Welcome to our series on the 20 greatest players for each franchise. This time we look at the Detroit Tigers, charter members of the American League.

Baseball’s second deadball era was in the 1960s. From 1961 to 1972, the American League saw offense plummet by 22 percent from established levels. They lost one run scored per game. It might be difficult to understand how much the drop in offense impacted the game, but it was tremendous. Dick McAuliffe had the meat of his career during that span, and as a result, all these years later the stats on the back of his baseball cards look unimpressive because of it.

Why was there a second deadball era? The evolution of pitching accelerated at a rate that outpaced offensive production. New training methods and stronger, more athletic pitchers were putting the defense in control, and hurlers stood atop baseball on a mound that was taller by five inches than it is now. “Great” pitchers fell from the rafters.

From 1966 to 1969, his peak four-year stretch, McAuliffe had 20 WAR. He was arguably the best middle infielder in baseball. In his best four-year stretch, Jeff Kent had 23 WAR. But when Kent did it, he put up 100 RBIs and 30+ homers a year and so on. McAuliffe hit 23 and 22 and 18 homers here and there. He put up a slugging percentage one season of .458, but that figure was more impressive than Kent’s .565 in 2002 when he was sixth in MVP voting.

Lowering the mound didn’t bring the runs back, it took a radical new rule change called the designated hitter and artificial turf to do that. It also helped that the strike zone gradually got smaller. By 1977 the AL was coming back to the run levels it had seen in the late 1950s. Had McAuliffe played from 1975 to 1990 instead of 1960 to 1975, he would have scored more runs, driven in more runs, and hit more home runs. He would have drawn more attention than what he got, which was mostly due to his odd batting stance.

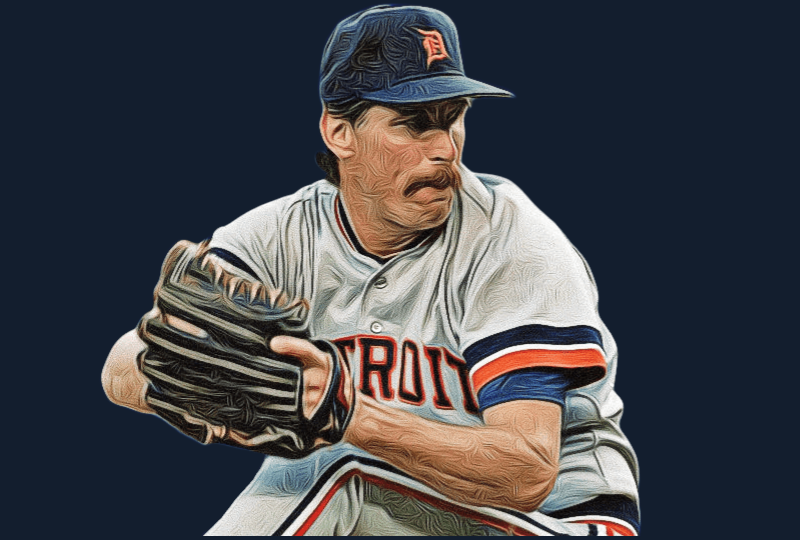

Baseball is an imitation game. Really, all sports are. Once teams prove they can achieve success shooting threes or utilizing an option offense, other teams will copy it. In the early 1980s, a new pitch was the rage in baseball, a pitch that Bruce Sutter was using with phenomenal success out of the bullpen. They called it the forkball because the index and middle fingers surrounded the baseball on either side, like the tines of a fork. That pitch, which is completely responsible for Sutter being in the Hall of Fame, also helped Morris get to the same place.

Before he learned the forkball (sometimes also called a split-finger) from teammate Milt Wilcox in 1982, Morris relied on a fastball, slider, and a pretty bad changeup. With the forkball, Morris had a pitch that complemented his fastball and made him difficult to hit against because he was able to use the same arm slot for the pitch as he did his breaking ball.

