Here we are with the 20 greatest Giants (be they San Francisco Giants or New York Giants) of all-time. These lists are based on Wins Above Replacement. We invite you to leave a comment below.

The most important players in Giants’ postseason history:

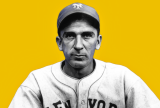

Frisch was at his best in the postseason. He was a key player in eight World Series, helping the New York Giants to a pair of championships. In the 1922 Fall Classic against the Yankees he batted .471 with eight hits in five games. The next fall he punished Yankee pitching again to the tune of .400 (10-for-25) in six games.

How good was he? Frisch was traded for Rogers Hornsby.

When he arrived as a young player with the Giants in the late 1960s, the team compared Bobby to Willie Mays. That was unfair, of course, and Bobby suffered for years under the weight of that comparison. Willie was a once-in-a-lifetime center fielder, and no matter what Bobby did with the glove, he would fall short. Willie had awesome power, but Bobby struck out a lot. Willie won home run titles and MVP awards, while Bonds did the 30/30 thing, which wasn’t nearly as exciting. When the media kept writing about his potential, Bobby took it as an attack. He didn’t like criticism, and he withdrew, bitter. That bitterness was manifested in his son Barry, who never trusted the fourth estate.

In the late 19th century, when professional baseball was teaming with rough players with ill manners, Tiernan stood out as a gentleman. He was so polite and so quiet that he was nicknamed “Silent Mike.”

A hard-hitting right fielder, Tiernan led the league in homers twice, and in runs and slugging once. He had a strong throwing arm (he started his pro career as a pitcher).

He invested his money wisely and retired at the age of 32 to open a saloon on 8th Avenue in Manhattan. Sadly, he died at the age of 51 in 1918 from tuberculosis.

The best “old” shortstops were Honus Wagner, Ozzie Smith, George Davis, Pee Wee Reese, Bobby Wallace, Barry Larkin, and Art Fletcher. That’s based on value from age 31 to 37. Fletcher didn’t get a starting job until he was 27 because he was stuck behind Al Bridwell, another very good defensive shortstop. John McGraw had the prescience to realize that Fletcher was a star and for several years he was the best all-around shortstop in the National League, in the stretch between the Giants two dynasties. Originally, McGraw harped on Fletcher because he refused to field grounders “on the run,” the preferred Giant method. Instead, Fletch insisted on getting his body in front of the ball, even if it took more time.

Fletcher was a chip off the old block for McGraw: fiery and obnoxious. Fletcher got in more fights than anyone in the league. Once, when he got tangled up with Rogers Hornsby in the middle of the diamond, the “Rajah” felled Fletcher with one punch to the jaw. Fletcher spiked more runners than Ty Cobb ever did, and he liked to brag about the exactness of his fists. He was loved by the fans at the Polo Grounds, especially by a woman who wore a large hat and frequently sat in the center field bleachers. When Fletcher took his position for the top of the first inning, the woman would galvanize her lungs and scream “Come on, Artie!” Fletcher would wave to her and the crowd would go wild.

Fletcher’s range factors are nearly off the charts, and he was probably better with the glove than Dave Bancroft, the Hall of Fame shortstop who came along about that same time, and for whom an aging Fletcher was traded during the 1920 season.

Once early in Fletcher’s career, when the Giants were visiting St. Louis, officials in Collinsville (Fletcher’s hometown, which was only 15 miles across the river in Illinois) organized a special day for him. But McGraw had Art on the bench when the game started, even though Fletcher’s parents were in the stands. Teammate Larry Doyle decided to do something about the injustice, getting himself thrown out in the first inning so Fletcher would have to play second base. Before that game, the Fletcher admirers gave the young infielder a diamond pin, which Art made into a ring and presented to his fiancé. She wore it for decades.

Fletcher managed the undermanned Phillies after his playing career and improved them by 18 wins in two seasons. But the roster was woeful and Fletcher quit after four years on the bench. The Yankees hired him as a coach in 1927, and when Miller Huggins died in-season, Artie handled the managerial duties for a few weeks. He spent nearly two decades on the Yankee staff as third base coach, waving in Gehrig, DiMaggio, and the others as the team won nine titles. Yankee players called him “Chisel Chin” because of his big jaw. In all. Fletcher earned more than $55,000 in World Series money as a coach, more than he earned as a player. Fletcher refused managerial jobs from several big league teams, preferring to avoid the anxiety of the job. He died in 1950 from a heart attack, five years after sending his last Yankee homeward bound.

