Let him hit it. You’ve got fielders behind you. — Alexander Cartwright, baseball pioneer

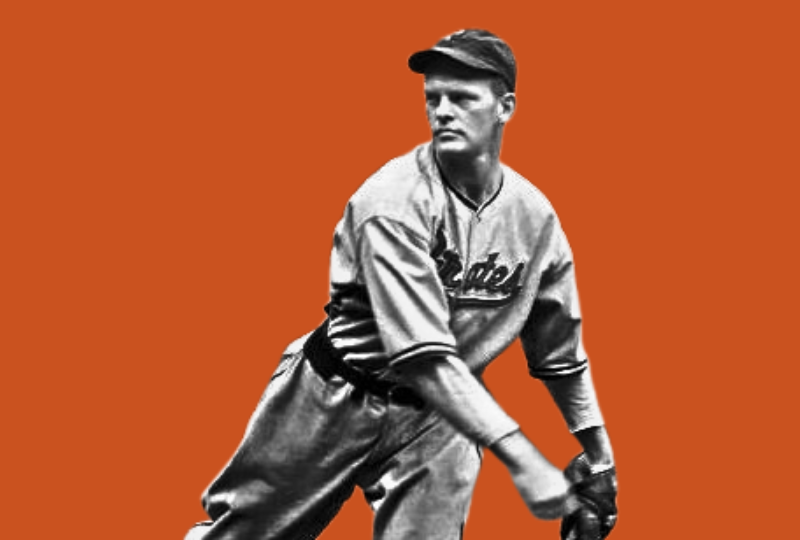

The purest junk — the junkiest pitch in history — is the Eephus pitch, invented by Rip Sewell of the Pittsburgh Pirates in the thirties. The Eephus pitch is a pitch with absolutely nothing on it — no velocity, no fancy spin, and no break. No deception at all. And most of all, no SPEED.

It’s an American Gothic, a true Mother-Hubbard’s-bare-cupboard of a pitch. Every once in a while, Sewell would just look at the plate, and lob the baseball up into a rainbow arc. There was no ulterior motive here. No trick. It’s the same pitch you see on a slow pitch softball field, only overhand, and higher, and, somehow, even slower.

Sometimes, the ball dropped down into the strike zone while the suddenly emasculated hitter flailed. More often they managed some kind of contact, yet for some reason (perhaps arc of the pitch was too severe) they couldn’t knock it out of the park. And that’s all they wanted to do. As a hitter, you don’t see an outrageous pitch like the Eephus and think, Single. The Eephus pitch was an insult: they wanted to pulverize it, kill it, crush it. They’d get so worked up waiting for it they couldn’t see it straight, and they’d ground out, or pop out, or miss altogether. They risked injury — the swings they took where that hard. And then they were embarrassed, angry. Give it to me again, you son-of-a-bitch! But … no. Probably not, not for you. Not any time soon. Batters would wish for another chance they might not get for a year, but the pitch would be in their minds every time they faced Sewell — that big looping marshmallow of a pitch. It was galling, an itch they couldn’t reach, an ache. Sewell was careful not to throw the Eephus too much — he tried to keep it around 10 times per game. He wanted hitters to hope for it, but he wanted its arrival to be unexpected, every time. This made all of Sewell’s other pitches look a little bit better, because any pitch, any pitch at all, looks fantastic when compared to to the Eephus.

Fans loved it: the game became a giant jack-in-the-box, wound tighter and tighter. When would it come? Pitch after ordinary pitch would zing by, When would it come? , and then (not suddenly … anything but suddenly) the pitch would rise up. Fans gasped. It was like a firework, lobbed high. OOOOOhhhh. And then, during the descent, everyone would wait for the explosion. But all they heard was the anti-climactic clunk of the bat awkwardly meeting the ball. A ground out, a pop out … anything but a home run.

Like all good junkballers, Sewell was an excellent fielder (he once made three assists in the same inning) and he figured if he kept the ball inside the park, he’d done his job; his teammates could do the rest. It worked. In Sewell’s 13-year career he had 11 winning seasons, giving up fewer than one home run every 18 innings, a remarkably low rate for anyone. And, shockingly, he only gave up one home run ever off the Eephus pitch. It was during the All-Star Game of ’46, and Sewell had a sore arm. He didn’t think he’d pitch. But the game turned into a blowout, and the manager asked him to go in, put on a show. By this time in his career, Sewell had appeared in over 300 big-league games, and had yet to give up a homer off the Eephus. The fans wanted to see the pitch, and the batters probably wanted to see it even more. Ted Williams already had one home run in the game, and wanted another. The game was in Fenway, and he wanted to show something to the hometown fans. As he stepped in, he looked out at Sewell and hollered (hopefully?), “You’re gonna throw that damn pitch of yours, aren’t you?” Sewell admitted, smiling, that he just might. Williams missed the first one badly, but, in a fit of hubris — the one thing no junkballer can afford — Sewell announced that he would throw another. “Here it is again,” he said … the words barely out of his mouth when Williams knocked the ball as far it could possibly travel. Years later, Williams admitted his secret. He’d cheated. As Sewell threw, Williams ran forward to meet the ball. Photos reveal that he is a few feet in front of the batter’s box when his bat hit the falling ball.

