Harold Baines was on the Hall of Fame ballot for five years, never receiving as many as 50 votes. When he dipped below five percent in 2011, he fell off the ballot. Clearly, not enough baseball writers felt he was worthy. But what if his career had unfolded a little differently?

Twice in his 22-year career, Baines was robbed of games due to labor stoppages. In 1981 and again in 1994-95, the owners and players came to loggerheads and shut down the game.

Could those two labor disputes have caused Baines the hits he needed to get to 3,000?

If Baines has 3,000 hits on his ledger when he debuts on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2007, does he garner enough support to be elected?

It would be hard for the voters to ignore a player with 3,000 hits. Entering 2019 there have been 31 players who have reached the 3,000-hit mark, and all but six of them are in the Hall of Fame. Pete Rose, who was ruled ineligible for the HOF due to his lifetime suspension from Major League Baseball for gambling, is one of them. Another is Rafael Palmeiro, who tarnished his image by lying about his use of performance-enhancing drugs. The other four are Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez, Ichiro Suzuki, and Adrian Beltre, none of whom are eligible yet.

Baines finished with 2,866 hits, putting him 46th on the all-time list, behind the 31 members of the 3,000-hit club and 14 others. Those 14 got somewhere between 2,873 (Babe Ruth) and 2,987 hits (Wahoo Sam Crawford). Both of those players are in the Hall of Fame, and so are 11 of the other 12 who sit just below 3,000 hits. Only Barry Bonds (2,935 hits) is not yet in the Hall, though his candidacy is gaining steam.

The next seven players below Baines on the hits list are all in the Hall of Fame. Most of the players who collected at least 2,700 hits are in the Hall (52 of the 62 players eligible). To be fair, many of those players are in the Hall for other reasons. The hit total is often a by-product of a long, successful career. Maybe they hit for tremendous power like Lou Gehrig. Or they were run producers like Tony Perez and Billy Williams. Or perhaps they did a lot of things very well, like Ken Griffey Jr. and Rogers Hornsby. Or they were amazing defensive players who could hit too, like Charlie Gehringer and Brooks Robinson.

Baines is not a Tier I Hall of Famer. He’s not Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson or Stan Musial, to select three corner outfielders. He’s also not a Tier II guy, a guy who did one thing exceptionally well or did a lot of things really well (think Lou Brock and Robin Yount). Baines, if he were to be a serious candidate, would fall in Tier III, where you find Jim Rice and George Kell. The Hall of Fame is not filled with Tier I and Tier II guys, most of the members are in Tier III. This group includes the compilers (Sam Rice, Orlando Cepeda, Don Sutton) and the peak performers (Rube Waddell, Ralph Kiner, Kirby Puckett).

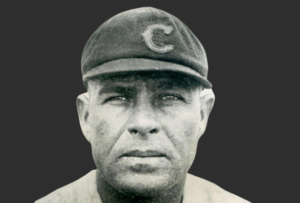

In 1981, Baines was in his second season in the majors. The previous year at the age of 21 he was a much-ballyhooed rookie, having been scouted personally by White Sox owner Bill Veeck. Baines played in 141 games as a rookie right fielder. He had a “perfect swing,” a left-handed stroke so beautiful it was compared to that of Ted Williams. He looked like a future star.

Baines started the ’81 season slowly: on May 1st he was hitting below .200 and had fallen to seventh in the Sox lineup. His bat heated up as the weather warmed but in mid-June the season was halted by the players’ strike. The game was put on hold for two months. Baines and the White Sox lost 56 games on the schedule. Given his pace that season, that probably cost Harold 50 hits.

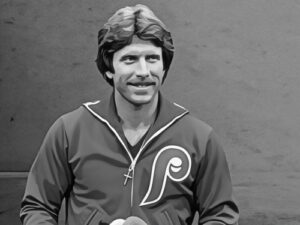

Fast forward to 1994 and Baines is a 35-year old designated hitter for the Orioles. On August 11th the players walked out and never came back. Baines had been having a good season, hitting nearly .300 with 16 home runs. Baltimore’s Camden Yards was a perfect fit for his swing. In three stints with the O’s, Baines hit .312 with a .520 slugging percentage in Camden Yards. The reason Baltimore kept reacquiring the veteran slugger was because he could rake in their park. But his ’94 season was aborted.

Baines missed 50 games in 1994, or another 50 hits. Add those 50 to the 50 from 1981 and you get Baines to 2,966 hits for his career.

But that’s not all — in 1995 the season was still in jeopardy when the owners and players were still at odds. The owners threatened to employ replacement players, the fans were the victims of the crisis. The labor issues dragged into spring training before finally being settled, but it caused the leagues to trim the schedule by 18 games per team.

Harold had a good season in ’95, he hit .299 with 24 home runs in 127 games. Give him his same production for the missing 18 games, and that adds 16 hits to his ledger. So, let’s check the numbers:

1981: 56 games missed, add 50 hits

1994: 50 games missed, add 50 hits

1995: 18 games missed, add 16 hits

TOTAL: 124 games missed, add 116 hits

Add the 116 hits to Baines’ 2,866 career hits and we have 2,982.

If Baines has 2,982 hits, how likely is it that the White Sox allow him to stick around for a few more months to get to 3,000 in 2001 when he was a 42-year old designated hitter? The Sox have a history of helping veteran players create milestones. They nudged Early Wynn toward 300 wins, and they signed Tom Seaver and Steve Carlton late in their careers.

It’s fair to assume that if Baines entered 2001 less than 20 hits away from the magical 3,000 plateau, the Sox would have found a way to get him there. This is the same franchise that put Minnie Minoso in uniform in 1976 when he was 50 and again four years later in 1980 when he was 54, just to get him the title of “oldest man to get a base hit in the big leagues.” The White Sox even noodled the idea of letting a 64-year old Minoso play in 1990. Playing an over-the-hill Baines at 42 to get his 3,000th hit in front of the hometown fans wouldn’t have been the sideshow that the Minoso affair had been.

But in the real world, Baines was 145 hits away from 3,000 when he started the 2001 season. He played for two months, performed poorly, and was dropped from the roster in June. He was asked back for a “tip of the cap” appearance in September. And that was it — his career was over.

Had the labor stoppages never happened, would Harold Baines have reached 3,000 hits? I’d say it’s better than 50/50 that he would have.

If Harold Baines has 3,000 hits the baseball writers would have been forced to think about him much differently. Combined with his other credentials: the more than 900 extra-base hits, the more than 1,600 RBIs, the .289 career average, it would be hard to ignore him.

Of course, they also would have looked at his more than 1,600 games as a designated hitter (almost 60 percent of his playing time). Had that happened, we might think about 3,000 hits differently. We might view Harold Baines much different too.