Among second basemen since 1900 who played at least 1,300 games, Doyle’s 125+ OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging adjusted to era and ballparks) ranks ninth. It rates ahead of Hall of Famers Charlie Gehringer, Tony Lazzeri, and Joe Gordon. It ranks ahead of Chase Utley, Jeff Kent, and Lou Whitaker. It’s well ahead of Ryne Sandberg and Craig Biggio. Clearly, Doyle was a valuable offensive player. But how good was he?

At the height of his career, John McGraw said of Doyle, “I would not trade him for any man playing baseball.” Doyle won a batting title, he stole more than 30 bases in five straight seasons, he retired as the all-time leader for second basemen in hits, runs, extra-base hits, total bases, and RBIs. Also in double plays and total chances, though his defense (according to research by author Michael Humphreys) was dismal.

Doyle was important to several great teams, starring for the Giants when they won three consecutive pennants from 1911 to 1913, though they pulled a Buffalo Bills move and lost the World Series each year.

In 1912, Doyle was named Most Valuable Player of the National League. “Laughing Larry,” the guy who spent years as Christy Mathewson’s roommate, was an excellent player, although one-dimensional, 90 percent of his value coming with the bat. He had a sad stretch after his playing career, spending more than a decade in a sanitarium while suffering from tuberculosis. Doyle ended up being the last patient released after a treatment was found, and the press covered his final day in the institution. He lived another 21 years.

Jackson entered the National League as a very quick runner and with a strong throwing arm. He was skinny and when he first reported to the New York Giants he was initially assumed to be a bat boy. He pinch-hit as a 19-year old in the 1923 World Series. In his second full season, when he was 21, he tore cartilage in his right knee while rounding first base and his speed diminished. He played with that bum knee until 1932 when he chipped the bone in his left knee and underwent surgery. While Jackson was under the knife, the surgeon removed junk from both knees, but he was pretty slow after that, and shifted to third base. By all accounts, he maintained that rifle arm his entire career.

Injuries always hounded Jackson, and he only had eight seasons where he played as many as 120 games. In the minor leagues he suffered a fractured skull when he collided with an opposing player, a collision that left the other player blind in one eye. Jackson underwent an appendectomy in 1927, had the mumps three years later, and a bad case of the flu two years after that. In the case of each of those diseases, Jackson was seriously ill.

In spite of his ailments and craggy knees, Jackson still managed to receive MVP votes in seven seasons. That despite never having a great year with the bat. He usually batted sixth or seventh in the order, he had some decent years where he batted over .320 with some triples and homers, but everyone was hitting .300 in that era. He wasn’t fast, he didn’t steal bases, and he didn’t produce a lot of extra-base hits. He was just another bat in the bottom of the order on the Giants. If you do a search for his name in The Sporting News archives, not much comes up. No big feature stories, not much news, other than his injuries. He appeared in four World Series but didn’t perform well.

So why the love from baseball writers in the annual MVP voting? It has to be his defense. He wasn’t called “Stonewall” for the historical reference, he was, by reputation, a tough defender at shortstop. He was a starting shortstop for ten years, from 1923 to 1932, during which time his teams won two pennants (they added a third in 1933 and a fourth in 1936 when he played the hot corner). For that decade, according to Bill James’ Win Shares method, Jackson was the best defensive shortstop in his league.

With three World Series titles and several years to add to his crowded award shelf, Posey has a chance to finish his career ranked in the top ten at his position. Among catchers, only Johnny Bench, Thurman Munson, and Posey have won both a Rookie of the Year and an MVP award.

How well respected was Davis for his baseball IQ? At the age of 24, the Giants made him their player-manager. He held that position for less than a full year, but he continued to improve his play with every passing season as he developed into the greatest shortstop in baseball in the 1890s.

Female fans in New York loved Davis, dubbing him “Gorgeous George.” He was one of the game’s highest-paid players in his prime, and he cavorted with many ladies while he lived in the city. Later, Davis opened a popular restaurant near the current site of Central Park. In the offseason he enjoyed serving as host, welcoming politicians and wealthy citizens to dine at his establishment.

An Irish-Catholic from Brooklyn, Welch was small even for his era, but he had a strong arm. He pitched in the time when teams usually used two or three pitchers, which is why “Smiling Mickey” won as many as 44 games in a season and 307 for his career. He’s probably one of the most unknown Hall of Fame pitchers, but he was an important player in 19th century baseball, helping the Giants to titles in 1888 and 1889, when he won 53 games.

iant he was: Connor was 6’3 and about 220 pounds when he stepped off a train to play for the Troy Trojans in 1880. With his broad shoulders, square jaw, and long arms, he looked like a monster compared to his normal-sized teammates. But he was far from a monster: Connor had a quiet, gentle nature, and he was a good teammate. He was so well respected that he was only once tossed from a game by an umpire, and when that happened, the umpire apologized to Roger the next day.

