This is the second article in a series on baseball style that we call “Fashion Plate.”

When we look back at the 1970s there’s a lot to love about baseball during that period: new ballparks and astro turf, the emergence of the designated hitter, and Monday Night Baseball.

There were great teams too. But oddly the team most associated with the decade, the one that gets talked about the most, is the Big Red Machine, or the Cincinnati Reds of the Pete Rose, Johnny Bench era. That team is considered by many to be among the greatest of all-time. The 1970s Yankees, of Billy Martin and Thurman Munson also get a lot of books written about them, and deservedly so. But there’s another team that deserves a closer look, one that outperformed the Reds and the Yankees in the 1970s.

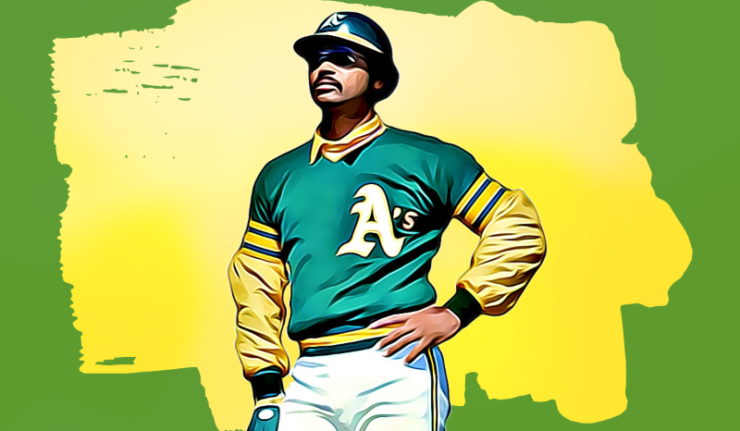

The Swingin’ A’s of the 1970s changed baseball while dominating the game. Led by maverick owner Charles O. Finley, and starting as second-fiddle to the Giants in the San Francisco Bay Area, the Oakland A’s won three straight World Series titles from 1972 to 1974, and they looked good doing it.

Three Straight Titles in Oakland

In all of baseball history, only four times has a team won as many as three consecutive World Series titles. The Yankees have done it three times: from 1936-1939, from 1949-1953, and again from 1998 to 2000 at the close of the last century. Only one other franchise has accomplished this rare feat: the Oakland A’s.

In 1972, again in 1973, and finally in 1974, the A’s dominated baseball by winning three straight Fall Classics. The team was built through the guile and acumen of owner Charlie Finley, who was for a long time one of only a handful of front office employees, and the only one making baseball decisions. Finley drafted wisely in the 1960s and early 1970s, and he scouted players near and far. He landed pitchers Jim Hunter and Vida Blue, who served as the axis of a fantastic pitching staff. He drafted Reggie Jackson and Rick Monday from Arizona State University, and he shepherded gritty, broad-shouldered Salvatore Bando into his organization. Bando would serve like a manager on the field, helping the wild A’s stay focused on the task at hand: winning.

For five seasons, from 1971 to 1975, the A’s won the division title and advanced to the playoffs. Relying on a deep pitching staff, solid defense built on team speed, and a steady offensive attack, the A’s won the World Series in 1972 and 1974 in seven games, constantly edging opponents in tight, hard-fought games. In their three World Series triumphs, nine of Oakland’s 12 Fall Classic victories came by one run. The A’s could beat their opponents in many ways, and any slip by the other team could spell doom.

The 1972 World Series was notable because the A’s matched against the Cincinnati Reds, one of baseball’s most conservative organizations. The Reds didn’t like individuality and self-expression, demanding their players wear their hair neat with no facial hair, and their uniforms trim and proper. Black belts, black shoes, and short sideburns were the order for the Reds. The media dubbed the 1972 Series as “The Hairs vs. The Squares.”

The Mustache Gang

One of the most indelible things about the Oakland A’s of the 1970s was the real estate under their noses and above their lips. Their audacious embrace of the groovy 1970s made them a team for the ages. At the time it was revolutionary.

As the 1970s dawned, no big league player, not a single one, had worn a mustache in the major leagues for about 35 years. The last player to do so only did it because it enabled him to make some money in his side hustle.

Stanley “Frenchy” Bordagaray was a mediocre (maybe even disappointing) third baseman in the 1930s and 1940s for several teams. Before he sported a “soup strainer,” Frenchy was best known for his wild antics chasing women off the field and throwing the baseball eight feet over the head of his first baseman from across the diamond. During the 1935-36 offseason, Bordagaray grew a thin mustache for a bit role in a film called The Prisoner of Shark Island, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, and directed by John Ford.

“I was making $3,000 a year playing baseball, so I figured I could at least have fun while I was not getting rich,” Bordagaray said. “But after I had [the mustache] about two months, [manager] Casey [Stengel] called me into the clubhouse and said, ‘If anyone’s going to be a clown on this club, it’s going to be me.'”

