Here are the top 20 players in the history of the Philadelphia Phillies, according to Wins Above Replacement. (Note: this article was originally written in 2017)

His last name was pronounced CREW-VATH. His nickname came from the Spanish word gaviota, which means “seagull.” During a game in Mexico in 1904, Cravath hit a baseball that hit and killed one of the white birds. The fans took to hollering “gaviota” every time he came to the plate for the rest of the series. The name stuck and was shortened to “Gavvy.” The bird wasn’t impressed. Before that incident, people called him Cliff Cravath.

Allen is one of the most deserving candidates for Hall of Fame election. At this point, nearly 40 years after his last game, Allen doesn’t have a chance in hell of making it. But he was a better hitter than 90 percent of the players in Cooperstown as position players, and he’d easily rate in the top half of all Hall of Fame players in overall ability as a player.

Once before a game, a teammate by the name of Frank Thomas, a hotheaded, broad-shouldered man who was a veteran of the league, ribbed Allen while the two stood around the batting cage. The 23-year old Allen didn’t appreciate the joking at his expense and he and Thomas went at it, eventually being pulled away by teammates. In typical fashion, Allen was painted as the bad guy by the press. Thomas later apologized. It was an example of how humorless Allen was, how set apart from his teammates he was. In that era, in the racially-charged 1960s, Allen was very sensitive and aloof. Later, with the White Sox and Phillies for a second stint in the 1970s, Allen was a clubhouse leader and teammates appreciated his generosity as a veteran. Bill James famously ripped Allen in a long essay in one of his Abstracts, but in that case the historian was poorly mistaken.

The athlete who’s the first to do something usually seems remarkable. If they do it well enough, they can be startling to the senses. Babe Ruth was the first man to regularly swing for the fences and make good on his intentions. The tall farm boy Cy Young was the first to throw the baseball really hard overhand. In track and field, Jesse Owens was the first to combine blazing speed with incredible natural strength. Wilt Chamberlain was the first man so tall who was not clumsy and awkward, who was so unusually gifted that he seemed like a freak from another planet. It was Dr. J who made the dunk an art, and Michael Jordan made soaring toward the basket a thing of ballet-like beauty. Today, Steph Curry is the first man to make shooting long-range jumpers look simple.

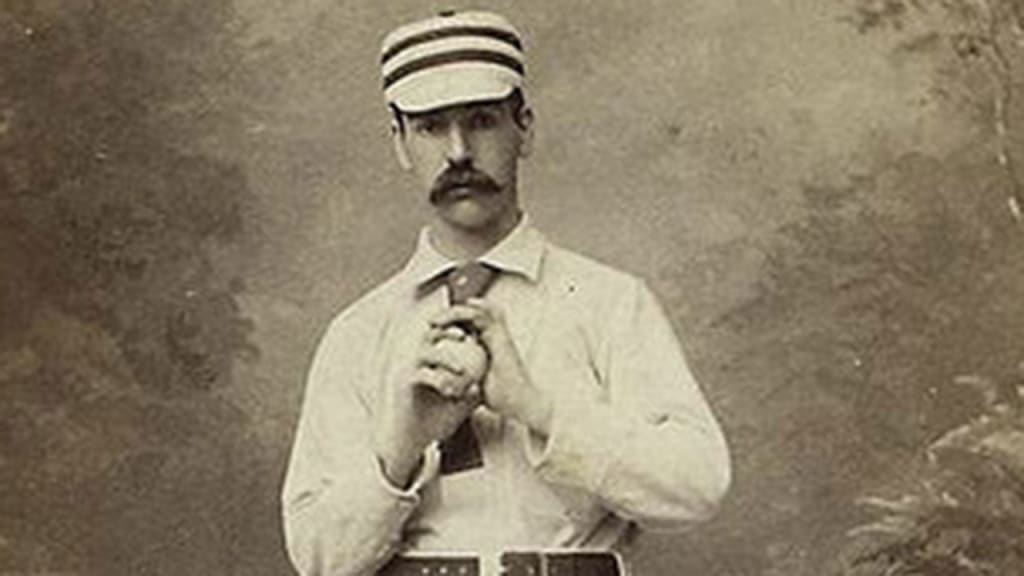

Ed Delahanty, Hamilton, and Big Sam Thompson played together in the greatest outfield of the 19th century, left to right. One season they all hit over .400. Another year they each scored at least 150 runs. Imagine having three of the top ten hitters in the league all playing for you in the outfield for about five years. That’s what the Phillies had in the 1890s.