Catnip for Johnny Mize

From time to time, this Eephus pitch has slipped out of other pitchers’ hands. Vito Tamulis, an otherwise unknown left-hander for the Brooklyn Dodgers, used a principle opposite of Sewell’s. He announced the pitch, and reserved it for a select few good hitters with quick bats … often for the great Johnny Mize. Tamulis was a very heavy player (at 5’9’’, he weighed, at times, over 190 lb, it was a struggle for him to stay under 180) and he was anything but intimidating. He was rotund, and he was a junkballer — good control, no fastball. As a lefty, he was often called on to face the left-handed Mize. Tamulis would walk halfway in toward the plate and announce that he was going to throw a rainbow change: Here, hit this, you big stiff.

Mize (the original “Big Cat”) had an incredibly quick bat. He pulled everything, even the best fastballs. His bat was so fast, it could be almost a weakness, and against Tamulis it was a weakness. He would nearly kill himself trying to hit this garbageball from a pitcher who was not quite marginal.

Steve Hamilton (a 6’6’’ reliever for the Yankees who had played basketball with the Lakers) threw a similar pitch in the sixties. His was called the Folly Floater, and it was remarkable only because it started at such a great height. “The Spaceman,” Bill Lee, also threw a somewhat similar pitch in the seventies; he called his a “Bloop Curve.” The “Bloop Curve” met a tragic end, however, in Game Seven of the 1975 World Series. Lee had, earlier in the series, retired Hall of Famer Tony Perez with the blooper. In fact, he had done it twice, but this time Perez waited, then waited, then hit a titanic, game-winning, series-winning, home run. Goodbye, baseball and welcome back, curse. Perez hit the ball so hard the Red Sox outfielders didn’t even turn around to watch it travel.

The Birth of the LaLob

In the 1980s the Eephus pitch made a triumphant return in the form of “LaLob”. LaLob was the creation of reliever Dave LaRoche. One reason for LaLob’s fame might have been the fact that LaRoche had once been a dominating reliever. In his prime, he was a two-time all-star, with over 100 saves. But, late in his career, he became an underdog. His fastball was gone. Fans love an underdog, and, toward the end of his career, LaRoche began to throw the ultimate underdog pitch. It was easy on his arm, and fans adored it. Like the other pitchers who used the pitch, LaRoche used it very sparingly — maybe five times for every nine innings he pitched, reserving it, for the most part, for sluggers. During one particular 1985 game versus the Brewers, he decided to test the limits of LaLob.

The situation called for an intentional walk: two outs, runners on second and third, and slugging Gorman Thomas at the plate. Yankee manager Bob Lemon came out to the mound, intending to call for the walk; it would set up a force play everywhere, and would get the dangerous Thomas out of the way. LaRoche, however, had another idea. Gorman Thomas, was a “pure” power-hitter, which is another way of saying his swing was profoundly impure. A two-time AL home-run king, Thomas also sported a minuscule career batting average (.225). He had a huge swing, and if (big “if”) he hit the ball, it traveled. Like LaRoche, he was at the tail end of his career in ’85.

LaRoche thought he saw an ideal set of circumstances: the giant, slugger’s swing; the potential RBI situation; the raw, terrified pride of an athlete at the end of his rope. Thomas was primed. LaRoche told Lemon he wanted to throw four straight LaLobs. Lemon, a Hall of Fame pitcher, with a Hall of Fame imagination, said, Well, why the hell not?

The Yankee Stadium fans, expecting a walk, roared when they saw LaLob … it missed, outside, for a ball. Thomas connected with the second one, but knocked it foul. Thomas looked back at the catcher, said, “He’s gonna throw that goddamn thing again, isn’t he.” The catcher could say, honestly, that he had no idea. On the third pitch, Thomas did something unprecedented. He tried to bunt LaLob. No one had ever tried this, not against the Eephus, the Folly Floater, and not against LaLob; certainly not a two-time home-run champion, certainly not with two outs, and most certainly not with two men on base. The ball went foul for the second strike. LaRoche (perhaps feeling that he was tempting the fates, or risking murder at the hands of Thomas) tried an honest fastball, but missed outside. With a 2-2 count, LaRoche threw a fourth LaLob, and Thomas took a violent, uncontrolled swing. He missed, badly, and in so doing, lost his balance and landed right on the seat of his pants. He then took off his helmet, tossed it up, and shattered it with his bat. It was the first thing he had hit solidly all day.

Soft Tossin’

Sewell rode the Eephus pitch, and the rest of his repertoire, to a 143-97 lifetime record. He won 20 twice, and in 1943 led the league in complete games with 25. In the seven seasons between ’39 and ’46, Sewell averaged over 200 innings per year.

And the Weak Shall Be Strong

In an instance of poetic justice, the Eephus pitch worked best against sluggers … a fact Bob Tewksbury knew very well. When you aren’t blessed with the sort of fastball that scares people, it pays to know a little history, and Tewksbury (a wily pitcher who went to college after he played ball) decided to unleash the Eephus vs. the mighty Mark McGwire in 1997. He had never tried it in a game, but he tried it against Big Mac twice. Mac’s eyes lit up like he’d seen the future … a brief home-run trot … but he merely grounded the pitch to second base. Later in the game, Tewks tried it again, and McGwire grounded out again.