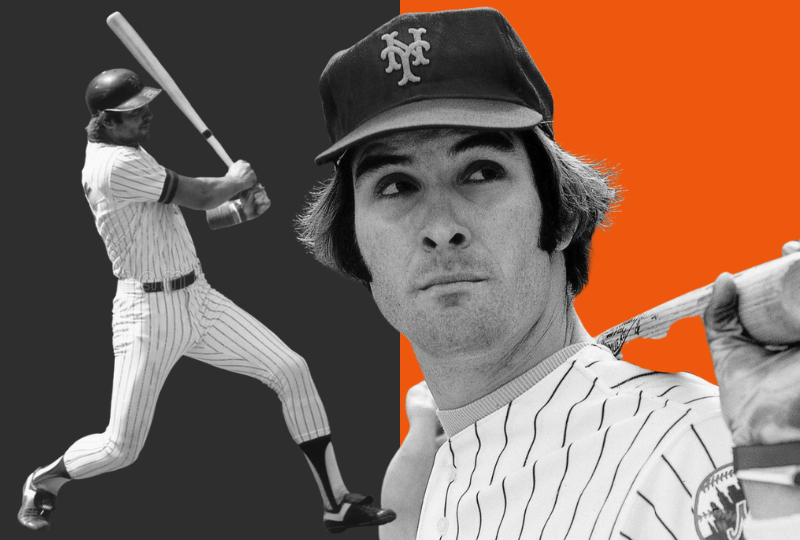

No history of expansion era baseball can be told without mentioning the career of Dave Kingman, a troublesome ballplayer who usually elicited two types of reactions: awe! or ugh.

When he was finally expelled from Major League Baseball, Kingman had hit more home runs than all but 18 players in the history of the game. But his legacy was less about the swings that sent a baseball over fences, and more about his swings that met air. He retired with the fourth-most strikeouts ever. The whiffs, low batting average, and disdain for sportswriters brought him more headlines than his tape-measure home runs.

An Oregon kid, Kingman was recruited as a pitcher by Southern Cal, where he went 11-4 with a 1.38 ERA as a sophomore for legendary coach Rod Dedeaux. But in batting practice, Kingman amazed his coach and teammates with the distance and the height of his home runs. He hit four home runs in only 32 at-bats as a freshman pitcher. The Trojans moved Kingman to the outfield for his sophomore season, where he had nine homers and 23 extra-base hits in 32 games. Early in that season, in 1970, the Trojans played a three-game series at Dodger Stadium. With more than 20,000 spectators taking in the games, Kingman put on a show of power: a 450-foot home run and five doubles. Southern Cal won the College World Series, and from that point on, Kingman was on the radar of every big league club.

The Giants made Kingman the #1 pick in the 1970 MLB Draft. He reported to Amarillo, where he tore up the Texas League, swatting 15 homers in 60 games. His teammates nicknamed him “Hammer” because he hit the baseball so hard.

When Kingman was a prospect, he was an awkward-looking athlete: 6-foot-6 inches with a slim waist; weighing about 200 pounds; skinny ankles; big feet; and a long neck. He looked like he was all legs and shoulders. His first minor league manager, Rosy Ryan, noted Kingman’s athleticism. “He’s the fastest runner on the team, has the best arm, and he’s one of the strongest men I’ve ever seen,” Ryan said. “He has a chance of becoming one of the game’s great sluggers.” Ryan would know slugging: he had once been Babe Ruth’s teammate.

In 1971, Kingman was assigned to Phoenix in the Pacific Coast League. The big right-handed swinger showed that he was the class of the league with 26 home runs and 99 RBI in only 105 games. The Giants couldn’t keep “Hammer” on the farm any longer, and he was summoned to the big leagues at the end of July. In his second game, Kingman pinch-hit for Willie McCovey in the fourth inning and smacked an RBI-double. In the seventh, he hit a grand slam off Dave Giusti. The ball soared 15 rows into the left field seats at Candlestick Park. The following day, in the second game of a doubleheader, with McCovey resting, Kingman batted cleanup and played first base, and hit two home runs off Dock Ellis. The next time he started a game, he produced another home run, that time playing right field.

