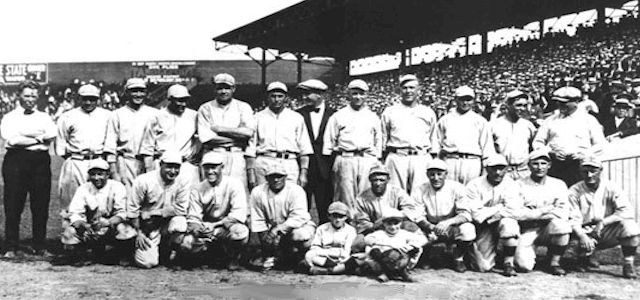

The 1918 baseball season was unusual in many ways because it was an unusual period in American history. For the first time, the nation was in a worldwide war, and games didn’t seem all that important.

As the baseball season ended in 1918, the Great War was winding down on mainland Europe, but the impact it had on baseball was still very evident. By order of the U.S. government, the regular season had been halted on September 1 due to the “Work or Fight” edict. Able-bodied American men were expected to either serve as soldiers or work in war-related industries. The fight for the pennant may have seemed like a war, but it wasn’t nearly as important or as dangerous as what was raging in Europe.

Want to know how different hings were back then? The President of the United States was an intellectual scholar, the Boston Red Sox won the AL pennant, and the Chicago Cubs won the flag in the National League. It was like Bizarro world.

To reduce travel expenses the series was scheduled for three games in Chicago and the final four in Boston, so the teams would only pack themselves on to trains once. For the Series, the Cubs played their games at Comiskey Park, the home of the crosstown White Sox. Why? Because Comiskey Park could accommodate more fannies than tiny Weegham Park, the home at that time of the Cubs.

In Game One, during the seventh inning stretch, a band played “The Star Spangled Banner” – the first time the song had been played at a ballgame. It would be several years before it became commonplace to play the song prior to each baseball game, and several more before the U.S. made it the national anthem.

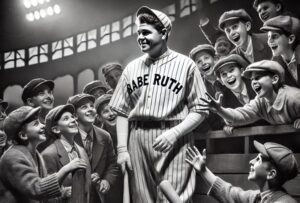

With their superior pitching staff, Red Sox took two of the three games in Chicago. They won Game One behind a tall, still slim left-hander named George “Babe” Ruth. Ruth twirled a shutout to start the series, and two days later Carl Mays, one of the nastiest pitchers of that era, won Game Three, 2-1. That contest ended in dramatic fashion when the Sox tagged out a Cub player who was trying to score on a passed ball in a rundown between third and home. The groans of the Chicago faithful could be heard in the stands.

Not much changed when the two teams met in Boston. Ruth again toed the rubber and this time he held the Cubbies scoreless until the eighth inning when they plated a pair of runs. That ended the Babe’s shutout streak at 29 2/3 innings, still a World Series record. It’s worth noting that Ruth hit sixth in the lineup – he’s the only pitcher to ever bat anywhere other than ninth in a World Series game. Boston and the Babe won that contest and were one victory away from clinching the championship. But there wasn’t a lot of joy in the clubhouse on either side.

Game Five was slated to start in the early afternoon on Thursday, September 10. As close to 25,000 fans sat anxiously in their seats at Fenway Park, they started to notice something odd – there weren’t any players anywhere to be seen on the field.

That was because the Cubs and Red Sox players had decided to make a statement. Throughout the Series there had been grumbling from both sides. The players weren’t happy about the split of the gate receipts. They were dissatisfied with a new rule that took a portion of the profits from the Series and gave them to third and fourth place clubs. They weren’t happy that the team owners seemed to get richer and richer while they were required to take less of the money from the game’s biggest showcase. It was years before there would be a player’s union, but for as long as people have been working at any job, there has been griping and dissension, especially when it comes to money.

The crowd began to get restless, most of them unaware what was happening. Some of the players weren’t even in uniform, and it was minutes before game time. The umpires were powerless to do anything and they simply huddled on the field. That’s when Ban Johnson, the immovable force that was the American League, arrived on the scene. Baseball was a few years away from having (or even needing) a commissioner, but Johnson, as President of the AL, was essentially THE power in baseball.

Johnson was met by Harry Hooper, representing the Red Sox, and Les Mann, speaking for the Cubs. The two players were overmatched by Johnson’s personality. When Johnson looked them in the eye and asked them if they wanted to let down the fans who were there to see baseball’s greatest spectacle as the country fought for democracy, Hooper and Mann retreated from their stance.

The clubhouses emptied and the game was played. The Cubs won behind a masterful shutout performance from James “Hippo” Vaughn. But the following afternoon, September 11, 1918, the Red Sox vanquished the Cubs by the score of 2-1, winning their fourth title in seven years. It would be the Sox last title for 86 years, and the Cubs are still waiting to win another.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-1940s that a serious effort would be made by players to form a union, and they wouldn’t succeed until 1953. In the mid-1960s they hired Marvin Miller as their leader, and within a few short years the MLB Players Association was one of the most powerful unions in the country. That sort of clout would have been welcomed by Hooper, Mann, and the members of the Red Sox and Cubs in 1918, when the two pennant winners nearly went on strike during the World Series.