This is part of a series on the greatest players in the history of a franchise based on the advanced statistic called WAR (Wins Above Replacement).

First a note on three players you probably expected to see on this list, but who are not. Paul Konerko ranks 21st, Carlton Fisk ranks 22nd, and Shoeless Joe Jackson ranks 23rd all-time in WAR with the Chicago White Sox. But, Jackson also conspired to throw a World Series, so we don’t want to see him here anyway, do we?

20. Chris Sale

A taller Lefty Grove or a shorter Randy Johnson, if you will. Sale isn’t the measure of those two all-time greats, but he is adding to his accomplishments as he enters his thirties with his second Sox team.

Picking up on the comparison to Grove: before a start at home in Chicago for the Pale Hose, Sale tried on the 1976 throwback White Sox uniforms the team was planning to wear that day. Those uniforms were the brainchild of former Sox owner Bill Veeck, a sort of pajama outfit with untucked jerseys and wide lapel collars. Sale explained to team officials that the uniform was uncomfortable and asked that the team not be required to wear them. When he was informed that the uniforms must be worn, Sale flipped out and destroyed the uniforms. He took a knife and cut up every uniform in the clubhouse. The team was understandably shocked and Sale was immediately told to go home. Confused fans booed when his replacement was introduced on the field, the word quickly spread, and Sale’s slasher incident became legendary.

Flash back to a start by Grove in 1931 when things were not going well for the lefthander. Grove loaded the bases and watched all three runners scamper home after an error by one of his outfielders. A walk and a hit later, and Connie Mack bent his bony finger toward the mound to signal a pitching change (Mack rarely walked to the mound to change pitchers). Grove was unaccustomed to poor outings and hated losing. As he walked toward the dugout, the pitcher ripped off his jersey, popping the buttons as he went, then tore off his cap, destroying it and tossing it aside. The fans in Philadelphia hooted at the display, and Grove left the ballpark in his pants, cleats and undershirt.

19. Thornton Lee

At 6’3 and more than 220 pounds in his prime, Lee was unusually large for his era. He grew big and strong under the tall trees of northern California, and later attended California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. He was BMOC (BUSY Man on Campus), playing basketball, and starring as a flanker on the football team. He also threw discus, javelin, and shot put for the Cal Poly track team. But Lee caught the attention of a scout from the San Francisco Seals after he struck out 19 batters. The Seals signed him for $1,500 (about $20,000 in 2020 money).

It took Lee a long time to get a spot in a rotation in the major leagues. He spent parts of six seasons in the minors before he was acquired by the Indians. But Cleveland in the 1930s was a boneheaded franchise, and Lee never found an ally in management. He started 36 games in four seasons with the Indians before they grew frustrated with his lack of control and traded him to the White Sox.

Lee whipped his arm from behind his body in a three-quarter sidearm delivery on his fastball, using his long legs and arms to extend his reach so much that some hitters felt that he was on top of them. Walter Johnson, briefly his manager in Cleveland, praised Lee’s fastball and sharp overhand breaking pitch. In Chicago he was introduced to coach Muddy Ruel, a former catcher. Ruel made adjustments in Lee’s delivery and before long the big lefty was throwing more strikes. He was an All-Star in 1941 when he won 22 games and led the AL in earned run average and complete games. By that time the late-bloomer was 34 years old but only in his fifth full season as a starter.

Lee probably tore his rotator cuff in 1942, but they didn’t have a way of knowing that back then. He tried to regain his form after that, but outside of a four-month stretch in 1945, he was never again effective or pain free. He retired with 117 wins but stayed in the game, scouting until he was 80 years old.