“A forkball actually comes out of your hand with the rotation of a curveball,” Morris explained. “Because of the pressure on your fingers, there’s no way you’re going to have the same velocity you do with your fastball, therefore it’s kind of like an offspeed curveball. Once I learned how to keep it down, and literally bounce it at times, a hitter couldn’t sit on both. He couldn’t sit on a fastball and a forkball. It’s a devastating pitch.”

Less than two years after learning the forkball, Morris had the pitch going very well in his second start of the 1984 season in Chicago. It was a Saturday afternoon and the game between the Tigers and White Sox was on national television. Morris had his forkball dropping so much that day that he walked six batters, even walking the bases loaded early in the game. The pitch was bouncing in front of catcher Lance Parrish, but Morris had such movement on it that he escaped trouble. He carried a no-hitter into the seventh, eighth, and finally the ninth inning. The White Sox barely got the ball past the mound, bounced grounders to first or back to Morris. He struck out a few guys and got his no-hitter, the first by a Detroit pitcher in more than two decades. Morris later estimated that he threw 40 percent forkballs.

“I’m not sure Ruth could have hit the split-finger,” Morris said. “I’ve seen pictures of Ty Cobb swing, and I know he couldn’t.”

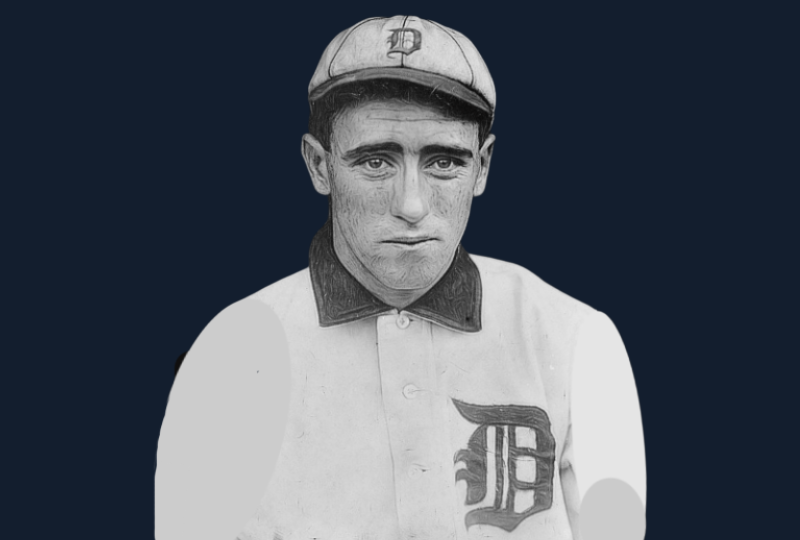

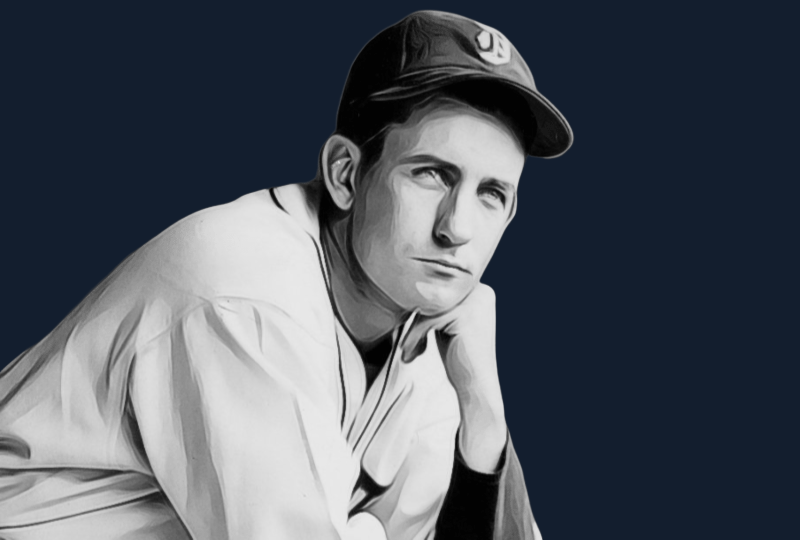

Bush was the best player found and signed directly by Frank Navin, who held controlling interest in the Detroit Tigers for more than 20 years. A tiny fella from Indianapolis, Bush defied the odds and outplayed players with better pedigrees as he moved his way through the professional ranks, ultimately landing a chance with the Tigers in September of 1908. Bush joined a team embroiled in a tight pennant race, and he proved important, running the bases like he was Ty Cobb’s little brother. Detroit won the pennant but regular shortstop Charley O’Leary returned from injury and got to play in the World Series. Bush took that personally and vowed to never be beaten out of a job again. The following year he began a 13-year stranglehold on his job in the burgeoning Motor City.

