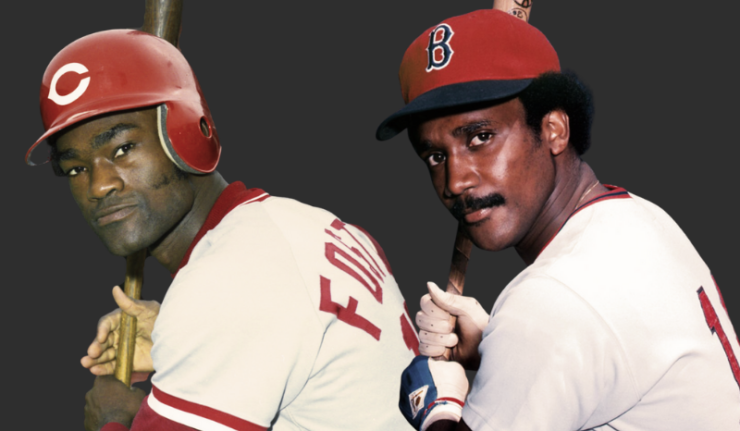

In 2009 after 15 years on the Baseball Writers’ ballot, Jim Rice was elected to the Hall of Fame. His journey on the ballot started at just under 30% and gradually climbed until he inched his way over the 75% threshold. His name will forever be immortalized in the plaque gallery in Cooperstown as one of baseball’s legends.

But why was Jim Rice inducted and not George Foster?

Foster spent four years on the Baseball Writers’ ballot and never got as much as 10% of the vote. He fell off the ballot in 1995, the same year that Rice appeared for the first time.

In this series of articles about the Baseball Hall of Fame, I’m going to compare a player not in the Hall with a single Hall of Famer. Let’s start by examining the two players.

Jim Rice: Red Sox Power Hitter

Rice was a first round pick by Boston in the 1971 MLB Draft. He signed out of high school in South Carolina, and quickly showed he was a good professional hitter. By 1974 he was in Boston playing with the Red Sox, and the following season (his true rookie year) he was one of the best rookies in baseball, hitting .309 with 22 homers and 102 RBI.

In 1977 he won his first home run title, and the following year he had a season for the ages, topping 400 total bases. He led the AL that season in 11 categories, including hits, triples, homers, RBI, and slugging. He was named league Most Valuable Player, getting 20 of the 28 first-place votes.

Rice had a similar season in 1979. He was at his peak, considered the most dangerous hitter in the American League, if not all of baseball. He won three home run titles in all, and he consistently ranked among leaders in hits, doubles, RBI, and total bases.

But Rice wasn’t a swing-and-miss, all-or-nothing slugger. He hit .300 seven times, with a career-best .325 in 1979. When he was 34 years old in 1986, he batted .324 with only 78 strikeouts in 157 games.

Rice was a strong man with broad shoulders and powerful legs. He was famous for quick bat speed and his right-handed swing, while packed with extra-base pop, was condensed and short. He was a pull-hitter with power to center field too. For much of his career he was an above-average baserunner, though he never learned to steal bases. But he was excellent at moving around the bases and aggressive, stretching singles into doubles and doubles into triples.

When he ended his career following the 1989 season, having played every game for Boston, Rice had 382 home runs to his credit, as well as 1,451 RBI in 2,089 games. He had a career batting average of .298 on 2,452 hits. He also kept his slugging percentage above the .500 mark, finishing at .502 for his 16 seasons.

George Foster: Quiet Man of The Big Red Machine

The egos in the Cincinnati Reds‘ clubhouse in the 1970s were tremendous. You had Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Tony Perez, and the mouthy manager Sparky Anderson. But the biggest ego belonged to Pete Rose, the cocky kid from Cincinnati who personified the Reds as they won four pennants in the 1970s.

Rose once said of his teammate George Foster: “George is in a class of his own—he and Mike Schmidt—as far as hitting home runs. But you have to do other things. You have to knock a wall down occasionally. You have to get your uniform dirty. I used to go through three uniforms a day. George uses three a month.”

Foster didn’t concern himself with knocking down walls and dirty uniforms. He was a power hitter, and his big (black) bat fit nicely in the middle of the Big Red Machine offense.

Foster was drafted by the Giants in the 1968 MLB Supplemental Draft after toying with college in southern California. He was one of many young talented outfielders the Giants had in the early 1970s, along with Bobby Bonds, Dave Kingman, and Garry Maddox. San Francisco sent him to Cincinnati for shortstop Frank Duffy and one other player in May of 1971. Mistake.