Hamilton, by the way, was not a little man, as has been erroneously stated by other sources. Sure, he was only 5-foot-six, but most people in the 19th century were under 5-foot-nine. He weighed about 170 pounds in his prime and he had thick powerful legs. That’s a lot of weight for a man that short, so he was a little bit like Rickey Henderson: an explosive, strong athlete in a smaller package.

In Billy Hamilton, the Phillies had the best leadoff man of the 19th century. In Roy Thomas they had the best leadoff man of the first decade of the 20th century.

Like Hamilton, Thomas was a center fielder, but he was much more sure-handed. Thomas was tall and thin, almost stick-like. He crouched down in his stance, held the bat low, and had a superb ability to recognize pitches and foul off the ones he didn’t like. As a result, Thomas walked a lot, leading the league in that category five times in a row and seven times in eight years. But he could only be relied upon to get himself down to first base. In his nine full seasons with Philly, he got to first via a single 1,218 times, via walk 929 times, and via the hit-by-pitch 65 times. He had only 124 extra-base hits in those nine seasons, an average of 13 per year. He never once hit a baseball over an outfield fence in fair territory in the big leagues, all seven of his home runs were inside-the-parkers. He frustrated opposing pitchers, once fouling off 27 pitches in one plate appearance. He angered the normally calm Christy Mathewson by getting three bunt hits off him in one game, the only three hits the legendary hurler allowed to Philadelphia that day.

A rule change was reportedly made in part because of Thomas. His ability to foul off pitches led the NL to institute the foul-strike rule which mandated that the first two fouls hit by a batter were counted as strikes.

Thomas was a Philadelphia native and a popular player during his time with the Phillies. Three times during his career the hometown fans feted him with his own special day, and his rooters in the outfield liked to shout “Tom Tom” after Roy made a catch.

Callison was born in a tiny town in Oklahoma called Qualls. It was barely a town, more of a speck on a map, founded out of necessity when some folks traveling west had their wagons break down. By the time Johnny was 13 he was playing sports with the grownups in the area, a region in Oklahoma dominated by an Indian reservation. Because he was a superb athlete and he was from Oklahoma, Callison drew the natural comparisons to Mickey Mantle. He was never that good, obviously. But Johnny could run like the Oklahoma wind, he had a strong throwing arm, and he had some power with the bat in his hands.

The pivotal moment in Callison’s professional career came after the 1959 season when the American League champion White Sox determined that they needed to shore up their infield and dealt Johnny to the Phillies for Gene Freese. That year, Freese had socked 23 home runs and seemed poised to develop into an All-Star at the hot corner. But White Sox scouts must have missed Freese in the infield, and in his one season in the Windy City, he committed 20 errors in only about 115 games at third, most of them errant throws. Freese was gone the next year. Callison played the outfield, mostly right field, for a decade in Philly, making four All-Star teams and earning MVP votes three times.

In 1964 Callison finished second to Ken Boyer in MVP voting despite hitting .274 with a .316 OBP. His OPS wasn’t even in the top twelve in the league, but he still earned two first-place votes. That’s because back then the best player on a team in contention always got serious consideration for the award. The next season, a shortstop named Zoilo Versalles won the AL MVP when he did little more than play good defense and lead the league in doubles and triples. It’s not like that now. Now in baseball, you need to put up eye-popping numbers to win to get MVP support.

Callison was a great right fielder. He led the NL in assists several times in the 1960s and usually led the league in doubling runners off base. But he was overshadowed by Pittsburgh’s Roberto Clemente, who won every Gold Glove Award from 1961 through 1972.

The most important postseason performers in Phillies history:

If you wanted to construct an all-time team for the Phillies (who have been around as a franchise going back to 1883) the roster would have a strong modern flavor. Six of the eight starters would have played for Philadelphia after 1980, four of them in the 21st century.*

Rollins is one of them, he’s clearly the greatest shortstop to ever play for the Phils, surpassing Larry Bowa and a fella named Mickey Doolin, who played his last game for Philadelphia in 1913. Doolin was best known for his ability to throw the baseball across the diamond from many different angles and even used a quasi-sidearm-underhand delivery at times. Bowa was popular with fans, unpopular with his teammates, pretty mediocre in the field, and not a threat with a baseball bat in his hands. His most memorable traits were his ability to lay down a sacrifice bunt and his fondness for a perm.

