Now known as the Guardians, the Cleveland Indians were a charter member of the American League.

The franchise has been at the center of several innovations in baseball, including the first ballpark lights in the AL, first radio broadcast, and for fielding the first black player, Larry Doby in 1947.

This new list ranks the 20 greatest players in Cleveland franchise history based on their years with that team only, according to Wins Above Replacement (from Baseball-Reference.com).

This list is not an opinionated ranking of the best players to have played for Cleveland. It’s based on bWAR. Why do we use bWAR? Because it makes it easy to put the lists together. The real reason I write these articles is to comment on these players.

This is one in a series of articles on the 20 Greatest Players for Each MLB Franchise.

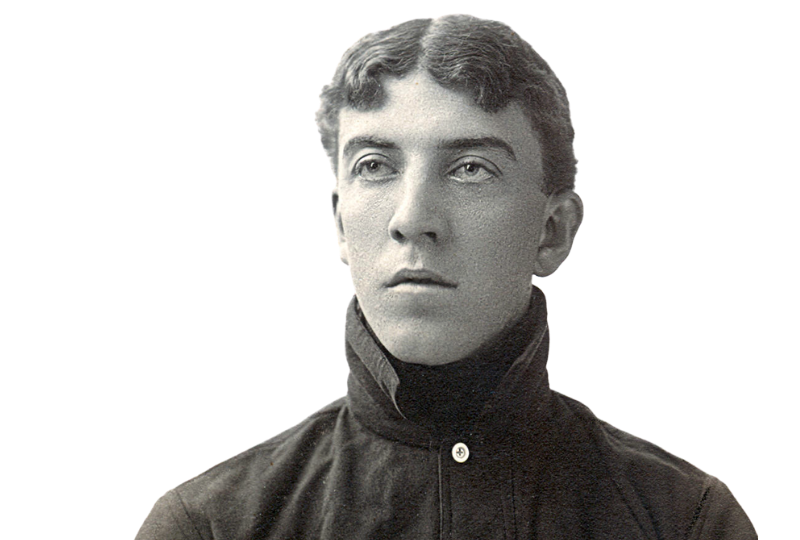

Jackson is best known for his dastardly deed of helping to throw the World Series as a member of the White Sox. But he hit an amazing .375 in six seasons as an Indian. In 1911, with Cleveland, Shoeless Joe batted .408, but didn’t even win the batting title.

Cleveland traded Jackson in the middle of the 1915 for several reasons. For one, Joe was threatening to retire and become a stage actor. For another, the team had moved him to first base to make room for another outfielder. And most importantly, the Cleveland owner, Charles Somers, didn’t want to pay Jackson when his contract expired. He was shipped to Chicago, and became a criminal a few years later.

Ferrell was the best hitting pitcher of his era and possibly of all-time. He hit 38 career home runs, ten more than his Hall of Fame brother and catcher Rick. In 1935 with the Red Sox, Wes hit a walk-off home run in consecutive games, first as a pinch-hitter and then in a game he pitched.

“I didn’t see any big deal in being a good hitter as well as a good pitcher,” Ferrell said. After his major league career ended, he played outfield in the minor leagues for years, winning multiple batting titles.

Uhle most likely discovered or invented a new pitch in the mid-1920s, which he called a slider. But he apparently held the baseball in a different manner than later practitioners of the pitch.

“It just came to me all of a sudden, letting the ball go along my index finger and using my ring finger and pinky to give it just a little bit of a twist,” Uhle said. “It was a sailing fastball, and that’s how come I named it the slider. The real slider is a sailing fastball. Now they call everything a slider, including a nickel curve.”

Turner is the only position player to spend as many as 15 consecutive seasons as a member of the Cleveland team. He was a good defensive shortstop, but offensively similar to Omar Vizquel.

Turner was called “Cotton Top,” because he had very light, white blonde hair.

“That space between the white lines, that’s my office, that’s where I conduct my business.” — Early Wynn

“If you hit a line drive up the middle against Wynn, he would throw over to first base, but he wasn’t trying to pick you off. He would throw the ball at you.” — Al Kaline

Probably threw his fastball as hard as Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson. But for many years, Sam didn’t know where the baseball was going to end up.

Still, from 1965 to 1970, McDowell led the AL in strikeouts five of six seasons, and had a 128 OPS+. He topped 300 K’s twice, but his arm died on him before he was 31.

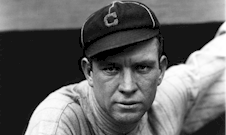

He was a lot like Dale Murphy as a player, but an even better hitter. Doby was a good base stealer too, but the Indians under Al Lopez didn’t like to steal, in fact no one really liked to steal bases in the 1950s. For the first few years of the 1950s, Doby was the best player in the American League, before Ted Williams got rolling again and Mickey Mantle emerged. He had tremendous power, was solid in center field, and he did everything you wanted offensively: he hit for average, hit some doubles, homers, and drew bases on balls. He deserved to win the MVP in 1952, but they always gave it to a Yankee as long as they were winning pennants.

We have Doby ranked 27th among center fielders all-time, but he could rate higher, we simply can’t know how great he was in the negro leagues.

He’s already hammered 200 homers through the All-Star break of his age-30 season. If Ramírez averages 33 home runs per season in his age 31-38 seasons, he’ll reach 500. Given the way home runs are flying out of parks, with the emphasis on launch angle and a “go-for-it” offense, it’s very possible.