18. Fielder Jones

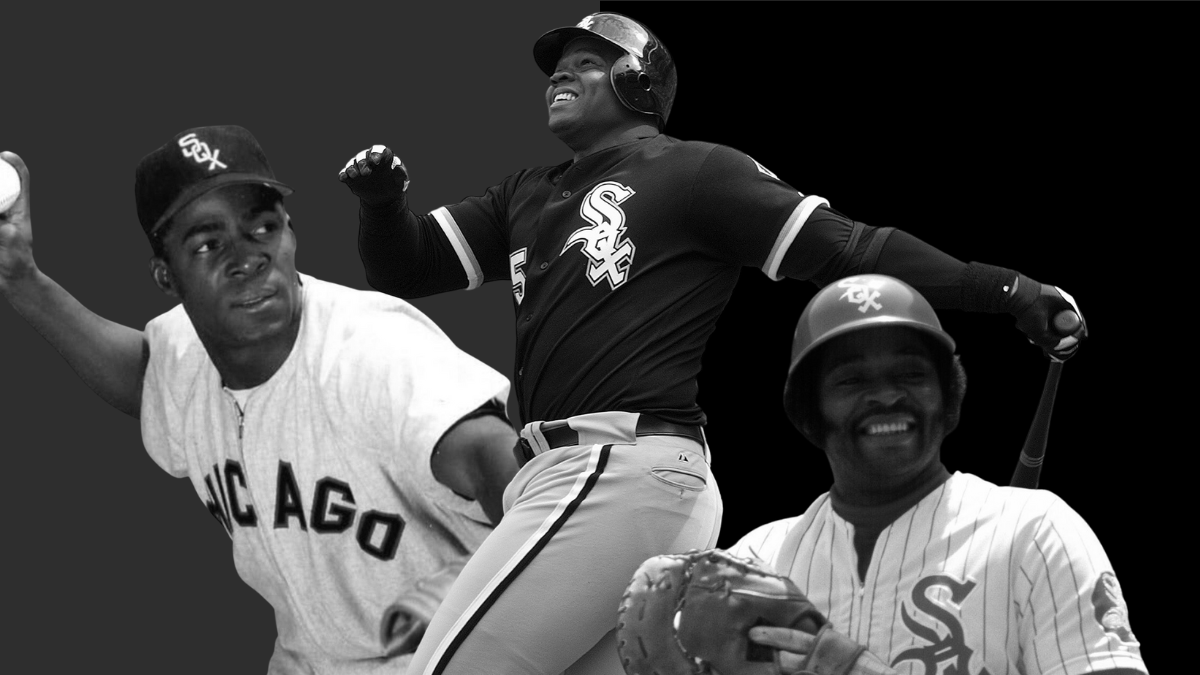

The four most important men in the history of the White Sox are Charles Comiskey, Minnie Minoso, Frank Thomas, and Fielder Allison Jones, the field general for one of baseball’s most inspiring teams.

The 1906 White Sox were all-world on the pitchers’ mound, but less than ordinary at the plate. They were one of the oldest teams in the league, hit only seven home runs all season, and averaged about one extra-base hit per game. The newspapers called them “The Hitless Wonders.” And that was the Chicago papers.

Jones was the manager and center fielder. He didn’t like to walk from his position to the mound: his pitchers finished three out of every four games they started. The Sox’ team ERA was 2.13, and they boasted rugged hurlers Big Ed Walsh, Yip Owen, Doc White, and Nick Altrock, a foursome that won 77 of their 93 games.

The Wonders had a food defense, not a great one, but good. They committed the second-fewest errors in the league, but it didn’t matter with that superb pitching staff because the opposition didn’t hit a lot of balls hard. The best position player on the club was shortstop George Davis, who at 35 was having the last great season of his illustrious career.

In the World Series, the ChiSox squared off against cross-town rival, the Chicago Cubs, and wouldn’t you know it: the Cubs were one of the most successful teams in baseball history. The Cubs won 116 games and were overwhelming favorites in the Fall Classic.

But the Sox scored when they needed to, they even pushed 16 runs across the plate in the final two games. Walsh won two games in three days and White defeated the Cubs in Game Six to finish them off.