After Casey forced Frenchy to trim his facial hair in 1936, no major leaguer dared wear a mustache in “America’s National Pastime.” Until a slugging member of the A’s decided to break the “hair barrier.”

When he arrived for spring training in 1972, outfielder Reggie Jackson was sporting a mustache he had let grow all winter. Thinking Reggie would have to shave it before opening day, a few Oakland players decided to test the waters and grew their own. That group included pitchers Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Darold Knowles, and Rollie Fingers. Somewhat surprisingly, owner Charlie Finley liked it, and offered his players and coaching staff $300 to grow a mustahce for the start of the season. An extra $300 was attractive to the chronically underpaid A’s, and almost every man on the roster took the offer. Relief pitcher Rollie Fingers grew a handlebar mustache, and he wore it the remainder of his career. He even retired rather than spend his final season as a member of the Reds, who required a clean-shaven face.

In 1972 with all their new facial hair, Finley and the A’s held a “Mustache Day” at the Oakland Coliseum and invited Frenchy Bordagaray, the last big leaguer to have worn a mustache during the regular season.

The Kelly Green Machine Is Born

The team owner abandoned the traditional red, white and blue that had adorned uniforms in Philadelphia and went to a tri-color format. In true “Charlie O” fashion, he called the colors:

- “Kelly” Green

- “Wedding Gown” White

- “Fort Knox” Gold

Why “Kelly Green”? Because Kelly is a common Irish name and green is the color of the Irish, and Finley’s father came from Ireland to America. Wedding gown white was supposes to appeal to female fans, and Fort Knox gold, well that was just a wink at the big money Finley hoped to make with his newly dressed team.

With their dynamic green, yellow, and white color scheme, the A’s pushed the style envelope even further by mixing and matching the ensemble. At this same time, in the early 1970s, polyester was being used for the first time in uniform design.

For decades, dating back to the Victorian Age, baseball teams made their uniforms out of wool. Why? Because wool was heavy and durable. Teams didn’t want to replace uniforms often, and in fact in the early days many teams didn’t even want to wash them that often. Wool was rugged, if not comfortable.

“I used to lose five pounds wearing those [wool uniforms] during a doubleheader,” Al Kaline said of his early years in the big leagues.

With the lone exception of the Dodgers briefly using satin to make uniforms for night games, wool was the only fabric used for baseball until the 1970s season. That year, the Pirates debuted polyester uniforms after the All-Star break, in part to celebrate the opening of their new ballpark, Three River Stadium.

The A’s had Kelly Green and “Fort Knox” yellow polys the following season, mimicking the Pirates pullover style tops and also eventually adding a multi-color elastic waistband.

With yellow and green stripes on their sleeves as well as a green-and-yellow accent stripe on the side of their pants, the Oakland A’s debuted in 1971 with what would become an iconic uniform in their championship era.

There were a myriad of combinations possible:

- Green jerseys and white pants

- Green jerseys and yellow pants

- Green with green (either with sleeveless vest tops of traditional jerseys)

- Yellow jersey white white pants

- Yellow jerseys and yellow pants (yes, they actually did this on a few occasions)

- White jerseys with white jerseys

It wasn’t just the mix-and-match tops and pants that made the Oakland A’s the fashion icons of the 1970s. They also introduced elements like white shoes and a special cap that was worn by coaches.

Finley had made his team wear white cleats in the 1960s when the franchise was still in Kansas City. But the white shoes may have been a bit too hip for Missouri. When his team relocated to Northern California for the 1968 season, Charlie knew the white shoes were going to make his team stand out.

In 1972, Charlie ordered his manager and coaching staff to wear white hats, in contrast to the green caps his players were wearing. This was the first time in modern baseball history that a team had special head ware for the coaching staff.

The End of an Era

All good things must come to an end. The A’s couldn’t win forever, and given their tumultuous clubhouse (Reggie and teammate Billy North engaged in a famous fight in Detroit), and the yearly struggles by players to get a raise from skinflint Finley, it was only a matter of time before The Swingin’ A’s were split up.

Free agency and the changing economics of baseball made it harder for hands-on smaller market owners like Finley to survive. In 1976, the A’s sold or traded most of their stars, and within a year they were in last place. Finley sold the team in 1980, just as a new group of players that he and the front office had scouted and signed, were coming to maturation. This Sports Illustrated cover from 1981 shows the A’s talented starting rotation, still clad in Kelly Green and Fort Know Yellow.

The Return of the Green

In 2018, on the 50th anniversary of the team moving to the Bay Area, the Athletics reintroduced the Kelly Green to an alternate uniform. The design was different (instead of the large white “A’s” patch on the left breast it featured a white script “Oakland” across the front), but the colors were a match for the Reggie/Catfish era.

“It’s already become my favorite jersey,” said third baseman Matt Chapman. “I could be biased because I’m wearing it right now but I love the colors, I love everything about it, it’s got that old school look to it.”

Somewhere, Charlie Finley, who died at the age of 77 in 1996, must have been smiling.