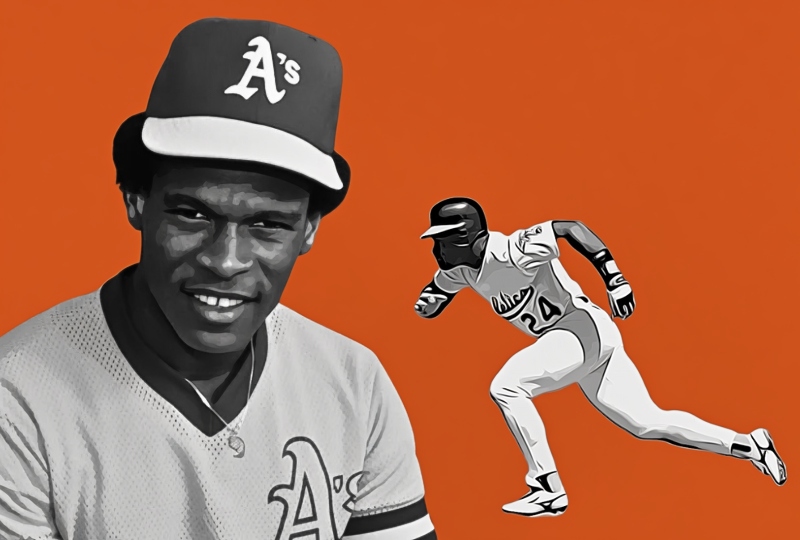

“There’s nobody who can win a game in as many ways as Rickey. He can walk in the first inning and that turns out to be the turning point of the game.” — manager Billy Martin

Just five days before what would have been his 66th birthday, Rickey Henderson has died. The Hall of Famer transformed baseball with his legs and dynamic style of play.

Henderson is a pivotal figure in the history of baseball. He was a seminal talent. He is the all-time leader in runs scored and stolen bases. He is universally acknowledged as the greatest leadoff hitter in professional baseball history.

No details on the cause of death were revealed, but the National Baseball Hall of Fame and the Oakland A’s confirmed that Henderson died on Friday.

RELATED: 100 Greatest Left Fielders in Baseball History

Rickey Henderson was scouted by an off-duty policeman who used to scour the sandlots in Oakland for talent. The scout suggested the A’s take a look at an undersized 17-year old Henderson, and a few months later Charlie Finley drafted him in the fourth round out of Technical High School. Prior to being signed as a professional baseball player, Rickey’s favorite sport was basketball. That summer he hit .336 in Boise in Low A-Ball, and he batted .345 with 95 stolen bases the next season for Modesto when he was still only 18 years old. He got to the big leagues in 1979 and stayed for more than a quarter of a century. He established records for runs scored and stolen bases. But he could have added even more to those totals had he been allowed to keep playing.

Henderson turned 40 years old on Christmas Day in 1998. A few weeks earlier he signed a one-year contract with the Mets, the team happy to employ him as their five-days-a-week left fielder. Rickey rewarded them: he hit 30 doubles, 12 home runs, batted .315 and had a .423 on-base percentage. His favorite thing, scoring runs, Rickey did that too, touching home plate 89 times. He stole nearly as many bases (37) as his age.

Left alone in a free market that would allow for direct unregulated competition, 40-year old Henderson should have been one of the most valuable properties in the sport. He was relatively cheap, he was still as productive (or moreso) than many of the higher-paid players in baseball. But a shift was happening in the game that had the unintentional consequence of edging Henderson out of the market. Revenue sharing and steroid use put pressure on teams to hire one-dimensional power hitters. Rickey just wanted to play, but his skills were pushed to the margins.

In 2000, Henderson stole 36 bases and got on base 190 times in 519 plate appearances. His walk rate was higher than four of the top six MVP finishers in the National League. But his power was decreasing, and he only had 20 extra-base hits. He was still a very useful offensive player, but teams wanted power hitters. Rickey managed three more years as a spare outfielder. At 42, he walked 81 times in 123 games, scored 70 runs, and swiped 25 bases for the Padres. But by this time, the value of the stolen base was under attack. Prevailing wisdom said that unless you were successful 80 percent of the time, a stolen base attempt was not worth it. Baseball valued a walk more than it ever had, but somehow Henderson was misjudged by the men in charge. To them, he was just a funny old ballplayer who talked about himself in third-person.

Rickey just wanted to play forever

If Henderson had played 70 years earlier, he might have played (and played regularly), into his late 40s. His tentpole skills, which were drawing walks, stealing bases, and baserunning, were still at about 90 percent of his peak in his 40s. He could have hit .220 and still been a plus-player. In fact, when he was 42 in San Diego he hit .227 but with a .366 on-base percentage. His OPS+ was essentially league average and he stole 25 bases. The next year he had basically the same year despite playing sporadically.

It’s ironic that the one team in baseball at the time that recognized undervalued assets, that lived on the margins, was the Oakland A’s, Rickey’s spiritual home. But Billy Beane never answered Rickey’s calls. Henderson played for five teams in his last five years, got no serious offers to continue, and played three more years in independent leagues. When he was 45 and 46 years old, he stole 53 bags in 57 tries. He was still drawing walks, he was still touching home plate. Ultimately, in 30 professional baseball seasons, Rickey walked 2,688 times and scored 2,780 runs.

“I was having fun,” Henderson said. “Most people were saying, you know, ‘[Do] you get tired of it?’ But I was having fun because it wasn’t [really about] what are you doing on the field? Were you going out there giving yourself 100 percent and doing the best you can and enjoying it? And when the day is over, you can tip your hat and say I gave you everything I got today. And that’s what kept me going.

“If they would have kept letting me play, I’d probably still be playing today.” Rickey said that in 2010, when he was 51 years old.

After Rickey Henderson broke the career record for runs scored, he asked the Padres if he could have home plate as a keepsake. Home plate is set deep into the ground, held in place by a pole a few feet long. To unearth home plate, the Padres had to schedule it for the offseason because Rickey had scored the record-setting run in the final homestand of the year. A few days after the season, the Padres had a small number of staff on hand to dig up the trophy. Rickey waited patiently with officials from the San Diego front office as a member of the grounds procured his prize. When the plate was retrieved, Henderson took it in his hands and held it above his head. He circled the field, making mock crowd noises and yelling “RICKEY HENDERSON! THE GREATEST OF ALL TIME!”