behind him, the tossing balls out of play which had resulted in a hit, because they needed to “learn to be an out” – it was never contrived. It wasn’t for the cameras, it wasn’t to get his name on billboards. It was mop-haired Markie Fidrych, the funny looking bundle of energy from Massachusetts who knew only one way to play baseball. And the people loved it.

He started the All-Star Game. He defeated the New York Yankees on national television on Monday Night Baseball, earning praise from the curmudgeon Howard Cosell. In August, Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles went to the plate and talked to his bat, trying to psych out The Bird. Fidrych laughed, smiled that famous, infectious smile, put his arms out in a “I can’t believe it” manner, and proceeded to strike Nettles out with another knee-high heater.

He won 19 games, led the league in ERA and complete games, and won the AL Rookie of the Year Award easily. He finished second in the Cy Young Award voting and 11th in MVP voting despite playing for a team that was hopelessly out of contention. None of the attention fazed him. He wore ragged blue jeans, drove a rusty pickup, and drank cheap beer.

The Injury that grounded The Bird

The following spring he was still Mark, still that character, care-free and youthful. He was playing around in the outfield during spring training, shagging flies with his teammates. A ball sailed toward him and The Bird leaped in the air in a futile attempt to snare it. But he wasn’t a bird, and he didn’t have wings – he couldn’t fly. When he landed, he wrenched his knee. He continued to pitch, and with that bum knee, he altered his motion, tearing the muscle. But he didn’t know that then, no one did. He started the ‘77 season with two losses, then strung together six Bird-like victories: crisp, two-hour games with plenty of knee-high fastballs, cheering fans, and antics on the mound. He was named to the All-Star team for a second time, but by July his wing was dead.

He was never an effective big league pitcher again. He was always “attempting a comeback” or “poised to return.“ He was still “The Bird” when he pitched, but it wasn’t as glamorous when he couldn’t win like he had in the Summer of 1976. It wasn’t until the mid-1980s, after he had been released by the Tigers and failed in a comeback with his hometown Red Sox, that doctors (with new technology) recognized the severity of the damage to his famous right arm. The rotator cuff was nearly torn clean through. But by that time he was a truck driver, a farmer, a former ballplayer.

And that’s the way Mark Fidrych spent his years after baseball, and that’s the way he died on Monday. It’s tempting to see his end as tragic. But Mark Fidrych stopped being tragic decades ago, when the failed promise of his fantastic start was exceeded by that amazing rookie season. He played baseball the way he lived life – with a genuine heart and carefree abandon. He lived his post-baseball life the exact same way. His death is sad, but The Bird will always be remembered for his breath of fresh air back in the Summer of 1976.