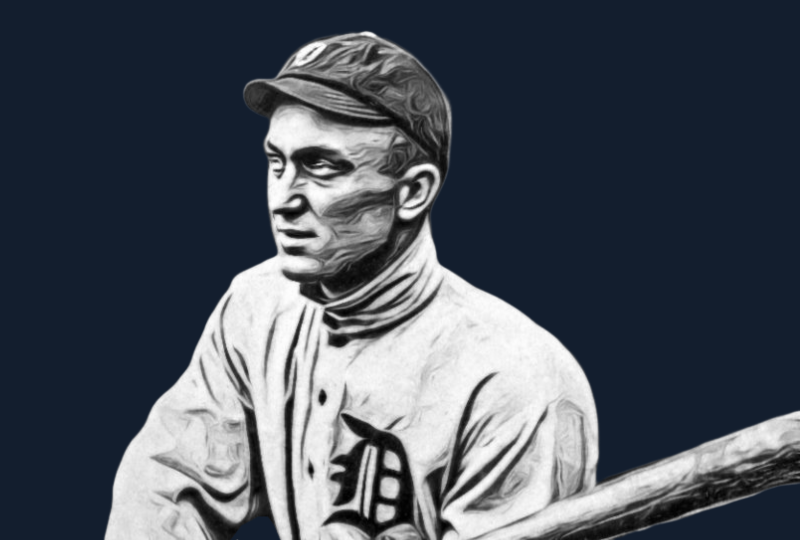

When the greatest offensive lineups are discussed, the Detroit Tigers of the Deadball Era are often short-shrifted. They had one of the greatest offensive weapons in baseball history in the middle of their lineup, Ty Cobb. Every season he would do his Ty Cobb things, like steal 85 bases, get 225 hits, and lead the league in runs and runs batted in while hitting close to .385 or .390. Then there was Sam Crawford, the moody right fielder who was one of the best sluggers of the first 25 years of the twentieth century and smacked more than 300 triples. Detroit had a left fielder named Bobby Veach, who hardly anyone remembers, but who was very good. If you want a comp for Veach at the plate, he was a lot like Fred Lynn or David Justice: a strong left-handed hitter who could hit a homer, drive the ball, and produce runs. Cobb, Crawford, and Veach rate as one of the greatest outfields ever, even if they weren’t chummy.

At the top of the order, getting on base in front of the three big Detroit boppers, was little Donie Bush, all 140 pounds of him. At 5’4, Bush crouched down so his strike zone was small, and he had a keen eye, leading the league in walks five times and averaging 99 walks per 154 games. He scored an average of 111 runs per. He was an ideal leadoff man.

That Detroit lineup, formed on the quartet of the three hard-hitting outfielders and Bush, stacks up well with the Big Red Machine of the 1970s for run-scoring. Later in the 1910s they added Harry Heilmann, a four-time batting champ. Here’s how the Tigers ranked in runs scored in the American League during the Bush/Cobb et al period:

1909 (1st), 1910 (1st), 1911 (2nd), 1912 (3rd), 1913 (3rd), 1914 (2nd), 1915 (1st), 1916 (1st), 1917 (2nd), 1918 (4th), 1919 (3rd).

In 1915 the Tigers were 163 runs better than the league average, or more than one full run higher than any other team. That season Bush had a down year, hit only .228, but walked 118 times and stole 35 bases, still managing to score 99 runs. The three outfielders averaged 35 doubles, 14 triples, and 108 RBI. Detroit had a +181 run differential and won 100 games, but finished second to the Red Sox, who had an actual pitching staff.

