On a day when the New York Yankees will play a must-win game in their Division Series against the Tampa Bay Rays, the most important big game pitcher in franchise history has passed away.

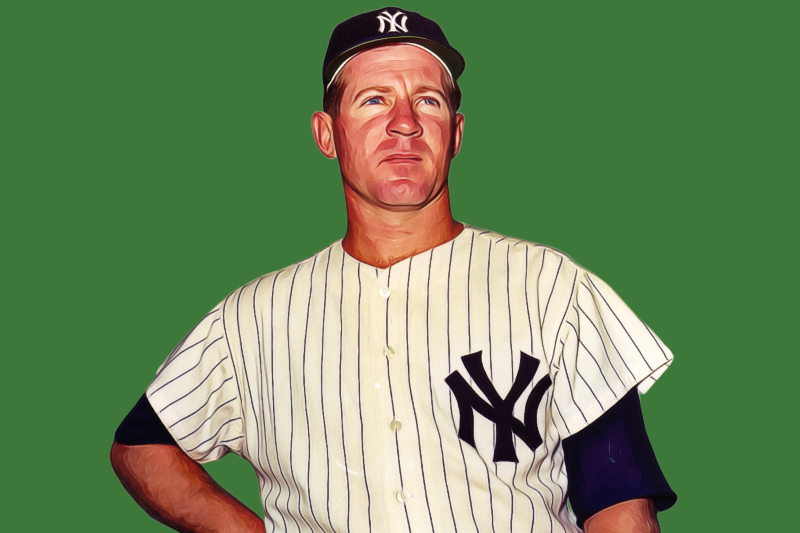

Hall of Fame pitcher Whitey Ford has died at the age of 91. The news of his death dampens baseball’s postseason, and it comes on the heels of the losses of three other great baseball legends within the last six weeks. Tom Seaver died on August 31, followed by Lou Brock a week later on September 6, and Bob Gibson died on October 2.

Ford was the oldest living Hall of Fame player before his death.

Ford pitched for the Yankees from 1950 through 1967, winning 236 games. His .690 winning percentage is one of the highest in history. He added 10 more victories in the World Series, and he was named Most Valuable Player of the 1961 World Series.

Ford’s New York roots ran deep: he was born in New York City in 1928. He was raised on 66th Street in Manhattan before his family moved to Queens. His childhood idol was Joe DiMaggio. When Ford made his big league debut in 1950 at the age of 21, DiMaggio had three hits to support his new teammate. That fall, Ford started and won Game Four, the clinching win in the World Series. It was the first of six championships the Yankees won with Ford in their rotation.

Whitey was a favorite of his manager, Casey Stengel, who quickly surmised that the young lefthander was unfazed by the bright lights of big games. But the Yankee manager also wanted to preserve the little southpaw. Casey felt Whitey was too small to withstand the burden of a heavy workload and he also wanted to save Ford, using him in the most important series. For about seven years, Whitey started 5-6 fewer games each season under that conservative plan. He typically squared off against the Indians and White Sox, the two chief rivals for the Yanks in the 1950s. Whitey went 69-35 in his career against Chicago and Cleveland.

In 1961, under new manager Ralph Houk, Whitey started every four days for the first time and responded with 25 wins. The lefty averaged 37 starts and 20 wins from the age of 32 to 36, thriving under a heavier workload.

Ford pitched in 11 World Series for the Yankees from 1950 to 1964. He was tapped to start Game One eight times, and twice he started three games in a single series. He was trusted by Stengel and Houk to take the ball when the most was at stake.

“I know when he’s on the mound I have a chance to earn that [World Series] share,” teammate Billy Martin once said.

“You kind of took it for granted around the Yankees that there was always going to be baseball in October,” Ford said.

Early in his career, Ford missed two full seasons while he was in the Army during the Korean War. He loved to downplay his military career, seeing as he spent much of his stint pitching for an Army team.

“Army life was rough,” Whitey said. “Would you believe it, they actually wanted me to pitch three times a week.”

Ford was also famous for using a spitball on occasion, especially as he aged.

“I didn’t begin cheating until late in my career, when I needed something to help me survive,” Ford admitted. “I didn’t cheat when I won the twenty-five games in 1961. I don’t want anybody to get any ideas and take my Cy Young Award away. And I didn’t cheat in 1963 when I won twenty-four games. Well, maybe a little.”

At the start of the 1960 season, 31-year old Ford had been an All-Star numerous times and a postseason hero. But he still had trouble with his control and the command of his fastball. When he needed to get out of trouble, he would slip in a wet one. Ford had his best seasons after Eddie Lopat became pitching coach and he won his only Cy Young Award in 1961 when he won 25 games and struck out more than 200 batters for the first time.

Another aspect of Ford’s persona was his relationship with Mickey Mantle, his best friend. Ford and Mantle struck up an unlikely bond: Whitey a slick New York kid and Mickey a “country bumpkin” from Oklahoma. But they loved to frequent restaurants and night clubs and burn the midnight oil. In 1957, Ford was at the center of the famed Copacabana night club fight that involved Mantle, Martin, and several Yankees.

Ford’s nickname was “The Chairman of the Board” because of his slick style of dress and calm, classy demeanor. He was revered by his teammates as a cool character.

“I don’t care what the situation was, how high the stakes were,” Mantle said. “The bases could be loaded and the pennant riding on every pitch, it never bothered Whitey. He pitched his game. Cool. Craft. Nerves of steel.”