Rollins holds the Phillies record with a 38-game hitting streak that spanned the 2005 and 2006 seasons. Only seven other players, all of them in the Hall of Fame, have had longer streaks.

*Bob Boone (catcher), Ryan Howard (First Base), Chase Utley (Second Base), Rollins (Shortstop), Mike Schmidt (Third Base), and Bobby Abreu (Right Field).

At the 2005 All-Star Game held in Detroit, Abreu hit something like 25 home runs in one round, a ton of them in a row. It was quite a show. I was sitting in the auxiliary press area in the right field stands as the left-handed batter launched pitch after pitch into the night sky. The baseballs were crashing all around us. Eventually one of the shots landed to my left and I watched as a writer reached forward to catch it but failed. The ball bounced away as the table and the table adjacent to it and the table in front of it all flipped over, sending drinks, hot dogs, lap tops, and startled sportswriters flying. Still one of my favorite moments covering baseball.

There have been far more lopsided trades in the last twenty-five years than there were in any twenty five-year stretch in baseball history, I think. I don’t have the research to support that claim, but it seems self evident. Jeff Bagwell, Pedro Martinez, Curt Schilling, Roger Clemens, and Miguel Cabrera all slipped from the clutches of teams only to go on to do superstar things for their new clubs.

On November 18, 1997, the Devil Rays traded Bobby Abreu to the Phillies for shortstop Kevin Stocker, a former top prospect. Stocker was a switch-hitter who as a rookie in 1993 came up and won the starting job at short with the Phillies and helped them to the pennant by hitting .324 in half a season. He never did anything like that again, never developed the pop the Phils hoped he would. In fact he never had more than 33 extra-base hits in a season. Abreu played nine years in Philadelphia and got MVP votes in five of those seasons. He was a fantastic player: he could do all the five things. The Phils made a mistake when they traded him to the Yankees before he could “get old” at the age of 31. Bobby had five more solid years after leaving Philly.

In some ways he was like Jose Cruz, also a corner outfielder who toiled anonymously on teams with bigger stars and had five-tool skills. Both players were excellent base stealers. Abreu has one of the best success rates of players with at least 400 stolen bases.

In the post-integration era, among right fielders, Abreu’s 138 OPS+ in his first ten seasons ranks tenth. The first time he was given a chance tom play every day he posted a 135 OPS+, so it’s obvious he was ready to be in the lineup before he was 24. Had either of his first two teams played him in his early twenties, Abreu might have picked up the 500+ more hits he needed to get near 3,000 and he would have certainly topped 300 homers, 600 doubles, and 1,500 runs and RBIs. Couple that with his 400+ stolen bases and his Gold Gloves and Bobby would have a strong Hall of Fame case.

If the requirement for greatness is to rank at or near the top among your contemporaries, then Sherwood Magee deserves more acclaim.

For a decade, from 1905 to 1914, he was in the top ten in home runs, RBIs, and batting average a total of 19 times. He led the NL in RBIs five times, slugging and total bases twice, extra-base hits three times, and in runs and hits once each. He was also a fast runner for a big man, swiping more than 380 bases. Unfortunately for him, he drew his paychecks from the Phillies (1904-1914), Braves (1915-1917), and Reds (1917-1919), three teams that rarely received much attention. Still, his numbers stand out in the record books, and in 2008, Magee was one of only five position players who played prior to World War II who were considered for election by a special Hall of Fame committee. None of the players received enough votes for election.

Magee was 35 years old at the end of the 1919 season, a frustrating campaign for the veteran left fielder in spite of it being the only time he ever played on a first place team. In April, Magee was felled by a serious illness, most likely mononucleosis, a virus that hits mature adults much harder than teenagers. He barely played for two months, returning to the first place Reds in August but sapped of his usual power. Cincinnati manager Pat Moran chose to play younger players in his outfield in September and in the World Series, passing over Magee even though he’d led the NL in RBIs the previous season. Sherry got two pinch-hit appearances in the World Series, delivering a single in Game Seven. A month after the Reds won the tainted Series against the Chicago “Black Sox,” they released Magee. Recovered from his illness, Magee spent seven years in the minor leagues against inferior pitching, once setting an amazing record when he reached base in 20 consecutive pinch-hit appearances. He contracted pneumonia in 1929 and died at the age of 44.

