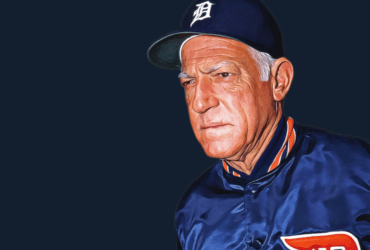

Baseball has lost one of its most successful managers and most marvelous characters. The passing of Sparky Anderson today at his home in Thousand Oaks, California, comes all too soon for a man who looked like a little old man for more than 40 years. Anderson, the Hall of Fame manager known for guiding two of the greatest teams of his generation and his magnetic appeal with the media, was just 76 years old.

Sparky Who?

When the Cincinnati Reds named 36-year old George Anderson as their manager during the 1969-1970 off-season, newspapers in the city asked “Sparky Who?” Within a few short months, Sparky was a household name in Cincinnati and throughout Ohio, and soon he was one of the few men in sports who was known by one name.

In his first season in Cincinnati, Sparky’s Reds won 70 of their first 100 games (tying a record) on their way to capturing the pennant. Two years later, the Reds were back in the World Series, dubbed “The Big Red Machine.” In Cincinnati, Sparky guided a star-studded team that featured future Hall of Famers Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, and Tony Perez, as well as all-time hit leader Pete Rose and All-Stars Davey Concepcion, Ken Griffey Sr., and George Foster. In Anderson’s first seven seasons, the Reds won five division titles and four pennants.

Dubbed “Captain Hook” by the Cincinnati media, Anderson was one of the first managers to use his bullpen in ways that today we take for granted (or deplore). When he didn’t have starting pitchers who could go deep into the game, Sparky often switched relievers in and out to get the platoon advantage he needed in the late innings. He may have developed more top-notch relief pitchers than any other manager in history. Clay Carroll, Rawley Eastwick, Pedro Borbon, Tom Hume, Doug Bair, Aurelio Lopez, Kevin Saucier, Willie Hernandez and Mike Henneman all became bullpen stoppers under Sparky’s reign.

The Big Red Machine, Champions of Baseball

The 1975-1976 Reds are considered by many experts to be the greatest team of the post-expansion era. The ’75 club won 108 games and defeated the Boston Red Sox in one of the most exciting World Series ever played. The following season, the Reds gobbled up 102 more victories in the regular season and then proceeded to go undefeated in the post-season – the only team ever to do so in the playoff era. After two second-place finishes however, the Reds dismissed Sparky in a move that deeply stung the white-haired manager.

Hired by the Detroit Tigers

Several teams showed interest in Anderson, but he signed a multi-year deal with the Detroit Tigers and assumed the helm early in the 1979 season. With a young, untested group of players, Anderson quickly established himself as the authoritarian in Detroit. Famously, just weeks after donning the Detroit uniform, Sparky called out several players for lackluster effort. “It’s my way or the highway,” Sparky barked to the press. Within a few years, All-Stars Ron LeFlore, Jason Thompson and Steve Kemp were gone, along with others. Sparky announced he had the core of a winning team in place and promised a title in five years (coincidentally the length of his contract).

In 1984 the Tigers made Sparky’s prediction come true, rolling to 35 wins in their first 40 games as they enjoyed one of the finest seasons of any team in baseball history. The club set a franchise record with 104 victories and dispatched the Kansas City Royals and San Diego Padres easily in the post-season. With the triumph, Sparky became the first manager to win a World Series title in both the National and American leagues. The title served as vindication for Anderson after having been unceremoniously dumped by Cincinnati.

As much as Sparky had been identified with the Reds in the 1970s, he spent nearly twice as long in Detroit – 17 years. With the Tigers, Sparky guided the club to two first-place finishes and four second-place finishes. In his 26 years in the big leagues, Anderson finished in first or second place 14 times while suffering just six losing seasons. According to him, the team he was most proud of was the 1987 Tigers, who came from 6th place early in the season to win 98 games and the division title. “This bunch ain’t gonna be pronounced dead until the coroner does it,” Sparky said, “I’m telling you, I know this group, and they ain’t done yet.”

Took a stand against replacement players

Deep within Anderson were guiding principles that he’d inherited from his parents. When Major League Baseball braced itself for the possibility that replacement players would take the field for the start of the 1995 season, Anderson balked – refusing to manage them even in Spring Training. Tiger management tried to pressure Sparky into uniform, but the veteran skipper refused to take part in what he saw as a mockery. He was the only manager in baseball to take a stand. The incident helped pave his way out of Detroit, and Sparky retired following the ’95 campaign.

One of just eight managers to win at least three World Series titles, he was the first manager to win 100 games in both leagues. Though some called Anderson a push-button manager, he was named Manager of the Year four times and his career win total ranked third all-time when he retired. Anderson is the only skipper to be the all-time victory leader for two franchises, and he proved he was no slouch — in the World Series he defeated Dick Williams and Billy Martin, two of the best managers of the era. And even though he usually had teams that dominated their way to first-place finishes, he was able to coax his teams when they were behind. In baseball history just ten teams have overcome at least an 11-game deficit to finish in first place. Sparky is the only manager to guide two of those teams (1973 Reds and 1987 Tigers).

His enthusiasm for the game and his penchant for satisfying story-hungry reporters reminded many of Casey Stengel. Anderson was a master of hyperbole. Holding court in his office while sucking on his pipe, Sparky could go on for hours, often meandering off subject or belaboring a point repeatedly. He was famous for hyping young players he was fond of. Kirk Gibson was “the next Mickey Mantle.” Chris Pittaro, a young infield prospect in the mid-1980s, “would be in the middle of the lineup for Detroit for the next decade.” Of promising rookie pitcher Dave Rucker, Sparky said, “If you don’t like him, you don’t like ice cream.” During the 1976 World Series, Anderson peeved some Yankee fans when he stated that it would be “an insult to compare [Yankee catcher Thurman] Munson to Cincinnati catcher Johnny Bench.”

An astute observer of human nature, Anderson was a genius at handling different players. With the Reds he made no secret of the fact that he gave special treatment to his quartet of superstars: Bench, Morgan, Perez, and Rose. He was also especially fond of and effective with role players. Darrel Chaney, Champ Summers, Johnny Grubb, and Dave Bergman were three players whose careers especially benefited from playing under Sparky as role players.

In his Hall of Fame induction speech in 2000, Sparky was overly modest. “I got good players, stayed out of their way, let them play the game, and hung around for 26 years,” he said. But he was much better than that and anyone who ever played for him or competed against his teams knew it.