How many home runs did Babe Ruth hit? Which teams did Ty Cobb play for? Did Barry Bonds use steroids?

These are all questions that baseball fans might want the answer to. Where do they turn for answers? If they rely on Google, they may be disappointed.

According to a report from Hitwise, more than 60 percent of all Internet searches are made by smart phone. Many of those are made by voice search commands. Just pick up your phone and ask “How many bases did Ty Cobb steal?”, and Google will spit out an answer. That’s if you’re using an Android phone with standard settings in place. (If you have an iPhone, your experience may differ.)

But thanks to something called Google Knowledge Graph, you might be getting incorrect or biased data when searching for baseball players on Google.

Here’s a Search Results Page for “Ty Cobb stats” via Google:

You clearly see that Google thinks Ty Cobb played two seasons for the Kansas City Royals. If you click the name “Royals” you’ll be sent to a SERP (Search Engine Results Page) for the Kansas City Royals.

How does Google make this embarrassing error worthy of Bill Buckner? Well, I’m sure it has something to do with their database mistaking the Philadelphia A’s (whom Cobb played for in 1927-28) for the Kansas City A’s. Since the Kansas City A’s ceased to exist more than five decades ago, Google’s Knowledge Graph is trying to fill it in with something they think matches. They do this because they figure it’s useful for end users. But obviously, the result is not satisfying because it gets history wrong.

You can’t see it, because the screenshot above is clipped off, but Google shows Cobb with 4,189 hits too. Oh boy, here we go again. That number is incorrect (at least it’s unofficially incorrect), as MLB has ruled that Cobb had 4,191 hits. This makes it clear that Google is probably getting their baseball stats for these pages from Baseball Reference, which also has the wrong career hit total for Cobb.

Similar to their incorrect results for Ty Cobb, Google gets it wrong for Walter Johnson, the greatest pitcher of all-time. According to Google, Johnson pitched for the Minnesota Twins, not the Washington Senators, as we all thought he did.

Google’s Knowledge Graph has been around a long time. The search engine unveiled it about six or seven years ago. Why? Because Google wanted to improve the results for users and give them answers to their search queries quicker. With data culled from Google Knowledge Graph, there’s no need to click through to a search result to see when Theodore Roosevelt died for example, or when Father’s Day is, and so on. Over the years, Google has gradually added more data.

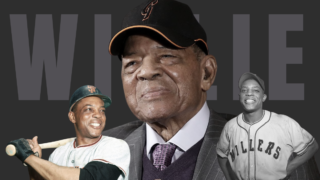

The layout you see on Cobb’s page, and the one below for Barry Bonds, reveals a standard SERP for a celebrity athlete.

You’ll note that on the left side of the SERP results, Google provides a sidebar with a photo of Bonds and quick links to Stats and Videos. This is similar to what you’ll see for many athletes (current and retired), as well as other famous folks.

Note that on the right side of the page is a Knowledge Box that provides a blurb from Wikipedia and a list of basic facts about Bonds, like his height, birthplace, even the names of his children. This data is culled from sources by Google’s search bots.

Why isn’t Google telling us about Barry Bonds and steroids?

More troubling about the Bonds page is the fact that Google allows the subject of the search to “claim ownership” of the search results. Just above the sidebar on the right that shows a short bio from Wikipedia, you’ll see a link to “barrybonds.com.” This means that Barry Bonds and his official website have claimed this Knowledge Graph data and they can request that Google alter it or show what they want.

Why is this troubling? Why does this matter? Here’s why: if you take a close look at the SERP for Barry Bonds, it’s not what you see that’s most interesting, it’s what you don’t see. Nowhere on the page is there a mention of steroids or performance-enhancing drugs. Nowhere does it mention the cloud of controversy that hovers over Barry Bonds. You might think this search results page is just a nice, tidy summary for a celebrity like Justin Timberlake.

The format that Google uses in conjunction with their Knowledge Graph is problematic for at least three reasons:

- They are prone to present incorrect information, such as the stats of Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson, and many others.

- The inclusion of data and content from other sources removes the need by the user to go to the websites for those sources. As a result, the user doesn’t see that information in context, and can’t make up their own mind as to the validity of that information. Also, as has been reported by others, websites like Wikipedia have lost millions of page views (and revenue) due to Google’s inclusion of their data on their results pages.

- Lastly, if celebrities, athletes, and institutions can manage their own search results, where is the objectivity? When would a celebrity ever include negative or contrary opinions on their search results pages? How can we trust the content we see on Google’s SERP?

At the very least, this article is intended to show you how some baseball stats could be wrong if you rely on Google to show them to you. But further, I hope it helps you see how Search Engines and their results, can skew the way we see things.

As a baseball and military researcher, the results that Google provides is more than troubling especially when they allow subjectivity and ignore cross reference and data sourcing. Pop-culture and hearsay reign supreme when quantifiable facts and (supported disputes) are available.

This is, perhaps one of your most important articles and will unfortunately be ignored by readers who want the hashtag answers and by Google who can’t fit sourced results into their graphs.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts, and for reading our blog.