Jones had high cheekbones and one of those upside-down smiles. His head was blanketed in thick, wavy brown hair, and as was the style in his day, he wore his cap to the read and side of his head. He also wore his collared jersey tacked up, close to his neck. He was immensely popular in Chicago, largely because of his steady leadership and outstanding play in the outfield. He had a strong arm, one year he threw out 20 baserunners, and he played shallow enough to peg a runner at second base on base hits several times. He typically hit second in the order, where he showed patience (about 70 walks per year) and was gifted at the sacrifice bunt.

In five years as player/manager of the White Sox, Jones won nearly 60 percent of the time, and he was well respected in the game despite a rascally temper that he often aimed at the umpires.

17. George Davis

By all accounts, it appears he was a brilliant shortstop, in some ways the Ozzie Smith of his time, which started as a professional in 1890. He actually only played parts of six seasons, the last stage of his career, with the White Stockings. He only batted .259 with six home runs for Chicago, but his defense at shortstop was so damn good, he rates this high on the all-time franchise list. In his prime, in 19th century “base ball,” Davis was a heck of a hitter too. One of eleven players on this list who has a plaque in Cooperstown.

16. Ray Schalk

He was only five-foot-seven, which was tiny even for his era. In fact, White Sox pitchers complained to manager Kid Gleason that the young Schalk was too scrawny to catch them. But eventually Schalk became the catcher of choice for Eddie Cicotte, who had about ten different pitches, including a knuckle ball and a knuckle curve.

The White Sox have had two Hall of Fame catchers and both were better known by their nicknames: Carlton Fisk was “Pudge” and Schalk was “Cracker” because a teammate (or maybe a coach) thought he was a “Cracker Jack player,” which in those days was a popular treat.

15. Luis Aparicio

Aparicio was a regular in all of his 18 seasons in the major leagues. I can’t find anyone else who did that, who came in as a rookie and started and was still a starter in his last season and every one in between. Despite being pretty small and putting himself in harm’s way around the bag at second, Little Looey was a durable fella.

14. Doc White

White’s father was a physician in Washington D.C., and it was expected that his youngest son Guy would follow in his footsteps. He didn’t: instead starring for the Georgetown baseball team and earning a contract with the Phillies after his senior season. But thanks to his dad and his eventual dentistry degree, Guy also earned the nickname “Doc.” His outstanding professional baseball career postponed his chance at straightening teeth.

White ended up on the White Sox in one of those contract squabbles that happened a lot back at the turn of the twentieth century, and his career quickly blossomed. He had three straight seasons with an ERA under 2.00, and in 1907 the skinny lefthander won 27 games for Chicago. He was the winning pitcher in the clinching game in the 1906 World Series victory over the Cubs.

In 1904, White pitched five consecutive shutouts, a record that stood for more than 60 years until Don Drysdale broke it in 1968. When Drysdale tied his mark, 89-year old White sent a congratulatory telegram, urging Drysdale to break his mark.

13. Robin Ventura

One of the best college baseball players of all-time, Ventura was named All-American three times at Oklahoma State University, where he attended the school at the same time that Barry Sanders was shaking and shimmying on the football field. Ventura had an NCAA-record 58-game hitting streak for the Cowboys. Years later he was inducted into the OSU Hall of Fame on the same day as Sanders and singer Garth Brooks.

12. Minnie Minoso

Minoso had more than 4,000 hits in professional baseball: roughly 1,900 in Major League Baseball, 1,100 in the Mexican League and minors; and 1,000 hits in the Cuban League and the negro leagues. He’s one of nine hitters to top 4,000 professional hits. The other eight are (in order of hits): Pete Rose, Ichiro Suzuki, Ty Cobb, Hank Aaron, Derek Jeter, Jigger Statz, Julio Franco, and Stan Musial.

The folks keeping Minoso out of the Baseball Hall of Fame are failing to appreciate the full measure of his career and the prejudices that prevented him from showing his talents in the top league in the United States.