In 1881, Connor hit the first grand slam in major league history, and it couldn’t have been more dramatic. He hit the blast with two outs and his team behind by three runs in the bottom of the ninth. It was the first of many historic achievements by Connor on a baseball field.

In 1886, playing for the Giants, Connor hit a baseball over the wall in deep right field at the original Polo Grounds and over the stands, onto 112th Street in Manhattan. The park was always a very difficult place to hit home runs, and the blast was notable in the 19th century when few players had the strength to belt a ball out of the playing field, let alone down the street.

Terry had a fierce competitive streak and approached the pennant race as if it was life or death. He led the Giants to a championship in his first full season, hit .354 as a player-manager, and led the team to two additional pennants. He could have continued to play, but retired at the age of 37 to concentrate on managing. Terry took losses very hard. After his team lost a game, he would sit in his office alone, in full uniform. An hour would go by and his players would be allowed to leave, but Terry would sit alone and ponder the loss, often remaining at the ballpark for hours.

He was the first player whose relationship with the media negatively impacted his Hall of Fame chances. Terry frequently banned reporters from his office or refused to give interviews. The baseball writers pondered his name on 14 ballots before they elected Terry, 18 years after his last game as a player. When the phone call came to inform him of his election, Terry coldly told a reporter, “I have nothing to say.”

“If we made contact against Marichal, we counted that as a hit.” — Pat Corrales

Juan Marichal had five different pitches and he would throw them at any time. When he pitched in Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Marichal would wait until the wind was gusting to deliver his pitch. The batter would see his high leg kick and have to pick up the baseball with the Pacific wind blowing in his face.

Marichal was sort of the dragon slayer. Against the five premier pitchers in the National League (Warren Spahn, Bob Gibson, Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Jim Bunning), the Dominican Dandy was the best in head-to-head competition. In 43 starts against that group, Marichal was 24-12 with a 2.11 ERA. In 1966 he tossed a 14-inning shutout to defeat Bunning and the Phillies, but his most famous performance came against Spahn in 1963. In an epic battle between the 42-year old Spahn and the 25-year old Marichal, the two aces put up zero after zero, inning after inning. Finally, after he pitched 16 shutout innings, Marichal’s teammates scratched a run across against Spahn in the bottom of the 16th. In the years they were at their peak powers, Marichal and Koufax did not face each other much. The Dodgers preferred to use Johnny Podres, and later Drysdale against Marichal, and Juan won the head-to-head series against Double-D, 10-3, with three no decisions.

In spite of his success against the other legendary pitchers of his era, Marichal never won a Cy Young Award. “If Marichal had pitched in any other era,” Ron Fairly said, “they would be talking about him the way we talk about Koufax, Gibson, and Drysdale.”

“The Hoosier Thunderbolt” led the league in strikeouts five times, and won 20 or more games eight times. Though he did throw hard, he did not have good control of his pitches, leading the league in walks five times and being seventh all-time among the career pitching leaders in that category. In 1890 he walked 289, the all-time single-season record.

In 1897, one of his fastballs struck future Hall of Famer Hughie Jennings in the head, rendering him comatose for four days before recovery. Rusie’s wildness had been a catalyst for officials to change the distance from the pitching rubber to home plate from 50 feet (15 m) to the current 60 feet 6 inches (18.44 m).

Ott hit 63 percent of his home runs at the Polo Grounds. The right field foul pole was 257 feet from home plate, which was very convenient for a pull-hitter. His odd batting stance was designed to allow him to pull inside pitches. He stood with his lead (right) leg pointing to first base so his stance was open. When a pitch was delivered Ott lifted the lead leg as a weight shift device, like Darryl Strawberry did, or more aptly, like Sadaharu Oh, who was built a lot like Master Melvin. Many of the Japanese hitters use the leg kick timing mechanism, you saw it with Oh and other great Japanese sluggers. The reason for it traces back to the history of baseball in Japan. The man who introduced organized baseball to Japan, the man who taught them the American Pastime, was “The Man in the Green Suit,” Lefty O’Doul, who also happened to be one of the best batting coaches in history. O’Doul was on the Giants when 19-year old Ott won the right field job. O’Doul tutored Ott, he tutored an entire nation, and that’s partly why, decades later, Ichiro hit the way he did.

Willie probably could have won the Most Valuable Player Award eight or nine times, but baseball writers liked to throw the honor around and hand it to someone on a pennant-winning team most years. As it was, Mays won the MVP twice, and was runner-up twice and third in voting twice. He was named to the All-Star team 24 times.

How good was Willie Mays? Only six players have ever led the league in home runs and stolen bases at some point in their career. Mays did both four times each.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.