No one scans the backs of baseball cards anymore. They stare at a player’s Baseball Reference page. If one happens to browse their way to the B-R page of Earl Webb, they’re in for a shock.

67.

Yes, 67 doubles. Webb hit 67 doubles in one season.

That can’t be right, can it?

But it is. Earl Webb’s 67 doubles is a major league record, one that’s stood since 1931, more than four score ago, as Honest Abe might say. It’s a record that’s withstood the test of time and seems unassailable. But this season, Mr. Webb has a serious challenger. With a week left in the season, that unbelievable 67 is in danger of being bumped off the top of the list.

How does someone hit 67 doubles? Today, if a player hits 30 doubles, it’s a good season. A 40-double season puts a hitter in contention for the league lead most years. And 50, well 50 is rare.

Entering 2019, there had only been 100 50-double seasons in MLB history. Most of them were in the low-50 range. In 2018, Alex Bregman hit 51 for the Astros. Entering this season, only 21 players have reached 55 doubles. This year, three batters are at the 50-mark: a pair of Boston teammates (Xander Bogarts and Rafael Devers), and Nick Castellanos.

Castellanos has resurrected the ghost of Earl Webb, as he charges toward 60 doubles. On September 21, he hit his 58th. The Cubs’ outfielder has seven games left to dethrone Earl.

Who the hell is Earl Webb and how did he set a record that seems impossible? And was a man who hit 67 doubles in a season — a man with a career .300 batting average — out of the majors two years after setting the record?

When he was only 12 years old, Earl was lowered into the ground to work as a coal miner in Tennessee. It was a much different time, before child labor laws, before the minimum wage, before we realized how bat-shit crazy it is to lower anyone deep into Mother Earth to extract dead plant matter.

“At 14 years of age,” Webb said, “I began to drive a blind mule in the mines that had not been up in the daylight for 12 years. I was paid eight cents an hour for that.”

Ok, that sounds terrifying. For the boy and the mule.

But if it hadn’t been for the mines, Webb never would have become a baseball player.

“I didn’t begin to play baseball until I was about 12 years old, maybe 13,” he remembered later, “when the mine doctor advised me to get exercise and fill my lungs with fresh air after breathing coal dust all day.”

Webb became a pretty good pitcher, he could throw a very fine curve ball. The only day of the week he wasn’t underground was Sunday, and soon local teams were paying him to start their games on the Sabbath. His skill with a baseball was a ticket out of a life in the coal mines. His father was a miner, and so were his uncles. His grandfather had went to work for decades deep in holes beneath Tennessee. Webb wanted to find another way to make a living.

Webb was a shy kid. As he got better as a pitcher, he was offered jobs with mine teams in bigger towns. He took the money and moved, but he didn’t like city life. He got so good that a scout for the New York Giants offered him a guaranteed contract, but Webb refused because he was petrified to go to New York City. Eventually, the scout assured Webb that there were other “greenhorns” in the major leagues, and that he could latch on to them.

It was the 1920s when Webb arrived in New York for his first taste of the Big Apple. The story goes that on one of his first days in the city he was staring up at a large building when he walked into a stranger.

“Watch were you’re going, kid,” a voice boomed at him.

It was a familiar face, one he’d never seen with his own eyes, but one he’d seen in photographs.

“Aren’t you Babe Ruth?” the timid Webb asked the strange man.

“Yes,” the great Bambino replied.

“I’m trying to find the Polo Grounds,” Webb told Ruth. “Do you think you can help me locate it?”

“I’ll do one better!” Babe said. “I’ll drive you there in my car.”

Webb didn’t impress the Giants enough to earn a roster spot as a pitcher, but he had a guaranteed contract, so they sent him to the minors to work his game out. It was in Pittsfield, Massachusetts that he started to play the outfield. Later he smashed up the league with his hitting in Toledo, and the Giants brought him back for a quick trial in 1925.

Over the next few years, Earl wore himself out putting stickers on his travel trunk: he played for no fewer than five teams in four different minor leagues. The Reds bought him, sold him to the Cubs, the Cubs sold him to the minor leagues, and then he briefly bounced around, unwanted.

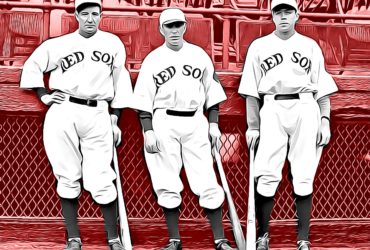

The Red Sox were a terrible team in the 1920s and they hoped the 1930s could be better. They didn’t have anything to lose, so they signed Webb in 1930 and made the 32-year old their starting right fielder. It was a bad team, but for Earl it was a helluva lot better than digging coal out of the ground.

Webb was a tall, strong left-handed batter. He had strong arms and wide shoulders. He had bushy eyebrows and dark, wide-set eyes. He was extremely shy and he had few close friends on the Red Sox. On road trips he took a train or taxi from the ballpark after games and remained in his room. He was not a man who wanted to see the city. It was said that after the season ended, only moments after the last out was recorded, Earl was packed and on a train back to the mountains of Tennessee.

In 1931, Webb had his season for the ages. In order to hit 67 doubles, a player needs to (1) play a lot of games, and (2) hit a lot of balls into the gaps or down the lines. Webb was a good pull-hitter, but he also hit a lot of long flies to center field. The Red Sox played at Fenway Park, one of only two major league parks in use in 1931 that still hosts baseball today. The right field line was short, just as it is now, and Earl hit a lot of balls down the line. He hit 39 of his doubles at Fenway.

Webb hit five doubles in his first ten games and went from there. He had 16 doubles in May and 18 in July. He went two weeks without a two-bagger in August, but then he got hot again, and entering the final month of the season he had 54, ten behind the record, held at that time by George Burns (the baseball player, not the comedian).

The Red Sox had a 23-game homestand in September (like I said, these were different times). Webb hit six doubles in a five-game span and broke the record in Game #144. The record breaker went to the opposite field. But there was no “Green Monster” out there for Webb to smack the ball against. The famed Fenway left field wall wasn’t built for three more years, and it wasn’t painted green until after the second World War.

For his achievement, the press named Webb, The Earl of Doublin’, one of the campiest nicknames to be lost to history.

The Red Sox traded Webb the following season after he got off to a bad start. He was dealt to Detroit, and true to form, his first two hits as a Tiger were doubles. He was mustered out of the league a few years later, his legs and bat having slowed. Earl was never a good outfielder, and by the time he was in his late 30s, he had the range of a cement block. He hung around the bush leagues before returning to east Tennessee. Ironically, Webb ended up returning to the coal mines, working as a mine manager up until his death at the age of 67 in 1965.

How did Earl Webb hit so many doubles? Boston manager Shano Collins, whom Earl credited with making him a good hitter, had his theory.

“The reason he hits so many doubles, is that he hits a long, hard ball and he’s too damned slow to make it to third!”