The Giants roster was packed with potential in 1971. The 25-year old Bobby Bonds was in the outfield, and 25-year old left fielder Ken Henderson was emerging. McCovey was in his prime, and a skinny 22-year old outfielder named George Foster was lurking. The team had a superb rookie shortstop in Chris Speier. The great Willie Mays was still in uniform, and manager Charlie Fox needed to find playing time for all his talent. Kingman was shuttled between first base and corner outfield to get his booming bat into the lineup. In 41 games, Kingman hit six homers with a .557 slugging percentage. He was on the roster for the 1971 NL Playoffs, but went 1-for-9 as the Giants fell to Pittsburgh. It would be his only appearance in the postseason.

At his first big league training camp in 1972, Kingman was presented with a gift: a third baseman’s glove. With his strong arm, the team hoped he could quickly adapt to the hot corner. He was at that position for game two of the regular season against the Astros, when he hit for the cycle and drove in six runs. It seemed like Kingman was destined to do great things.

“Kingman can move in either direction, positions his feet well, and throws well,” said Giants coach Joe Amalfitano. “He has the agility, quickness, and real desire to learn. If I were a fan coming into the ballpark now … and saw Dave playing third, I’d probably say to myself ‘This guy has played the position before.’”

Reports of the Kingman experiment at third base were sure to point out that the Giants felt Kingman was one of their best athletes, and “faster than any Giant except Bobby Bonds.”

But baseball had never seen a third baseman that tall before, and when McCovey suffered a broken arm in the first week of the 1972 season, Kingman was waved over to the other side of the infield. When Mac returned in mid-June, the Giants benched the struggling Henderson, and Kingman grabbed a different glove to play left field. The juggling didn’t bother Big Dave at the plate: he clubbed 29 home runs and drove in 83 runs in his rookie season. He even got a smattering of support for the National League MVP Award.

“The main thing is to have Dave’s bat in the lineup,” Fox said.

As soon as a team becomes static, it loses ground, and the 1973 Giants were destined to experience change. Willie Mays was gone, and so was ace Gaylord Perry. The outfield logjam was cleared when Ken Henderson was traded. Foster had been traded away the year before, but that didn’t mean Kingman was guaranteed a spot. That’s because Bonds and young stars Garry Maddox and Gary Matthews were ensconced in the outfield. Mathews won the left field job in spring training, which meant Kingman was going to have to find playing time somewhere on the infield.

The 1973 season began with Kingman on the bench. He never really got consistent starting time until September, when he filled in for injured third baseman Ed Goodson. In 305 at-bats, he hit 24 home runs, the third-highest figure on the team. But he was a man without a position. Some in the Giants organization also felt Dave, who struck out 122 times (or 50% of his outs), was undisciplined.

How different was baseball in the 1970s? San Francisco hitting coach Hank Sauer had this to say about Kingman in 1973: “If Dave could reduce his strikeouts to 90, he could hit .300 and still get plenty of home runs.”

Sauer represented the prevailing wisdom of baseball at the time: batting average and contact mattered more than the long ball. Kingman’s 59 homers in his first 892 at-bats be damned, the Giants wanted fewer strikeouts.

The past was buried in the 1973 offseason, when the Giants traded McCovey to the Padres. The move cleared the way for Kingman to play the position best suited for him: first base. But the 1974 campaign would not be his coronation as Big Mac’s successor, instead it would prove to be his final year with the organization that drafted him.

Kingman got off to a good start in 1974, but by mid-summer, he was struggling to make contact. In July and August over a 24-game stretch, he struck out 26 times and batted .190 with five homers. Fox was fired and replaced by Wes Westrum in late June, and his arrival led to a new appraisal of Kingman.

“We have to get men on base and knock some singles,” Westrum explained a few weeks into the job. “I don’t want rally busters, I want rally starters.”

Apparently that meant Westrum wanted a lineup of leadoff hitters, but whatever he meant, it was not good news for Kingman. The slugger hit only eight home runs after August 1, and went 16 games without a four-bagger. He struck out 125 times in 350 at-bats. The Giants lost 90 games and finished in fifth place.

