Tenney was a catcher and an outfielder, but he settled at first base more out of team necessity, because Boston had great outfielders. He was a fantastic first baseman, according to contemporary reports. He was small, even for his era, and very quick. He apparently wandered far to his right to field grounders and was skilled at fielding the bunt. He also had a catcher’s arm. He set records for assists by a first baseman that lasted a very long time.

Rare was it for a college graduate to make his way to the professional baseball ranks in the late 19th century, when Fred debuted with the Beaneaters after attending Brown University, a private institution in Rhode Island. Tenney was smart, and he was a confident man even at a young age. He assumed a leadership role under the guidance manager Frank Selee, for whom Fred played for eight seasons. Boston won two National League pennants in the late 1890s with Selee and Tenney serving as the manager and team captain.

As a hitter, Tenney was sort of a Mike Hargrove type: a left-handed contact hitter, high average with modest power. Like Hargrove, Tenney walked quite a bit and he could also use the entire field. He never won a batting title, but Fred finished in the top ten three times, and he was in the top ten in bases on ball six times.

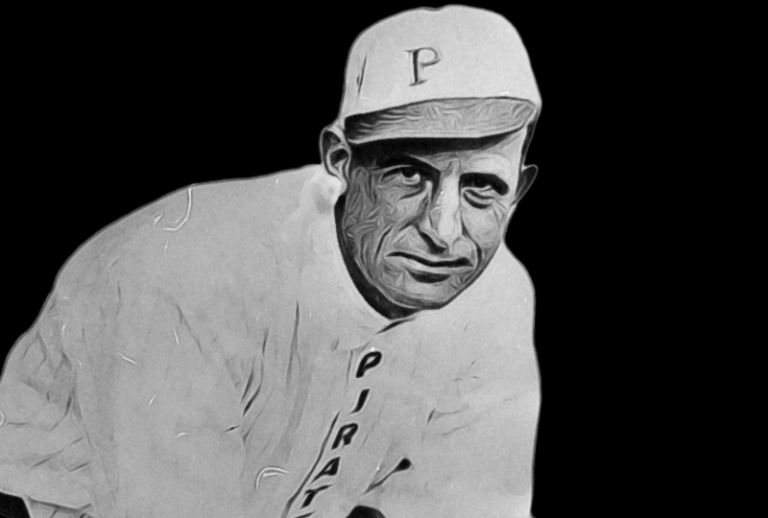

Bitter Enemies: Fred Clarke and Fred Tenney

One of the fun things about diving into baseball history is finding stories that humanize men who are now only numbers on a career record to us. For Tenney, it’s interesting to note that he had a running feud with Fred Clarke, the outfielder who had an eerily similar career path. Both Tenney and Clarke debuted in 1894, the former with Boston, the other for Louisville. Tenney was 11 months older than Clarke, but they played almost exactly the same number of years and must have faced each other hundreds of times. Clarke played from 1894 until 1911 (he made token appearances after that but he was really just a manager by then), and Tenney also played from 1894 to 1911. They became quite familiar with each other, and as they say: “familiarity breeds contempt.”

By 1901, Clarke was with Pittsburgh as player-manager when his Pirates faced Tenney and the Beaneaters at home. In that game, the Pirates pitcher plunked several Boston batters and the Boston pitcher retaliated, and so on. The benches cleared twice, and the last time, Clarke and Tenney found themselves toe-to-toe. Tenney attacked Clarke, who responded by wrestling Red to the ground where they bruised each other until teammates separated them. “Clarke called me names, then I twisted his nose, and he kicked me in the stomach,” Tenney said. His actions led to a 10-game suspension and a $75 fine. But the two rivals were not finished.

In 1905, Tenney was elevated to Boston’s player-manager. Clarke was still in that same role for the Pirates, which meant that for the next three years while Tenney was Boston’s skipper, the two men faced each other 22 times a season. The Pirates were a great team at that time, and Clarke was their star left fielder. The Boston Doves (or Beaneaters or whatever name a newspaper would call them at the time), were a bad team, and Tenney suffered the many losses that he took personally. One chance he had to take out his frustration was to make life miserable for Fred Clarke. In his first season at the helm, Tenney’s Boston club went 9-13 against Clarke and his Bucs. That doesn’t sound too good, but the Pirates were a 95-win team, and Tenney’s club lost 103 games. The next season things got more interesting.

In 1906, Clarke’s Pirates beat Tenney’s Doves 19 out of 22 times they met. That’s not a rivalry any more than the nail has a rivalry with the hammer. But within those 22 games, Tenney made sure his pitchers threw at Clarke and his star players as often as they could. The two men apparently still hated each other going back to their brawl in 1902. In July in Pittsburgh, Tenney got so fed up with losing to Clarke’s team (and sick of hearing Fred heckle him) that he went into the visitor’s dugout at South End Grounds in Boston and argued with the opposing manager. Things got so bad between the two men and their teams that National League president Harry Pulliam called them to his office to clear the air. I’m not sure if it helped, or if the two Fred’s ever shook hands and buried the hatchet. Clarke got the last laugh (so to speak): he outlived Tenney by eight years and he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.