Foster took a few years to mature in Cincinnati, in part because Anderson didn’t take to his quiet, Bible-reading personality. But in 1975, the same season Jim Rice was terrorizing pitchers in the other league as a rookie, Foster caught a break that pushed him into the starting lineup.

By 1975 the Reds were more of a Big Red Disappointment than anything else. The team had won three division titles and two pennants in the first half of that groovy decade, but no World Series title. Sparky and the front office knew they needed something in 1975 to push the team over the top. In the first month of the season the team started sluggish, and by May 16th the Reds were under .500 and 5 1/2 games out of first. Something needed to be done.

That’s when Rose volunteered to move to third base, where the Reds were getting next to nothing from a slew of below average players. But that left a hole in Rose’s spot (left field), which meant Foster was in the starting lineup. After Foster entered the lineup, the Reds went 89-35 and ran away with the pennant. They won the World Series and repeated as champions in 1976. Foster hit 52 homers combined in those two championship seasons, and in ’76 he led the NL in runs batted in.

In 1977, Foster had his signature season. That year he belted 52 home runs, becoming the first player to top 50 since Willie Mays 15 years earlier. Foster was named NL Most Valuable Player and led the league in runs, homers, RBI, total bases, and slugging. The following year in 1978, Foster became the first man to lead his league in RBI three straight times in more than four decades.

Once he was given a chance to play regularly, Foster smashed home runs at a regular clip. He topped 20 homers ten times in eleven seasons from 1975 to 1985, and six times his slugging topped the .500 mark.

Foster signed a multi-million dollar contract with the Mets in the early 1980s that ended up being a bust for New York, and an albatross around the neck of George. The Big Apple was a lot different than Cincinnati, and Foster never learned to handle the media. He sulked when he got booed, he complained when he wasn’t playing, and fans couldn’t let him forget that he wasn’t hitting 50 homers a year any more. He retired during spring training in 1987 when no teams offered him a contract.

In an 18-year career, Foster hit 348 homers and had 1,239 RBI. He played in 1,977 games and batted .274 with a .480 slugging percentage. He was a good baserunner, very quick and long-legged. But he was only a fair defensive outfielder, really more of a designated hitter stuck in the National League.

Similarities between Foster and Rice

First let’s look at the similarities between Rice and Foster:

- Both were right-handed power hitters who pulled the ball very well.

- Both men were born and raised in the south.

- Foster and Rice were both quiet men who were uncomfortable with media attention. While both led by example with their play on the field, neither was a leader in the clubhouse.

- Both players were below average left fielders.

- Rice and Foster were both very good baserunners, but usually didn’t steal a lot of bases.

- Both played for teams with lots of star players, and they met each other in the 1975 World Series (won by Foster’s Reds).

- Rice and Foster each had their best seasons during the 1976-1979 period.

- Both players were league MVPs in the late 1970s.

Differences between Foster and Rice

Now let’s examine their differences, which should reveal the reasons the voters elected Rice to Cooperstown but not Foster:

- Rice entered the starting lineup as a rookie and he was one of the best rookies in baseball, finishing second in AL Rookie of the Year voting. Foster struggled to find playing time, was traded by the team that drafted him because they had other players they liked better at his position, and had to fight for attention on his next team because his manager didn’t like him. Foster didn’t become an everyday player until he was 26 years old.

- Rice was one-half of a heralded rookie tandem with teammate Fred Lynn. The pair, dubbed “The Gold Dust Twins” by sportswriter Peter Gammons, finished 1-2 in 1975 AL Rookie of the Year voting. Rice and Lynn were seen as the next generation to lead Boston to glory.

- The Red Sox had a long tradition of excellent left fielders, going back to Ted Williams and Carl Yastrzemski. Essentially, from 1939 to 1974, Boston had a Hall of Famer in left field. Rice was handed that baton, and with his success in his first few seasons, in a way he was elevated to their status in the minds of many. “The Red Sox always have a Hall of Fame left fielder, right?”

- The Reds had four massive superstars in their lineup in the 1970s: Bench, Rose, Morgan, and Perez. There was no way that Foster was going to usurp their star power. Even once he was given a chance to play, George was always in a lesser category. This is evident from the All-Star selections: Rice was an All-Star eight times, while Foster only made it five times.

- Rice drove in 100 or more runs seven times, while Foster did it three times. In four seasons, Foster drove in 90 but failed to reach the century mark. Voters like the 100-RBI season, and had George been able to get a few more of them, his numbers would look more impressive.

- The baseball writers were more impressed by Rice in his era: the Boston slugger finished in the top ten in MVP voting six times. Foster finished in the top ten four times.

- Rice hit for a high average, and Foster was seen as more of a slugger. Rice’s career batting average was .298. Foster’s was .274. Hall of Fame voters in the 1990s, the voters who considered the two players: they liked batting average.