The Giants hated all those strikeouts, and in February of 1975 they jumped at the $150,000 the New York Mets offered for the 26-year old Kingman. His new team was thrilled at the prospect of 25 homers, 25 homers, maybe even 40+ homers from the tall slugger. But they also had to solve the same problem that plagued the Giants: where to play Big Dave?

New York sportswriter Jack Lang assessed Dave’s defense when he included this in a spring training column: “If you’ve ever seen a pelican take off, you have a small idea of what it’s like watching Kingman go after a fly ball.”

Kingman began his Mets career in right field, and on opening day at Shea Stadium he hit a home run off Steve Carlton that helped Tom Seaver to a victory. But Rusty Staub was bound to play right, so Kingman was swapped to left field in place of injured Cleon Jones a few days into the season. Still, his status as a starter was tenuous.

At the All-Star break in 1975, Kingman’s 15 home runs ranked third in the league, but manager Yogi Berra still hadn’t settled on a position for his slugger, or whether he wanted to play him every day. In May, when Berra benched Dave against right-handed pitchers, Kingman’s pride led him to revolt. He threatened to bunt every time he went to the plate against left-handed pitching. Later, when asked why he thought he wasn’t playing regularly by reporters, Kingman shrugged, and said, “I don’t know, you have to ask Yogi.” Diplomatic, he was not.

The same reporters asked Kingman how many homers he felt he could hit if he played every game. “I don’t know,’ Kingman snorted, “why don’t you ask me how many times I would strike out if I played regularly?”

Baseball was not ready for an all-or-nothing, big-swinging hitter in 1975. They were also not as patient back then with an athlete who spoke his mind. Both traits would cloud Kingman’s career.

Berra was fired after the Mets were outscored 14-0 in a doubleheader sweep in early August. By that time, Kingman was proving his little manager wrong: he hit 13 homers and batted .322 in July. Though he sagged to a .187 mark and 12 homers in his final two months, Kingman still produced 36 home runs, setting a franchise record.

Nothing compares to being famous in New York. Being a superstar in San Francisco or St. Louis is much different than being one in the Big Apple, for example. When Kingman swatted 73 homers in the 1975-1976 seasons for the Mets, fans anointed him “Sky King,” for the tremendous height of his blasts. He was called “King Kong” and had his face on magazine covers. The success on the diamond was welcome vindication for Dave, but the attention was uncomfortable. Kingman was never good at being the center of attention. Maybe it was because of his size. Since he was about 11 or 12 years old, Kingman had always been a tall, gangly, long-legged behemoth. That type of attention was awkward and unwanted. Being a superstar in New York for the Mets, Kingman strained under the spotlight.

“It’s just that I prefer a private life of my own,” Kingman said. “I like to live quietly.”

In 1976, Kingman hit a ball out of Wrigley Field that some observers estimated to have traveled 600 feet. It almost certainly didn’t, but it landed across the street outside the ballpark, probably 540-560 feet from home plate. He hit baseballs that far a few times every year during his prime. In his first spring camp with the Mets, Kingman hit a ball out of a ballpark in Fort Lauderdale. A former Yankee legend was in the stands when the baseball left the field. “That’s the longest home run I’ve ever seen,” Mickey Mantle said.

In 1976, Kingman was introduced to a man who finally understood him. “Joe Frazier is beautiful,” Kingman said of the new Mets manager. “The man told me the job was mine, and that I would play every day. That is all I ask.”

Kingman missed a few weeks with injuries in 1976, but he still hit 37 homers, breaking his own team record for a single season. For the second straight year, he finished second to Mike Schmidt in the home run race.

The 1977 season will go down as the worst in Mets history, but Kingman wasn’t the reason. He simply got churned up in the wake of tidal shifts for the team. The best player in franchise history, Tom Seaver, was facing free agency, and he wanted to remain in New York. But the owner, Donald Grant, was a boob, who decided to quibble over money with baseball’s greatest pitcher. At the trade deadline, Grant dealt Seaver to the Reds, ridding himself of a headache and pissing off Mets fans for a generation. The same night, he dumped Kingman on the Padres, choosing to get something in return for his slugger. Kong had indicated that he wanted a long-term contract in the neighborhood of $2.5 million. But Grant, like most owners back then, was tone-deaf to the economic changes in the sport.