Bush has great defensive stats, still holds the record for assists by a shortstop in a single season, but that’s largely because the Tigers had a lot of ground ball pitchers and their infield grass was high enough to hide a small child. His double play stats (as noted by Bill James) are poor, and Bush made a lot of errors, and a large number were throwing errors, as compared to others at his position. I think his arm was a little weak, and his throws would hit the dirt short of first base too often.

Bush’s playing career could have continued as a third baseman but he accepted the revolving door position as manager of the Senators. He didn’t fare well, but Bush was an obedient old ballplayer who was respected by the dusty old men who guarded the gates of the game. He landed in Pittsburgh where he won a pennant with a talented team, really as nothing more than a push-button manager. He nearly messed up that team, proved his mediocrity in subsequent seasons, and was fired after alienating his players. The White Sox and the Reds gave him a chance in the dugout, but Bush was a crusty manager, one of those “back in my days we played the game right” types. His players never liked him much and he managed his last big league game in 1933. He later managed teenager Ted Williams in the minor leagues, helping the tall, thin hitter with his approach at the plate.

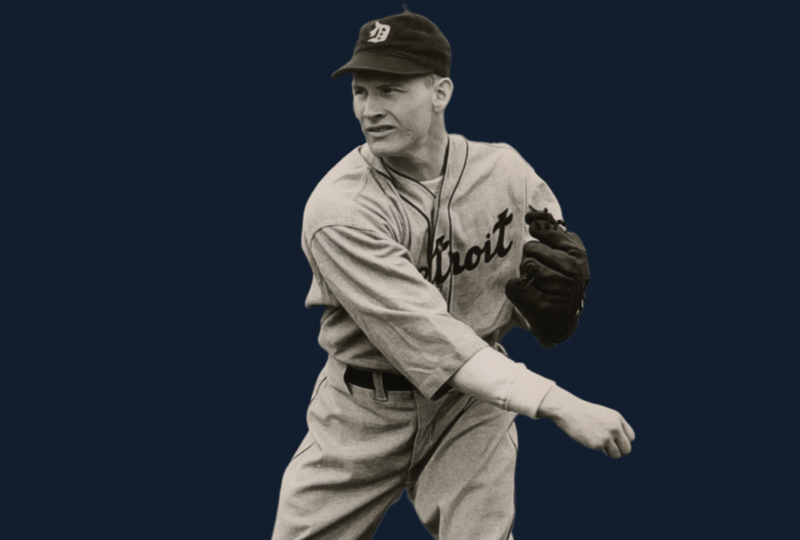

Trout was nearly deaf in one ear and had bad ringing in his other ear, which is why he had to stay home during World War II. During those tumultuous years, the thick-chested, hard-throwing righty was one of the best pitchers in baseball. He won 20 games in 1943, and 27 in 1944. Then in 1945, with the Tigers in a fight for the pennant, Trout won five games in September, including two by shutout, and also pitched out of the bullpen on one and two days rest down the stretch. He defeated the Cubs in Game Four of the World Series and two days later got 14 outs as a reliever while allowing only one run.

He was a fine hitter: his 20 home runs are 11th all-time among pitchers. And once, in a game in 1949, he relieved Hal Newhouser and pitched three-plus innings out of the bullpen in a tie game. In the ninth, he hit a grand slam to win the game for the Tigers.

Trout teamed with Newhouser and Virgil Trucks to form the famed “TNT” pitching duo for Detroit in the 1940s and early 1950s.

The Detroit Tigers gave Freehan a $100,000 bonus off the campus of the University of Michigan. That was probably the best money the team ever spent. The scout who gathered Freehan in for the Tigers was a man named Louie D’Annunzio, a baseball lifer who found pitchers Hal Newhouser and Billy Pierce for the franchise. D’Annunzio took note of Freehan when he was only 15 years old, and he did what a good scout does: he befriended the family. D’Annunzio was “the first guy in” and he knew all of the Freehan’s by name. He went to U of M to watch Bill play for the Wolverines, and he shook his hand at every important juncture of his amateur career. Later, D’Annunzio did the same thing with Ted Simmons, who ranks just ahead of Freehan on this list, and also grew up in Michigan. Simmons also attended U of M, but when he came out of college the rules had changed, and he was selected in the draft by the Cardinals with the tenth pick, five spots before the Tigers could get their hands on him.