11. Nellie Fox

Parents are your biggest fans. Fox’s mother wrote a letter to Connie Mack when her son was 16 asking for a tryout for young Nelson. A few weeks later he traveled the 60 miles by train from little St. Thomas Township to Frederick, Maryland, the site of the A’s spring camp. Fox wore a pair of borrowed cleats and the jersey of the St. Thomas team that he and his father both played for. At that point he was a runt, weighing no more than 145 pounds. He looked like he should have been the bat boy. But Mack liked the way Fox hustled and he was impressed at how the teenager made contact on almost every pitch he swung at. He signed Fox to a contract but Nellie’s career took a detour when he was drafted into the Army. Finally, in 1947 the little second baseman debuted for the A’s and he eventually played nearly 2,300 games in the majors at second base.

10. Mark Buehrle

There are three ways to get batters out in the major leagues:

- Throw hard

- Use a gimmick pitch

- Pitch in front of great fielders

A pitcher who has #1 is like gold: teams have sent scouts to dusty little towns where there are no train tracks, just to catch a glimpse of a kid who can bring the heat. The pitcher who uses a gimmick pitch is undervalued, baseball experts are suspicious of him, they have to be proven that there’s some way for the pitcher to get guys out. The practitioner of a knuckleball or an underhand “submarine” pitcher must fool batters again and again to earn a chance in The Show. Those pitchers who rely on #3 (great defense), usually don’t last long. They may defy the odds for a short time, but eventually big league hitters will punish them.

In the history of baseball there have been very few pitchers who violated this Rule of Three. If you chart the best pitchers in every era and look at what they did, you’ll find most of them are fastball pitchers: most of them exceed the league strikeout rate. If they don’t, they probably have an excellent pitch like a curve, screwball, forkball, or a spitball.

There’s a small group of pitchers who live outside these rules: lefthanders with great control who don’t fan a lot of hitters, but get a lot of ground balls, hence a lot of double plays. These pitchers surrender a lot of hits, but few home runs. The prototypical pitcher in this group was Tommy John, who pitched for 26 years.

So, you’re probably thinking Mark Buehrle must be that type of pitcher, a Tommy John type. He’s not. Buehrle was lefthanded, he had great control (walked two batters per nine innings), he struck out few batters compared to the league. Check, check, and check. But Buehrle was not a ground ball pitcher, he allowed about the average number of ground balls, in fact he was more of a flyball pitcher. Given the number of balls he allowed to be put in play and the fact that many were hit in the air, Buehrle shouldn’t have been as successful as he was. But he posted a career ERA+ of 117, meaning he allowed earned runs at a rate 17 percent below league average. He won more than 200 games, he pitched in a rotation for fifteen years, and had a winning record fourteen times.

Buehrle had a remarkably consistent career. Once he entered the White Sox rotation in 2001, he made at least 30 starts every season for fifteen straight years. Only four other pitchers have done that, all of them guys you’ve heard of: Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Warren Spahn, and Gaylord Perry. In 14 straight seasons he pitched at least 200 innings, joining the previously mentioned four plus Don Sutton, Phil Niekro, and Greg Maddux. Famous for not throwing between starts and shunning intense off-season workouts, Buehrle was extremely durable, and he was never on the disabled list.

It’s not immediately clear why Buehrle was able to skirt the rules and sustain a long, successful career. He was an average looking lefty with average looking stuff, who only ever got one vote for the Cy Young Award, gave up loads of hits, and worked a lot of innings with runners on base. Yet, Buehrle won a lot of games and pitched one of the few perfect games in baseball history. How did he do it?

Buehrle did not pitch better with runners were on base, and he did not have superior defensive teams behind him. But he had three things that worked heavily in his favor: (1) he was an excellent fielding pitcher, and (2) he held runners on the base, and finally (3) Buehrle pitched very quickly. It’s obvious why the first two points worked in his favor, but worth pointing out that per 32 starts, Buehrle allowed four stolen bases (he allowed only 59 stolen bases in his entire career). By comparison, Steve Carlton allowed 14 every 32 starts, and Fernando Valenzuela allowed 17. The third factor was beneficial because it kept batters in the box, disrupted their timing, and made them uncomfortable. Quite frankly, Buehrle did all the things that are hard to quantify and he did those things brilliantly. That’s why he is one of baseball history’s most remarkably unique pitchers.