Most historians rate Ashburn among the top ten all-time defensively in center field. I’d rate them this way:

Maddox was called the “Secretary of Defense” because he was smooth and fast in the outfield. Someone once famously said “Two-thirds of the Earth is covered by water, the other third is covered by Garry Maddox.”

When Delahanty tumbled off a railroad bridge into the Niagara River in the dark early morning hours of July 2, 1903, he was one of the most famous athletes in the country. The 35-year old was the reigning batting champion, he was adored by countless fans in the nation’s capitol, and he was the oldest of the famed Delahanty Brothers, five strapping boys from Ohio who all went on to play professional baseball.

Delahanty was big for his time, nearly 6-foot, two-inches tall and a muscular 180 pounds. He was handsome and remarkably gifted in athletics of all sorts. He was usually the fastest, strongest, and most talented on the field of play in any sport. The Philadelphia Phillies boasted baseball’s best offense in the 1890s, a sort of Muderers’ Row of the Gilded Age, and Big Ed was the centerpiece. Sliding Billy Hamilton, Napolean Lajoie, Elmer Flick, and Big Sam Thompson were also in that lineup, all of them (with Ed) destined for the Hall of Fame. Delahanty could do more than sling the “ol’ wagon tongue,” he was also a fleet outfielder and he had a strong throwing arm. It was hard to take your eyes off him when he was playing.

As hard as he played on the field. Delahanty played hard off it. He enjoyed gambling, drinking, and playing cards with his buddies. But he was never good at drinking. In those times they called a man who couldn’t hold his liquor a “badger.” Big Ed piled up debts and enemies in towns across the east coast after he embarrassed himself more than a few times or failed to pay a debt. By 1902 his marriage was on the rocks, he was nearly broke, and he was drinking more often than ever.

On that fateful July evening in 1903, a conductor demanded that Ed leave the train bound for Buffalo after the ballplayer was involved in several disturbing incidents. A drunk Delahanty walked his way onto a bridge that was more than 25 feet above the Niagara River. After exchanging words with a night watchman, he fell (or jumped?) into the river and was not seen again for nearly a week when his naked, dead body was fished out of the water several miles downstream. He had went over the Falls and met a violent end. More than 20,000 people viewed his casket in Cleveland at a funeral ceremony. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.

How did Pete Alexander dominate the Yankees in the 1926 World Series when he was with the Cardinals despite being drunk? The answer to that question dispels a myth and reveals the different circumstances of professional baseball at the time.

Quite simply, Alexander was not drunk when he entered Game Seven of the ’26 Series in relief. He was tired, worn out, and epileptic. Ol’ Pete lived a rough life, he was a troubled man who succeeded in baseball ins spite of his inner demons.

From about the age of 25, Pete Alexander always looked at least ten to fifteen years older than he was. By 1926 when he was 39 he was an old 39. Heck, 39 in 1926 was like being 60 today. People didn’t take care of their bodies back then like they do now, and Alexander was never concerned with his physical health beyond his right arm because he didn’t think he’d live to see 40. There’s an old saying: “If you’re a hard liver, you’ll have a hard liver.” That was Alex.

The second point about Alexander’s stellar performance in the 1926 World Series is the independence of the two top professional leagues. By the mid-1920s the National League and American League had been bound together by a united contract for more than two decades, but it was a tenuous co-existence. The two leagues still hated each other. John McGraw was still very much alive and managing his Giants, and he never had any use for that goddamn other league. Teams in rival leagues rarely traded players, rarely played each other in exhibitions unless money was involved, and did not work together more than they needed to. There was still very much the notion of “National League players” and “American League players.”

In the 1920s, the truce between the AL and NL was an uneasy one. The World Series was the only place where the two leagues got a look at the talent on the other side.

In the 1926 Series the Cardinals were facing off with the powerful Yankees and their “Murderers’ Row” lineup. Most experts tabbed the Yanks to win the battle handily. But the Yankees had never seen anything like Pete Alexander. The veteran could no longer throw his fastball at the top speeds of his prime, but his pitching technique and mound mastery were unique and baffling. The tall righthander whipped the baseball around his body and released it on a three-quarters or sidearm delivery, which made the ball seem to be going five to ten miles per hour faster. He used a fadeaway pitch he learned later in his career, his patented curveball, and a knuckle-curve that surprised batters and threw off their timing. In 20 innings against the Yankees, Ol’ Pete struck out 17 batters. They never had a chance.

