UPDATE: In 2021, the Golden Days Era committee elected four former players to the Baseball Hall of Fame. That election has prompted me to update this list, which was originally published in 2018.

Let’s look at the nine worst players in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

9. Herb Pennock

The Red Sox traded Herb Pennock to the Yankees before the 1923 season and didn’t think too much about it, because Pennock was a skinny lefty who had trouble with his command and walked nearly as many batters as he struck out. His career record to that point was 77-72, and Pennock’s ERA was eight percent below league average. In New York he had much better teammates, which meant they scored more runs for him and the defense behind him was superior. Predictably, Pennock started to win in pinstripes, and he went to the World Series four times. His record as a Yankee was 162-90, but he never pitched as a true ace, his ERA+ in New York was 114, which is the same as Jon Matlack and Luis Tiant. Pennock did go 5-0 in the Fall Classic, but he also got six runs of support per game. He ended up winning nearly 60 percent of his decisions, but still managed only 241 wins and never led the league in wins, ERA, complete games, shutouts, or strikeouts. In 22 seasons the southpaw only led the league two times, once in winning percentage and once in innings pitched.

8. Chick Hafey

Chick Hafey only played as many as 130 games in a season four times in his career. Read that again, let it sink in. Hafey only had seven years of 100+ games. If you’re going to be out of the lineup that much you better be damn good. Chick had great talent, he was fast and had some power. But he only had 1,466 hits in his short career to go along with the .317 batting average. Hafey was considered one of the most exciting athletes of his era, he won a batting title. But that’s all he has. If we’re going to induct exciting players who combine power and speed, let’s give Eric Davis and Darryl Strawberry a plaque in Cooperstown.

Hafey ranks 62nd in our list of The 100 Greatest Left Fielders of All-Time, hardly a glowing endorsement for Cooperstown status.

7. Tommy McCarthy

Reportedly invented the hit-and-run and the practice of using signals between the base runner and the batter. Those innovations may or may not have actually come from McCarthy, but even if they did, it’s not a reason to elect this otherwise average player into the Hall. His career WAR of 16.2 is the lowest among position players in the Hall of Fame, and represents the same value as two seasons from Mike Trout. McCarthy hit .292 and he could steal some bases, but he’s a worse player than Carl Crawford, and has no business being in the Hall of Fame.

6. Lloyd Waner

If his name had been Lloyd Wilson, he never would have been elected to the Hall of Fame. Lloyd Waner was one-half of the famous sibling duo for the Pirates in the 1920s and 1930s, with brother Paul Waner.

Lloyd was a Mickey Rivers, Coco Crisp type player. He hit some singles (lots of singles), and he could run. Otherwise he was a below average player. He does not rank among the Top 100 Center Fielders of all-time. Had he not been “Lil Poison” to brother Paul’s “Big Poison,” Lloyd would be forgotten.

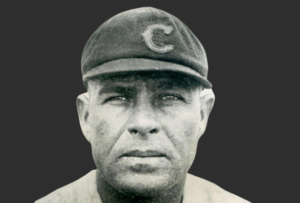

5. Rube Marquard

In 1912, rubber-armed Rube Marquard won 19 straight games for the Giants. That streak gave the lefthander great notoriety, and seems to be the basis for his selection in 1971 by the Vet Committee led by Frisch. Other than that streak, Marquard’s career record was 182-177, and it should be noted that he pitched more than half his career with great teams, which helped him get that many wins. His career ERA+ of 103 is the lowest for a Hall of Fame pitcher, and rates below Fernando Valenzuela and Frank Tanana, to name two better left-handers.

4. Jesse Haines

Ol’ Pop Haines was elected when he was 77 years old in 1970 after Hall of Fame Veterans Committee chairman Frank Frisch (his former teammate) pulled some strings. Haines pitched for the Cardinals for 18 of his 19-year career, but managed only 210 victories for good teams. Haines pitched for five St. Louis teams that won the pennant, but averaged only 12 wins per season in those years. He was just another pitcher in their rotation: in fact the Cards only gave him four starts in those five Fall Classics. There are more than one hundred pitchers not in the Hall of Fame who were better than Haines.