9. Billy Pierce

Pierce was a unique pitcher: short and skinny, a purveyor of off-speed pitches and varying arm angles. He hid the ball well, which made his fastball seem faster than it was. He had a 12-to-6 curveball and a sidearm curve that fluttered in on lefties. He was brutal on lefthanded batters. Ted Williams batted .247 against Pierce, calling him the “toughest lefty I ever faced.” Three lefthanded-hitting batting champions — Billy Goodman, Pete Runnels, and Mickey Vernon — combined to hit .196 off Billy.

8. Eddie Cicotte

Eddie Cicotte was a tall righthander who could throw anything to the plate and get batters to swing and miss. He had a two-seam fastball, a four-seam fastball that sailed up (or rather did not drop as fast as would be expected), a screwball, and a slider. Cicotte loved to throw a knuckleball, and his curved. Like most top pitchers of his era, he also threw a spitball. But his favorite pitch was his knuckler, he was one of the first pitchers to master it.

Cicotte was just as good as Stan Coveleski and Herb Pennock and Waite Hoyt, others in his league who went on to be elected to the Hall of Fame. The reason you don’t hear much about Eddie today is that he was at the center of the ring that fixed the 1919 World Series. Gamblers paid the White Sox ace $10,000 in advance of the World Series. He was instructed to hit the leadoff man in Game One to indicate that the fix was on. He did, and the “Black Sox” lost the series thanks to his well-placed batting practice tosses to Cincinnati batters. Eddie also committed two errors. He lost twice, winning one game when he was worried that the gamblers were not going to pay his teammates.

7. Wilbur Wood

Wood was a New Englander, he grew up rooting for the Red Sox in the era of Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, and Johnny Pesky. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey took the word of one of his scouts in Massachusetts and authorized a $25,000 signing bonus for the pudgy kid with a good curveball. But Wood never did squat with his curveball or middling fastball. He didn’t become a 20-game winner or All-Star until he mastered the most difficult pitch in baseball.

A number of sources claim Hoyt Wilhelm taught Wilbur Wood the knuckleball when they were teammates on the White Sox. That’s not true, Wood threw a knuckler when he was with the other Sox in the early 1960s, it just wasn’t very good. Wilhelm helped Wood perfect the knuckleball, changed his arm angle, encouraged him to throw it 100 percent of the time. That’s exactly what Wilbur did, and of course he owed Wilhelm much of the credit for the success he enjoyed in the second-half of his career.

Wood might be the most underrated pitcher in baseball history. We have him ranked among the top 100 pitchers of all-time, but there are probably few people who would remember his name if they looked at that list. Why is he underrated? Because he threw a knuckler, and because he pitched on poor teams. Experts would rather slobber all over Don Sutton than admit that a round guy with a weird pitch was better. But Wood was better than Sutton.

For five years, his prime as a starter, Wood averaged 45 starts and 336 innings per season. He pitched about 20 percent better than league average. That’s tremendous value, and that’s why his Prime WAR (bext five straight seasons), WAR7 (best seven seasons), and WAR3 (best three) rate among the top 50 all-time. Before Chuck Tanner made him a super starter, Wilbur pitched five years as one of baseball’s most effective relief pitchers (2.55 ERA, 137 ERA+, and 109 IP in 65 games per).

6. Red Faber

Faber had a unique manner of throwing his signature pitch, the spitball, which helped him win 254 games and earn a place in the Hall of Fame.

Even though Faber was allowed to throw the spitter legally his entire career, he could not simply spit or lick his fingers and toss it to home plate. He needed to disguise his intention so as to fool the batter. Faber favored licorice or slippery elm, which he chewed in tablet form. The slippery elm made his saliva more useful on a baseball. Many pitchers concealed their substance of choice on their body or their uniform, but Faber had the slippery elm in his mouth, so he would wipe his glove-hand across his face and place some of it on his wrist. From there, he would typically adjust his sleeves to grab a dollop. When he wanted to apply it to the baseball he would move the ball across his non-pitching elbow and lather it up. He could make these movements look so natural that opposing teams were not sure if he was wetting the ball or not. Many batters simply assumed he would throw his spitter every pitch.