Freehan was the premier catcher in the American League for a decade, and he’s the only receiver with that distinction not in the Hall of Fame. The timeline of the “best of the decade” catchers in the American League goes: Wally Schang, Ray Schalk, Rick Ferrell, Mickey Cochrane, Bill Dickey, Yogi Berra, FREEHAN, Carlton Fisk, Pudge Rodriguez, Joe Mauer. He ranks ahead of three of those catchers, but there’s virtually no chance Freehan gets a plaque in Cooperstown. Crouching behind the dish, he didn’t stand out.

Freehan and Mickey Lolich started the same game 324 times, a record for catcher/pitcher teammates (which used to be called a battery). Appropriately it’s Mickey in Freehan’s arms in one of the most iconic World Series photos of all-time, snapped seconds after Lolich finished his third win in the 1968 Series.

The forgotten third member of the famed Detroit outfield, which included Ty Cobb and Sam Crawford, and later Harry Heilmann. Veach was the cleanup man on those Detroit teams that scored a lot of runs, and with Ty and Wahoo Sam on base a lot, Bobby drove in a lot of runs: he averaged 104 RBIs per season.

In 1921, Veach, Cobb, and Heilmann had the most impressive offensive season ever by an outfield trio. They combined for a .372 average, drove in 368 runs, had 641 hits, 123 doubles, 43 triples, 47 home runs, and scored 348 times. The team hit a record .316, but they managed to win only 71 games.

In the years that Cobb was player-manager, Veach suffered under the thumb of his longtime teammate. The intense Cobb disliked Veach’s friendly relations with opposing players and he tried several times to trade Veach, eventually shipping his left fielder to the Red Sox prior to spring training in 1924.

When he was a very little boy, a motorcycle fell on Mickey’s left arm. He had it in a cast for a while and when it came off he favored it and became a lefthander. His hero when he was growing up in Oregon was Whitey Ford. After he opened a lot of eyes with his performance as a young pitcher in high school, several teams wanted to sign Lolich, including the Yankees. This was 1959. Ironically, Lolich snubbed the Yanks because they still had Ford and the young pitcher thought he’d have to wait in line to make it to the big leagues.

Four years later, in his fourth major league start, and his first in Detroit, Lolich faced Ford and lost. But he made the correct decision. Lolich was comfortable in Detroit, where he could learn his craft away from the glare of a large media market, and he didn’t have to be the #1 guy in the rotation for several years. That happened in 1971 after the Tigers traded the more controversial (and less talented) Denny McLain. Mickey won 25 games in 1971 and pitched an incredible 376 innings. It’s a wonder his arm didn’t fall off, but Mickey had a special post-game routine: he put his left arm under hot scalding water in the shower and made it numb. He insisted that he never had a sore arm.