Among the great second basemen, Utley ranks with Eddie Collins, Joe Morgan, and Davey Lopes as the best basestealers. After his 30th birthday, Utley stole 85 bases and was caught only nine times(!). He’s still getting playing time at the age of 38 for the Dodgers as I write this.

The test for second basemen to get into that circle of greats is to perform after their 30th birthday. Few have been able to do that. Utley fell off a bit after that milestone but he was still valuable because he was above average at so many things.

His 30.5 WAR after age 30 ranks 12th all-time at the position. Seven of the men in front of him are in the Hall of Fame, then there’s Sweet Lou Whitaker, Lopes, Jeff Kent, and Eddie Stanky.

Without those counting stats, it doesn’t matter what his peak was like, or that he aged fairly well. Utley may never sniff Cooperstown. In many ways though, he was the most important player on the Phillies teams that won five straight division titles and two pennants from 2007-2011.

Carlton was 35 years old in 1980 when he won 24 games and logged more than 300 innings to lead the Phillies to their first world championship. He was 37 in 1982 when he won his fourth (and final) Cy Young Award. That season he pitched 19 complete games. The following year at the age of 38 he led the league in strikeouts and won two games in the NLCS, allowing only one run as the Phils won the pennant. That team was so old they were known as the “Wheeze Kids” and won the second pennant in the Carlton/Schmidt Era.

There’s probably never been another old pitcher (32 or older) who had more to do with their team getting into the postseason than Lefty. Without him, there’s no way the Phillies win the World Series in 1980, and they don’t get into the postseason in two of the next three seasons either.

Younger fans might not know this, but there was a really fun stretch in 1983-84 when Carlton and Nolan Ryan were taking turns as the all-time strikeout leader. Ryan broke Walter Johnson’s record first, then Carlton breezed past The Big Train. The two leapfrogged each other for about a year, depending on who had the latest start. It’s easy to forget, because Carlton had only 427 K’s in his last five seasons, while Ryan pitched until he was nearly a grandpa and had 939 K’s after Carlton retired even though he was only 24 months younger than the lefthander.

Few men knew the art of pitching better than Roberts. Late in his career while he was with the Astros he served as an assistant pitching coach, helping young men nearly half his age understand the craft.

He was a cerebral pitcher who used a “2-to-1” philosophy in which he demanded that he toss two strikes for every ball outside the strike zone. As a result, he led the league in K-to-Walk ratio a record five times and one year he pitched 330 innings and tossed 30 complete games while only issuing 45 free passes. He liked to make batters earn their way on base. As a result of throwing so many strikes, Roberts gave up a lot of home runs. When he retired, his 505 HR allowed were almost 100 more than any other pitcher in history. But 66 percent of those came with no one on base, so it rarely cost him.

Roberts was almost always the smartest guy in the room. He helped found the players’ union, which he fostered to become the most powerful labor union in the country. He was one of the guys who picked Marvin Miller to head up that organization. Even when he was young, Roberts was a step ahead of almost everybody. During his college career at Michigan State, he coached intramural teams in five sports and was a team leader in every endeavor he tried. He was the captain of the Spartan basketball team that won the Big Ten title in 1947.

There’s little doubt that Mike Schmidt is the best third baseman in baseball history. Schmidt was a slugger, sure: he hit all those home runs and led the league eight times. He led the NL in homers when he was 24 and led in both homers and RBIs when he was 36. In both years he led the league in slugging too. He walked about 100 times a year which means his .260 to .270 batting average was even less important than that stat is. But in addition to that, Schmidt was a revolutionary defensive player. He was one of the first players at the hot corner who came in to field bunts and slow rollers barehanded and had the arm strength to fire the ball to first to get the runner. He had excellent range to his left, which only made the infield defense better (which was helpful seeing as how the mediocre Larry Bowa was next to him at short for several years).

Schmidt was still a really good player from age 33 to age 37, which is unusual for the position. Eddie Mathews’ last good year was when he was 33. Brooks Robinson was still a fine defender after 30, but he was a mediocre offensive player by 32. Home Run Baker stunk after his 32nd birthday, and most other top third basemen were either done or part-time players by their early 30s. That trend has flipped a bit in the last ten years or so, however.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.