Kingman’s odyssey in 1977 was just starting when he donned the uniform of the Padres on June 17. He should have known his situation was dubious. Manager Alvin Dark was unsure how to get playing time for his new slugger. He had young Mike Ivie at first base, rookie speedster Gene Richards in left, and another Big Dave (Winfield), in right.

“I wonder if we could get the National League to put in the designated hitter rule for us?” Dark said.

The Padres could have used Kingman. In 1976 the entire team hit 64 home runs. But the Kingman Problem would not plague Dark for long. In September, the team placed Kingman on waivers for purposes of exploring a trade. The Angels claimed the pending free agent, and Kong was on his way to the American League.

“You just got the pennant for 1978,” said Rod Dedeaux, Big Dave’s college coach. “Kingman can make the difference. He hasn’t scratched the surface of his potential yet. This guy can top Babe Ruth.”

“The next Babe Ruth” only stayed with the Angels for about a week-and-a-half, hitting two homers, before the Yankees gave up a mid-level pitching prospect for him. It was an insurance move: the Yanks were only a couple games ahead of the Red Sox and Orioles in the AL East. Manager Billy Martin wrote Kingman’s name in as his DH six times down the stretch. Back in New York, King Kong blasted four home runs. But he was left off the postseason roster. He was a free agent, and his 99 homers in 1975-1977 ranked third in MLB.

In his first seven seasons, Kingman treated Wrigley Field like his own batting cage. In only 44 games as a visiting player, King Kong was like a rampaging gorilla in the ballpark, hitting 18 home runs with 48 RBI and a .685 slugging percentage. In Chicago in the ballpark without lights, Kingman hit like Babe Ruth.

That’s why Bill Wrigley, the third generation in his family to own and operate the Cubs, agreed to spend lots of his gum money to lure Kingman to the team as a free agent. In February of 1978, with $1.2 million guaranteed to him over five years, King Kong reported to camp with the Cubs.

“In this park he can break records,” said Joe Amalfitano, the same guy who taught Kingman how to play third base with the Giants.

With Bill Buckner at first base, the Cubs inserted Kingman in left field. With all the money the team paid for him, the expectations for Kong were very high. When he got off to a slow start in 1978, the boo birds haunted him in left field at Wrigley. A hamstring injury kept him out of the lineup for a few weeks, but eventually his right-handed swing showed how small Wrigley Field was. He slugged .591 with 18 home runs and 53 RBI in 65 games in the ballpark. But that was just a preview of what would come in his second season as a Cub.

Kingman lofted a baseball onto Waveland Avenue on opening day in 1979. He hit three homers in his first seven games, and seven in his first 15. By May, city officials had replaced a WAVELAND AVE street sign outside Wrigley Field with one that said KINGMAN AVE.

The Cubs and their fans didn’t get upset about the strikeouts. King Kong had 48 K’s in his first 45 games in 1979, but his 15 homers and .584 SLG were all that people cared about. He was also hitting .283 and leading the league in RBI. June was even better: .329 with 12 HR and 29 RBI in 23 games. He had 29 home runs in 79 games at the break. For the second time, Dave was named an All-Star.

In a game at Wrigley in May, Kingman and his home run champion nemesis Mike Schmidt put on a show that will live in Chicago baseball history. That afternoon, Kingman belted three home runs against the Phillies, one of them landing on Waveland Avenue. A second traveled beyond Waveland and onto Kenmore Avenue, landing on the roof of the third house on that street. It was estimated to have traveled 554 feet. Schmidt did him one better, smashing four home runs in a wild, 10-inning, 23-22 victory over the Cubs.

Folks thought Kong might challenge the single-season home run record, but he cooled and finished with 48, the most by a Cubs batter since Hack Wilson hit 56 in 1930. Kingman finally snatched the home run crown from Schmidt, led the league in slugging and OPS, and finished 11th in MVP voting.