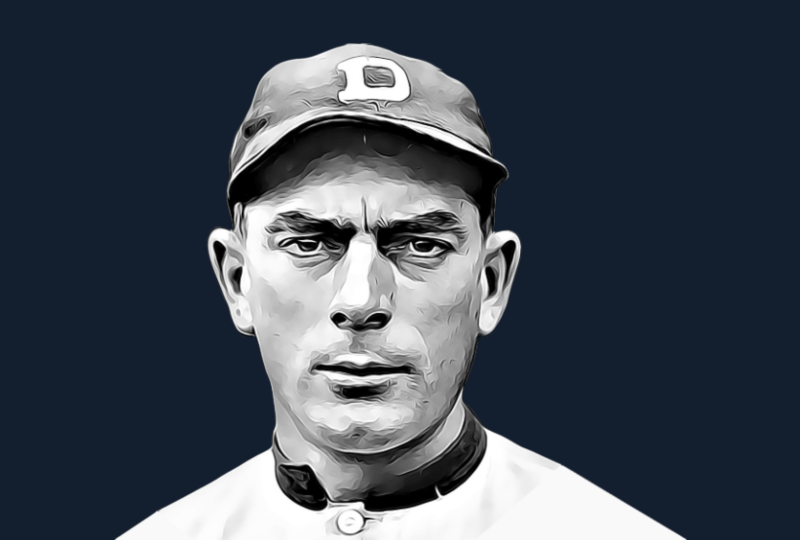

The most important inning in the history of the Detroit Tigers was probably the ninth inning of Game Six of the 1935 World Series. The Tigers and Cubs were tied, Detroit needing one run to capture their first title. Tommy Bridges, the little Detroit ace, was on the mound. Stan Hack led off for the Cubs and lofted a deep fly into left-center that went to the wall. He slid into third with a triple. Only 90 feet separated Hack from giving the Cubs a lead and a shot at a Game Seven. But the Cubs had to go through Bridges to do it, and Bridges was tough as hell.

The best pitch in Bridges’ arsenal was his curveball. Babe Ruth deemed it the best breaking ball he ever faced. It was an old fashioned “12-to-6” curve, breaking straight down on the plate. Just when the batter thought he was getting a bead on the pitch, it would dive like a U-boat. At this crucial juncture of the game, on the biggest stage in sports, Bridges went to his strength. He tossed three curveballs to Billy Jurges, striking him out on three pitches. The next Cubs hitter also got a dose of “Uncle Charlie” and was sent back to the bench after missing three pitches. Finally, Bridges retired Augie Galan on a curve for a strike, a curve low, a curve that Galan swung at and missed, and a curveball that Galan lofted lazily to left field for the third out. Bridges had thrown ten straight curveballs to get out of the jam, preserving the tie. The Tigers scored in the bottom of the ninth and won their first world championship. After the game, Mickey Cochrane glowed: “I can say it only one way: he’s 150 pounds of sheer guts.”

The Florida Marlins signed Miguel Cabrera to his first professional contract only ten weeks after his 16th birthday, giving the Venezuelan a $1.8 million signing bonus. They beat out the Blue Jays, Dodgers, and Red Sox, all of whom offered Cabrera more money. But the Marlins had a trump card: their shortstop was Álex González, who was also from Venezuela, and happened to be Cabrera’s favorite player.

16-year old Miggy was a chunky, happy kid, but a man-child on the baseball field. “He is one of the most-touted prospects out of that country in years,” Marlins general manager Dave Dombrowski said at the time. Originally, Cabrera was a shortstop, and agile enough with a very strong arm, but the Marlins figured he would slot in at third when he was ready, next to González.

“He’s got the power to [play third base],” Marlins scouting director Al Avila said. “He’s a big-limbed kid but very graceful. That’s what makes him so good.” Dombrowski added, “He has impressive bat speed, and if he fills out physically, he could have impressive opposite field power in the big leagues. He can drive the ball out of the park.”

Well, Al and Dave were right on that one. Less than four years later, minus the baby fat and with muscle on his frame, Cabrera made his big league debut. In that game he batted eighth in the lineup, one spot behind his hero González. In the 11th inning, Miggy hit a towering game-winning, walkoff homer to center field. He hit 12 homers in half a season as a rookie, and that fall in the World Series, the first time he faced Roger Clemens, Cabrera crushed a fastball for a two-run homer in Game Four. The ball was hit to the opposite field.

Cabrera became a superstar because he could hit the ball with authority the other way, and up the middle too. Defenses couldn’t stack one side of the field against him. He hit 33 homers in his first full season, and did it again the next season when he batted .323 with 198 hits. He received MVP votes every year as a Marlin, but the franchise doesn’t like sustained success, so they traded Cabrera after the 2007 season when Dombrowski came back to get him. As GM of the Tigers, Dombrowski coveted Cabrera, getting him to Detroit in a blockbuster eight-player trade that will go down as one of the biggest heists in baseball history.

