It seemed as if much of the nation was pulling for the Washington Nationals in the 2019 World Series, completed on Wednesday when the Nats prevailed in Game Seven.

The Astros grew into an unlikable team for a few reasons. First, they’re just too damn good. Only two years ago they won the World Series, and 2019 marked their third straight year over the century mark in victories. But the Astros also shot themselves in their own foot, Texas style.

After clinching the pennant, the Astros were in full spin mode after one of their front office employees shouted and instigated against female reporters in their clubhouse celebration. Whether you were disgusted by that incident or not, whether you thought it was something or a whole lot of nothing, it stained the Houston team, and the way the front office handled the mess was sloppy.

Later, it was revealed that the Astros used an illegal sign-stealing scheme during the 2017 season, in what may be one of baseball’s worst scandals of all-time.

As a result, much of America was ready to crown the Nationals, who were seeking their first title. Just like in 1924?

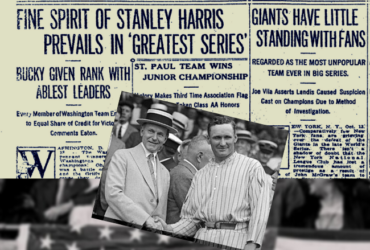

Senators were sentimental favorites in 1924 Fall Classic

There’s an old saying that goes “familiarity breeds contempt.” The World Series in the early 1920s started to look like a Broadway production. In 1921, 1922, and 1923, the series matched the Giants and Yankees against each other. The New York teams shared the same ballpark for the first two years, so every World Series game was played in the Polo Grounds in 1921 and 1922.

For three straight years the country watched two New York teams battle for supremacy in the baseball world. You get tired of that, and people did.

The Senators won their first pennant in 1924, and they did it with an amazing team. Many fans across the country were enamored with the possibility of Washington winning their first title and breaking the New York spell.

The ’24 Senators were the oldest team in baseball, but they were led by a boy manager. It was like first-year wizard Harry Potter guiding his fourth-year quidditch teammates to triumph.

The boy wonder was Stanley “Bucky” Harris, the 27-year old second baseman who also served as manager. Harris was a peppery character and a natural leader. He was in his first season as Washington’s skipper, and he improved their win total by 17 games to grab the pennant. The team was tied with the Yankees with a week-and-a-half left in the season before pulling away to deny the pinstripers a fourth straight flag.

The lineup featured two future Hall of Famers in the outfield, one of them 22-year old Goose Goslin in left, the team’s leading hitter. The other was sage Sam Rice, a 34-year old right fielder known as “Man O’War” because of his speed.

But the star of the team was Walter Johnson, the greatest pitcher in baseball history. Johnson was 36 years old but still won 23 games, and led the league in strikeouts and earned run average. They called him “The Big Train”, and he had the best fastball of his era. In a time when most pitchers couldn’t get their best pitch to 90 miles per hour, Johnson threw his heater at 95+ with regularity.

Johnson was not just a great pitcher, he was a gentleman. And so, many baseball fans rooted for him and the Senators to defeat the Giants, who had won two of the three previous World Series.

Scandal turned their own fans against Giants in 1924 World Series

The bloom was off the rose for the New York Giants late in the 1924 season. By the time the G-Men hosted the middle three games of the Fall Classic, many of their own fans were openly booing them.

At the conclusion of the Series, The Sporting News wrote that “great crowds at the Polo Grounds [were] rooting wildly against the once loved Giants.”

But why would fans root against their own team? One report stated that of the 50,000-plus fans at Game Three, half were cheering for the Senators. The reason was sketchy.

Late in the regular season, with the Giants in a pennant race with the Dodgers, New York was home to face the lowly Phillies in a three-game series. A sweep would virtually guarantee the flag to the Giants, which is why Jimmy O’Connell did what he did.

Why was Jimmy O’Connell? He was an outfielder for the Giants, and he proved to be very naive. Prior to the first game with Philadelphia, O’Connell approached Heinie Sand, the Phillies’ shortstop, asking if $500 would be enough for him to avoid “bearing down hard” against the Giants. It was a blatant attempt to bribe Sand to throw the games. Giants’ coach Cozy Dolan was also in on it with O’Connell, and may have even come up with the idea.

Sand told his manager and his manager told the team owner, and so on until baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis heard the news. Eventually the story broke and the attempted bribery was in sports pages across the country. It came out later that O’Connell may have been an unwitting go-between in a scheme hatched by Dolan and possibly others on the Giants, but regardless, their names were in the papers for the wrong reasons. New York fans, still remembering the game-fixing scandal that scarred the World Series five years earlier, where disgusted.

Further complicating the matter was the indecision of Landis, who refused issue any statements on the controversy before the World Series. The Giants entered the Fall Classic with a serious, serious public relations problem hovering over them. Everyone was suspicious of their motives, including their own fans.

The Washington Nationals are the first D.C. based Major League Team to win the World Series since 1924. While a lot of years passed in between the two titles, each time Washington came out “first in baseball” to go along with “first in peace” and “first in war” (once famously said of Washington the man), they also had the country pulling for them.