5. Big Ed Walsh

“If Ed Walsh was not the greatest pitcher who ever lived, he was certainly the most valuable in his prime. He could pitch as well as anyone. But he had tremendous added value because his great strength allowed him to pitch out of turn and save a whole raft of games for other pitchers.” — Johnny Evers

4. Eddie Collins

Collins had cartoonishly large ears, a prominent adam’s apple, sunken chin, and a long face. His smile curled up at the corners in a way that made him look unintentionally sinister. He had large lips and a bulbous nose, in fact it appeared as if everything on his head was big. That must have included what was in his head.

A college man, Collins was smart, intuitive, and some would say, scheming. Collins went directly from Columbia University to professional baseball, and he shot quickly to the big leagues, where he was so brash he earned the nickname “Cocky.” He was a baseball nut, loved the game. He was also a tremendous competitor who led six teams to the World Series.

As a player, Collins was very fast and athletic with boundless energy. Everywhere Eddie went on a baseball field, he ran. He choked up on the bat and hit the ball to the opposite field more than he pulled it. He was overshadowed as an offensive force because he arrived in the league almost precisely when Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker did. Cobb was born in December of 1886, Collins was born five months later, and Speaker was born the following April. They played in the American League together for 22 years, the last season as teammates.

3. Frank Thomas

In his first eight seasons, Big Frank went 330/452/600 and won two MVPs. He probably should have won the award when he was 23 in 1991, and in 1997 when he had his best season. Thomas won the MVP in his fourth and fifth best seasons, but not in any of his three greatest seasons. It’s unlikely that has happened to any other player. Maybe Ted Williams?

2. Ted Lyons

Lyons was known for pitching once per week late in his career. That’s why they called him “Sunday Teddy.” He basically worked that way exclusively after the age of 33, extending his career to the age of 45. Lyons made by far the most “well-rested” starts in history:

Most Games Started with Six Days or More Rest, Career

Ted Lyons … 175

Red Ruffing … 123

Freddie Fitzsimmons … 116

Eddie Lopat … 105

Curt Simmons … 105

Nolan Ryan … 99

Tom Zachary … 97

Lefty Grove … 94

Tommy Bridges … 93

Sad Sam Jones … 93

Seven of these ten pitchers were active in the 1920s and 1930s, Lopat pitched in the 1940s and 1950s, and so did Simmons. Ryan is the only modern pitcher on the list, but he was never a “weekly pitcher”, he makes the list because (a) his career was so long and the number of starts over 5 days accumulated through natural reasons (breaks, days off in the schedule) and (b) he was held back due to injury several times each year from about age 35 on.

It worked: Lyons had a higher winning percentage, lower ERA, and better strikeout-to-walk-rate, relative to the league as a weekly pitcher as opposed to pitching in a four-man rotation. He was not being babied: in his last four seasons Lyons started 69 games in the weekly format and completed 61 of them. In 1942 the 41-year old started 20 games and completed them all, including two that went into extras. He averaged more than nine innings per start that year.

1. Luke Appling

A few of the best “old” shortstops in history were Bad Bill Dahlen, Ozzie Smith, and Omar Vizquel. But the best was Luke Appling. “Ol Aches and Pains” was playing a very good shortstop when he was 36 years old, in fact that was his second-best season. His fifth-best season came when he was 39.

Appling won his second batting crown when he was 36 years old, and he ultimately hit .300 fifteen times. He played 22 years in the big leagues, every game as a member of the White Sox. Late in his career the franchise held a Luke Appling Day, and owner Charles Comiskey Jr. presented his popular shortstop with a check for $100 for every season he’d played in a Chicago uniform. “On behalf of my father, my family, the organization, and my mother, we thank you for your great service to the city and the club,” an attached letter said.