Quicker than you could say “Holy Cow,” the Cubs and their fans turned on Kingman. In 1980, he suffered a pair of injuries that kept him out of the lineup for two weeks in May, another week in June, and almost all of July. At the same time, he was writing a column for a Chicago newspaper. During his absence from the team, Kingman leveled criticism at the front office for not improving the roster. He also stopped talking to reporters. The fans bristled with every absence by King Kong from the lineup. A popular jumper sticker started to appear in the Windy City that read: “Hey! Hey! The Cubs Are On Their Way! Dave Ding Dong Went Fishing Today!” In August when he returned to the team, Kingman took offense at the scrutiny from the press, and dumped a bucket of ice water on a reporter in the clubhouse.

The Wrigley family was fed up with owning a baseball team that bled money. In September, general manager Bob Kennedy was ordered to dump salary. He was mandated to get Kingman out of a Cubs uniform. A deal wasn’t reached until the following February, when the Cubs sent Kingman to the Mets for outfielder Steve Henderson. “King Kong” was going back to New York.

Kingman did all he could to appear like a changed man as he started his second stint with the Mets. In spring camp, he poked fun at the ice water bucket incident.

“The publicity I got from that was unbelievable,” Kingman told nervous New York sportswriters. “I’ll admit I’m an agitator. I love practical jokes. But in a fun way, not in a vindictive way.”

Mets manager Joe Torre was happy to welcome Kingman. “Just having Dave in the number four spot is bound to help [Lee] Mazzilli,” Torre said. “He led the club in walks last year because they pitched him carefully. They won’t be able to [walk Mazzilli] this year with Kingman behind him.”

Torre was the perfect manager for Kingman, and the tall slugger, who was 32 years old in 1981, had one of his best and most controversy-free seasons. In May, Kong set a team record by driving in at least one run in seven straight games. He even agreed to meet with reporters after prodding by Torre. In a strike-shortened season, Kingman missed only five games, hit 22 homers, and led the Mets in RBI and walks.

In 1982, Torre was gone, but Kingman stayed healthy and avoided trouble. He tied his Mets franchise record with 37 big flies, winning his second home run title. Still, many observers chose to focus on his league-high 156 strikeouts and a .204 batting average, the lowest by a home run champion in baseball history.

The Mets acquired Keith Hernandez at the June trade deadline in 1983, which meant Kingman’s days were numbered at first base. Kong managed only 13 homers in an injury-plagued season. Under interim manager Frank Howard, he was platooned against left-handed pitching. That offseason, after his one-year contract with the Mets expired, the 35-year old was released.

From 1981 to 1983, Kingman batted .208 and was second in baseball in strikeouts per 100 at-bats. His OPS was 102, and he averaged 24 HR per season, but in the early 1980s, if you struck out too much, couldn’t play in the field, and had a low batting average, most teams treated you like a leper.

The Oakland A’s were not most teams. In 1984, the A’s were basically what they are in the 21st century: a small market team with an owner who is allergic to expensive contracts. The front office was led by Roy Eisenhardt, a lawyer who was married to the daughter of the team owner. If there’s anything more subservient than a son-in-law working for his father-in-law, we don’t know what it is. Eisenhardt had to be a bargain shopper, so he offered Kingman a $250,000 contract to be a designated hitter.

The DH was made for Dave Kingman. With Oakland for his first extended stretch in the AL, Big Dave tucked himself into his locker, kept quiet, and took his four of five turns at the plate every night. In his ninth game in the bright green and gold of the A’s, Kingman hit three home runs against the Mariners at the Kingdome. In that game, he drove in eight runs. A week later he smashed three homers in two games against Boston at Fenway Park. In April, the tall, quiet power hitter had 10 home runs and 26 RBI in 21 games.

Kingman hit .268 with 35 home runs and 118 RBI in 1984. He was named the American League’s Comeback Player of the Year, and finished 13th in MVP balloting. It was a resurrection that amazed baseball experts, and frustrated his former teams, most of which had given up on him.

In 1985, Kingman set a career high in games played and plate appearances. He might be the only 36-year old to ever do that. In early August in Seattle, he hit his 400th career home run. At the time he was one of only 21 batters to reach that milestone, and only the eighth right-handed batter to do so.