In his first four seasons as a Tiger, Cabrera won every leg of the triple crown: the home run title in 2008, the RBI title in 2010, and the batting crown in 2011. The following year he won all of them in one season, the first triple crown in 45 years. He won the batting title for the third straight year in 2013, and his second consecutive MVP award. In each of his first 14 seasons, Cabrera received MVP votes.

Cash admitted he used a corked bat in 1961, but physicists will tell you the cork doesn’t help a ball go farther, it only helps a batter swing faster. A corked bat has less mass, and according to tests performed for the Mythbusters television show, a corked bat will exert half as much force on a baseball than a regulation bat. Corking a bat doesn’t help, it hinders efforts to hit a baseball harder and farther. Of course, there may be a placebo effect. Many, many hitters have been caught using a corked bat, and no one else, to my knowledge has ever had a freak season using a corked bat. One of Pete Rose’s bats was found to be corked, a bat he used for two seasons, hitting a grand total of two home runs. Sammy Sosa used corked bats, and so did Albert Belle, but they were helped by syringes, not cork.

The most likely reason for Cash’s phenomenal season in 1961 was expansion and subsequent weaker pitching in the league. Cash hit .390 with a .724 slugging percentage against teams in the bottom half of the league that season. The same year, Roger Maris hit 61 homers and his teammate Mickey Mantle hit 54.

“He was one of the truly great hitters, and when I first saw him at bat, he made my eyes pop out.” — Joe DiMaggio

Verlander and Warren Spahn are the only pitchers to finish second in Cy Young Award voting three times. Spahn won the Cy Young once, Verlander has won it twice (through 2020), and also has an MVP award. Now that it comes up: Verlander is the most decorated pitcher in history. He’s the only pitcher to win a league MVP, Cy Young, Rookie of the Year, and MVP of the League Championship Series. He’s won Player of the Month, Pitcher of the Month, and a pitching Triple Crown. The only award he’s missing is MVP of the World Series.

Baseball history is sprinkled with stories of pitchers turning their careers around after mastering a new pitch. The pitch that turned Newhouser into a star was called the “nickel curve” but we would call it the slider today.

Newhouser learned the slider in 1944 from Paul Richards, a veteran catcher who quit his job as a minor league manager to play during the war years. Newhouser had long fingers, and when he threw the nickel curve it came out of his hand much like his fastball. Batters didn’t realize it wasn’t a fastball until it sank at the last second. Overnight, Hal was nearly unhittable.

In 1944 Prince Hal won 29 games and the American League Most Valuable Player Award, following it up with a second MVP award in 1945 and a second place finish in 1946. Newhouser won 80 games from 1944 to 1946, and at one point he won 40 of 48 decisions. He was 15-4 in September over those three years and his performance down the stretch in 1945 secured the pennant for Detroit.

After the talent returned from the war, Newhouser was still a great pitcher, and had several good seasons. A sore arm slowed him down and he only made 38 starts after the age of 30, but it was hard to overlook what he’d done over his seven-year peak from 1944 to 1950 when he averaged 22 wins and more than 280 innings.

It’s been said of Sam Crawford and Ty Cobb that they had the worst relationship of any long-term superstar teammates. I’m not sure about that. Jeff Kent hated the guts, the bones, the marrow of Barry Bonds, and Bonds disregarded Kent like he did everyone. I will say this: Jeff Kent will never campaign for Barry Bonds to make the Hall of Fame, or vice versa. But Ty Cobb made sure Wahoo Sam got into the club. He wrote letters and gave interviews pushing for his old teammate to be elected, which Crawford was in 1957. Crawford reportedly wrote a letter to Cobb thanking him for his support and when they saw each other on the porch of the Otesaga Hotel in Cooperstown for induction weekend, Wahoo Sam embraced his old teammate.

After the passage of the 18th amendment in 1919, it was illegal to consume alcohol in the United States. Rather quickly it became possible to get liquor from illegal establishments, most of them secretive and invite-only, known as “speakeasies.” It’s estimated that during Prohibition, there were as many as 100,000 speakeasies in the U.S. In Detroit, the most popular gathering spots to wet your beak were the speakeasies in Corktown near the ballpark or in the basement of a famous hotel downtown. During the 1920s when illegal alcohol was flowing heavily and a poker game and dancing girls could be found in these password-protected dives, Heilmann was one of the frequent guests. He was famous for being one of the big spenders. When the Yankees visited Detroit, Babe Ruth sought out Heilmann to find the best parties with the prettiest girls.