Harder was in the Cleveland rotation from 1930 through the World War II years. He was for a few years among the best pitchers in the league, but typically he was a solid, innings-eater, and a crafty moundsman.

He won 223 games, all of them with the Indians. He was the only pitcher to win at least 15 games each season from 1932 to 1939. Harder went on to be an important pitching coach, again for Cleveland, helping them to a pennant, and overseeing 11 different 20-game winners.

Joss won 27 games for Cleveland in 1907, when he was clearly the most effective pitcher in the league. He went 160-97 in nine seasons, all with Cleveland, and even tossed a perfect game.

Joss died from tuberculosis at the age of 31 early in the 1911 season.

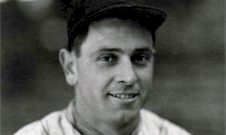

Sewell started by hitting .329 down the stretch for Cleveland during the 1920 pennant race. He was a line-drive hitter, a great fastball hitter, and he could do just about anything with a baseball bat. One season he had 22 bunt hits, and another year he had 41 sacrifice hits. He was the hardest batter to strike out in history, he struck out a total of 41 times in his last nine seasons. He was also a plus defender and he had a strong arm, so strong that he played third base for a few years.

You all know him. You know what he did for a living.

“I have to rate Lemon as one of the very best pitchers I ever faced. His ball was always moving, hard, sinking, fast-breaking. You could never really uhmmmph with Lemon.” — Ted Williams

We have an in-depth look at the remarkable career of Lemon, who was a fantastic pitcher, and later a great manager.

If they never put this guy in the Hall of Fame, the voters should be ashamed of themselves. He was a great performer, and ranks among the ten best baserunners and stealers in the history of the game.

From 1992 to 1996, Lofton stole 325 bases and struck out only 324 times. Hard to do in the Steroid Era of arm-bashing and home runs.

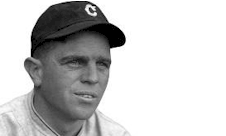

Let’s go through all the nicknames Averill acquired, he had several. He was “The Earl of Snohomish.” because he hailed from Snohomish, Washington. They called him “Popeye” after the comic strip character that became popular in 1929, the same year Averill debuted with the Indians. Averill was 5’9 (about average for an American male in the 1930s) but (like Popeye) he had prominent forearms and he was very strong. He was opinionated and stubborn, which is why teammates dubbed him “Rockhead” or simply “Rock.” When Cleveland purchased his contract from the San Francisco Seals, Averill insisted that he get a portion of the money. He battled the Indians over his salary almost every year of his career. “The way I look at it,” Averill once said, “a player ought to get all the money he can.” Roommate Lew Fonseca noted that Averill never made his bed and often wore wrinkled suits on road trips, prompting the nickname “Sloppy.” Find a photo of Earl Averill and you’ll see why his teammates playfully called him “Elephant Ears.”

When people discuss the greatest performances in World Series history they usually forget about Stan Coveleskie’s pitching in the 1920 World Series. The spitballer started Game One, Game Four, and Game Seven (it was a best-of-nine back then). He allowed a total of two earned runs in his three starts, walked only two batters, and won all three games. He pitched Game Four on three days’ rest, and Game Seven on two days’ rest. With grief still on his mind, Coveleskie pitched brilliantly to lead the Indians to their first World Series title.

He may have had the most important single season by any player in baseball history. Boudreau was, like Tris Speaker, a great player and a good manager, who guided Cleveland to a pennant as a player/manager.

When famed scout Cy Slapnicka found Bob Feller in Van Meter, Iowa, he returned to Cleveland and told the front office, “Gentlemen, I’ve found the greatest young pitcher I ever saw. I suppose this sounds like the same old stuff to you, but I want you to believe me: this boy that I found will be the greatest pitcher the world has ever known.”

Feller was the real deal, he was a great pitcher when he was 17 years old, and at that age he made his first major league start and struck out 15 batters. He was still a high school student and returned to Iowa after the season to finish his senior year. Feller was so famous by then that his high school graduation was broadcast nationwide on the radio. He struck out a batter an inning when he was 18 years old, and the following season in his final start of the year, he struck out 18 batters in a game against the Tigers. He threw the fastest fastball since Lefty Grove in his heyday, since Walter Johnson roamed the mound.

Tris Speaker has the best defensive statistics of any outfielder in history. He led the league in putouts seven times, in double plays ten times, and in assists by a center fielder eight times. Which is to say he caught more balls and made more great plays than any outfielder ever did.

“Spoke” played extremely shallow, almost like a “rover” in short center field, shifting to either side of second base depending on the batter. Dozens of times in his career, Speaker served as the pivot man on double plays in the infield. He was sort of a one-man defensive shift. He also made far fewer errors than outfielders of his era, and he could go back to catch a flyball as well as anyone.

I would suspect Lajoie’s place at the top of this list may surprise many baseball watchers.

Lajoie played his last game of pro ball in 1916, his last one in a Cleveland uniform in 1914. He was so talented, so popular, that the team was called the “Naps” in his honor.

Lajoie had a way of gliding toward the ball, like Cal Ripken Jr. did. He was a tall man but graceful, with a strong arm. He had some peculiar habits in the field: he liked to take his glove with him to the dugout between innings, shunning the practice of tossing the glove into short right field; and he liked to use a new glove each summer, breaking it in by coating it with whale oil and twisting and bending the leather until it was soft and pliable; he also removed the wrist strap so he could keep the glove low on his wrist, giving him more reach. It worked: Lajoie was a solid defender up the middle.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.

No posts found!