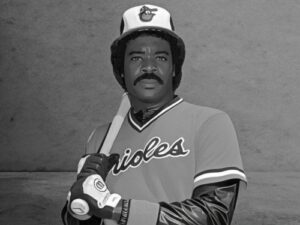

3. Harold Baines

Led the league in slugging once, and that’s it. Came up as a promising right fielder with the White Sox but evolved into a professional bat-for-hire designated hitter. Was talented enough to play 22 seasons and get more than 2,800 hits and 380 home runs.

Harold Baines had zero signature moments. He never had an outstanding season. He was just a very good hitter for a number of years, and a well respected guy in the clubhouse. There’s a lot of merit in that, and more than 2,800 hits is amazing, but Baines was usually designated hitter who piled up RBIs because he was fortunate enough to be in the middle of the lineup. There’s nothing extraordinary about his run production, and he didn’t add any value with his glove or legs.

Jerry Reinsdorf, the man who owned the ChiSox when Harold came up, helped convince eleven other members of the Today’s Game committee to check a box for Baines. His puzzling election (after never receiving more than 33 votes from the baseball writers) lowers the bar for hitters in the Hall of Fame as much as the next selection lowers the bar for pitchers.

2. Jim Kaat

Jim Kaat‘s election is strange, because the former left-hander was never even the ace of the pitching staffs he was on. He was usually an innings-eater, and to be fair he was an above average innings-eater who had 1-2 very good seasons. But otherwise, Kaat was just there, filling up a rotation for about 15 years until he transitioned into a middle inning relief specialist.

Kaat’s main credentials for the Hall of Fame come down to this:

- He won 283 games

- He garnered 16 Gold Glove Awards

- He is a longtime broadcaster

In 25 years as a major league pitcher, Kaat accumulated 50 Wins Above Replacement (includes his fielding and hitting contributions). That means he was roughly a 2 WAR player, maybe 3 WAR in a good season. In fact, he had 14 seasons where he had less than 1 WAR. That’s the most by any player (by far) who has been elected to the Hall of Fame.

Basically, Jim Kaat was a durable, effective pitcher who could field his position, and he spent about 15 years in a four-man rotation, which allowed him to get a lot of decisions. That led to 283 wins, which is an impressive figure, but it doesn’t change the fact that he was a fairly unexciting and unremarkable pitcher.

1. Freddie Lindstrom

The third player on this list who played with Hall of Fame second baseman Frank Frisch (with Jesse Haines and Chick Hafey). Freddie Lindstrom is the third man on this list who got into the Hall because Frisch pushed for his election.

Lindstrom was elected in 1976, a few years after Frisch had passed away, but the veterans committee rewarded him largely based on Frisch’s recommendations over the years.

Lindstrom only had eight seasons where he played as many as 100 games. He was a boy wonder, becoming the youngest man to play in the World Series, at the age of 18. In 1928 he was excellent, batting .358 with a league-leading 237 hits, 39 doubles, 107 RBI. That’s a very good season, and Lindstrom, a third baseman, finished second in NL MVP voting. Two years later he hit .379 with similar numbers, but in 1930 everyone in the NL had a great year with the bat. That season, the league hit over .300, and Lindstrom never hit higher than .319 in any other season.

His career was short (only 1,747 hits), he never won a batting title, and only topped 200 hits once. He rates 73rd among our Top 100 Third Basemen of All-Time.

There are more than three dozen third basemen not in Cooperstown who were far better than Lindstrom, who played his last game at the age of 30. Bill Madlock won four batting titles, Carney Lansford had 300 more hits than Lindstrom and also won a batting title. A very close match is Howard Johnson, who had a similar career length and peak. Do you think HoJo belongs in the Hall?

RELATED

Members of the Baseball Hall of Fame >

The Hall of Fame Case for Roger Maris >

The Hall of Fame Case for Dick Allen >