Most Important Seasons by a Shortstop:

The Tigers hired Eddie Brinkman to work with Lou Whitaker and Alan Trammell when they first teamed together in Double-A ball. “It was Tram’s ability to play shortstop that made me better,” Whitaker said. “I could expect a good throw, I knew he’d be there, he was a natural athlete, he was smooth.”

Early in his career, Whitaker was one of the fastest players in the league, but he ran funny. As a kid his legs were severely bow-legged, and doctors told his family to put him in braces, but they couldn’t afford it. So, Lou’s uncles would twist and turn his legs every day until they straightened. Still, Whitaker carried that with him onto the diamond: he had a tip-toe gate to his stride that made it seem like he wasn’t running as fast as he was.

Among the second basemen, Rogers Hornsby or Rod Carew were the best pure hitters, Joe Morgan was the most complete offensive package, Jackie Robinson was the most thrilling, and Gehringer was probably the most complete player. “The Mechanical Man” hit for average, ran the bases well, was a very good fielder (better than Hornsby and Morgan), and had a stronger arm than any man rated ahead of him on our list. The only flaw in Charlie’s game was that he didn’t hit the long ball, but he averaged 40 doubles, 10 triples, and 13 homers per season.

“Many players intentionally make every play look as difficult as possible,” wrote H.G. Salsinger. “Gehringer managed to make them all look easy.”

Al Kaline was the last of a breed of men who dedicated their entire adult lives to one team. He was 18 years old when he signed his first contract with the Detroit Tigers at the kitchen table in his parent’s home. He was wearing his prom suit. Starting that evening in 1953, with the exception of about eight months, Kaline was in constant employment of the Detroit Professional Baseball Club. He spent 22 seasons as their All-Star outfielder, followed by 27 years as a broadcaster, before he was hired as a special assistant to the general manager, a position he still held when he died in 2020. Over the years, Kaline mentored young players from Kirk Gibson to Travis Fryman to Curtis Granderson. At every point in Tigers’ history since the first year of the Eisenhower administration, Kaline was there.

When the Tigers found it necessary to fire a good baseball man named Les Moss only two months into his first season as their manager because Sparky Anderson was available, Kaline sat in on the conversation to cushion the blow. When owner Tom Monaghan hired Bo Schembechler, a former college football coach, to modernize the team’s spring training facilities, it was Kaline who explained the plan to the players. When Lou Whitaker said some things that were insensitive during the 1994 labor stoppage, Kaline huddled with Sweet Lou to suggest an apology. When Miguel Cabrera had embarrassing off-field incidents with alcohol, Kaline was one of the first men in the organization who counseled him. And so on.

The Orioles had that sort of relationship with Brooks Robinson, the Twins with Harmon Killebrew, the Dodgers with Tommy Lasorda. But it’s increasingly rare, if not obsolete. Today, most superstars don’t want (or need) a job after their playing career. Kaline truly was “Mr. Tiger.”

In 1942, The Sporting News polled 102 former managers and players, asking them to choose the greatest player of all-time. The second place finisher was Honus Wagner with 17 votes. The mighty Babe Ruth got 11.

The runaway winner was Ty Cobb, who got 60 votes, compared to 42 for the rest of the field. Many of the voters submitted comments, and here are a few of them:

“The greatest ballplayer to ever set foot on a diamond.”

“He had brains in his feet.”

“A fierce competitor and a team player.”

One voter, an unidentified former player who battled Cobb for years, said “Everyone in the league feared him, but we respected him.”

No one mentioned dirty play, nor did they say anything about Ty sharpening his spikes. That’s because Ty Cobb wasn’t a dirty player.

Let me rephrase that: Ty Cobb wasn’t the only dirty player.

Cobb once said, “When I began playing the game, baseball was about as gentlemanly as a kick in the crotch.” That about says it all.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.

No posts found!