For many in the game, Kingman’s accomplishment only served to underscore what he wasn’t good at. When a reported profiled Oakland prospect José Canseco, the young ballplayer bristled at comparisons to Kingman. The article ended on an emphasis that Canseco was a multi-talented ballplayer with a good arm and defensive ability. “No Kingman clone,” it said.

On the heels of his milestone, Dave Kingman’s name found its way to another noted slugger. Reggie Jackson was asked the chances of him going into the Baseball Hall of Fame with Kingman. “You can say I won’t make the Hall of Fame,” Reggie said. “You can say I stink. But don’t put me in the same story with that guy.”

“That guy” hit only four fewer home runs in the 1980s than Jackson did (194 to 190), but respect was not attached to those slugging numbers. Kingman had burned bridges, was aloof, and his extensive travels had never helped any of his teams reach the World Series. Still, the stinging comment from Reggie, who smashed the all-time record for strikeouts, seemed like piling on.

Kingman was realistic about his legacy, even after admitting he would like to get to 500 home runs. “I’m a lifetime .240 hitter, and how many of them are in the Hall of Fame?” he asked.

Despite 30 homers for a second consecutive year in 1985, Kingman accepted a 25% pay decrease to come back as DH for the A’s in 1986. He was still earning more than $700,000, which some sportswriters felt was absurd for a man hitting in the low .200s with oodles of whiffs.

“I’ve had critics all my career,” Kingman said in a rare interview. “When those stories came out, I had a good laugh.”

Once again in 1986, Kong got himself into a confrontation with a reporter. Kingman sent a live rat in a pink box to Sue Fornoff, a sportswriter for The Sacramento Bee. The rat had a tag attached to it that read, “MY NAME IS SUE.” Fornoff claimed that Kingman had told her that women do not belong in the clubhouse, and that he harassed her several times since she began covering the team. Kingman himself said it was intended as a harmless practical joke. The A’s were not amused, fined Dave, and warned that they would void his contract if something like it happened again. The final weeks of his 1986 season were spent with Kingman tip-toeing around a clubhouse that seemed fed up with him. At the end of the year, Oakland let him leave as a free agent, but no teams offered a contract, even though Kong had swatted 35 homers and drove in 94 runs.

In February 1987, Kingman drove himself to spring training sites in Arizona and Florida, offering his still-powerful bat to any team willing to pay him even league minimum. From 1984-1986, Kong’s 100 home runs ranked third in baseball, and first in the AL. But Kingman didn’t receive an offer. In July, his original team the Giants gave him a minor league deal. The 38-year old returned to Phoenix 16 years after his last appearance at Triple-A, hitting two home runs in 20 games. Without a path back to the big leagues, Kingman retired.

In 1990, an arbitrator ruled that MLB owners had colluded to keep free agents like Kingman from being offered a contract in the 1986 offseason. Kingman was awarded more than $800,000 in damages, a slight victory against a game that cast him aside.

Kingman played 16 seasons and appeared in nearly 2,000 games. It’s difficult to classify that as a disappointing career, but many have tried. He was a tall, muscular, strong-armed former pitcher with a long, uppercut home run swing. He was supposed to rewrite the record book. But, that never happened. Most of it wasn’t his fault: baseball is hard. But, Sky King didn’t help his case by being distant and rude to teammates, and aggressive with reporters. There were other batters who played in his era who also had troubles with strikeouts (Mike Schmidt famously battled boo birds in the first few years of his career), but King Kong Kingman became the most vilified all-or-nothing slugger of his time. He was criticized when he asked for big money, criticized when he pestered his manager for playing time, and criticized when he slumped. All players have slumps, some worse than others, But Kingman’s bad stretches invited the bad words that writers can spill onto their pages. He was never seen as a winner, but more like a freakish oaf who was lucky to have one skill. That’s why teams traded him so often. That’s why many fans disregarded him once the home run binges disappeared.

Big Dave deserved a better fate. He wasn’t the only moody, sexist athlete in America. He wasn’t the only baseball player who swung for the fences at the expense of all else. He was just the ugliest, and he was punished for it by the game that he chose as a career.