- In his prime, Rice was considered the most feared slugger in his league, without any real challengers. In the National League, during Foster’s prime, there was Mike Schmidt and Dave Parker. Both of those players outshined George.

- Jim Rice played his entire career with one team, while George Foster had four different teams on the back of his baseball card.

Why Jim Rice is a Hall of Famer, but George Foster is not

The people who watched Jim Rice in his prime thought he was more dangerous and more productive than they did George Foster. Even though their numbers are somewhat close. Rice’s career OPS+ was 128, and Foster’s was 126.

But there are a few undeniable facts in favor of Rice:

- Foster had over 1,900 hits and 1,200 RBI, but Jim Rice had more than 2,400 hits and 1,400 RBI.

- Rice hit for that .298 batting average and he was the “next great Red Sox left fielder” following in the tradition of Teddy Ballgame and Yaz.

I’m fine with Jim Rice being in the Baseball Hall of Fame. I remember him being the most feared hitter in the American League for about 5-7 years, maybe a little longer. I think he was a better hitter than Eddie Murray at their peak, and he was at least as good a ballplayer as Kirby Puckett was. Rice has excellent numbers, though his career and peak numbers are not at the legend level. But not everyone needs to be a legend to be a Hall of Famer.

Foster was a fantastic hitter for several years. At his peak he was at Hall of Fame levels, but unfortunately he didn’t sustain it long enough into his 30s, and he suffered because he didn’t get a chance to play regularly until he had been in the majors for more than six seasons. If Foster had been able to crack the Cincinnati lineup when he was 23, maybe he gets over the 400-homer mark, and things are different.

RELATED

Top 100 Left Fielders of All-Time >

Cincinnati Reds All-Time Team >

You’re really, *really* splitting hairs if you think Rice is a deserving HOFer (which he’s probably not) but Foster isn’t. Career WAR of 47.7 vs 44.1. Yeah, WAR isn’t perfect, but in this case it gives us a very reasonable take that Foster was ~92% as good as Rice.

The “most feared hitter” blather is 21st century, revisionist, internet-echo-chamber nonsense. Judging by your byline photo, I’m older than you are. I don’t recall anyone’s commonly ascribing “most feared hitter” status to a player in Rice’s era. But if they had, Schmidt and Brett would have been at the top of their respective leagues.

You also vastly overrate the baserunning of both these guys. Neither was outstanding, and Rice led the AL in GDP four consecutive years. I also think neither was terrible, and Rice’s GDPs are largely a byproduct of (a) hitting hard grounders and (b) seldom walking. But to cite it as a strength is really grasping at straws.

Rice’s advantages over Foster as a HOF candidate come down to:

If he had played for, say, the Padres or the Astros, virtually no one would have made a HOF case for him.

You’re rude. You can make a comment without being a jackass. So, you’re older than me? So what? I guarantee I know more about baseball history than you ever will.

Yes, many people described Jim Rice as the most feared hitter in the American League, and all of baseball for a few years. That doesn’t mean he belongs in the Hall, I am merely describing what contemporaries thought of him.

You are in need of a class on how to read criticism: the premise of mt article was not to argue for Jim Rice over George Foster. It was meant to analyze WHY one player was elected to the HOF and the other was not, to help better understand the institution and baseball writers, etc.

Also, I didn’t cite GDP by Rice as a “strength.” And…you clearly don’t understand why a batter hits into DPs: it’s largely because he hits with a lot of runners on first base.

Try being nicer. Delivering your comment with far less snark would do you well.

If you don’t think George Foster was a well above average baserunner, and Rice wasn’t at least above average, you weren’t alive in the 1970s.

“If he had played for, say, the Padres or the Astros, virtually no one would have made a HOF case for him.”

You mean how no one made a case for Tony Gwynn or Craig Biggio or Trevor Hoffman, who played for the Padres and Astros?

You make a common mistake many fans make: you think there’s a bias for the east coast teams and Hall of Fame voting. There just isn’t. Not in the last 50 years anyway.

Here are some of the best players NOT in the Hall of Fame:

— Thurman Munson

— Don Mattingly

— Graig Nettles

— Roger Maris

— Keith Hernandez

— Andy Pettitte

None of them are in the Hall of Fame, and they all made their bones in New York. Most knowledgeable baseball fans would admit those are some of the very finest players outside of Cooperstown.

It took Goose Gossage nearly all 15 years to be elected. Gary Carter, one of the best catchers ever, and a Met superstar, was on the ballot for SIX YEARS.

You simply don’t know what you’re talking about if you think there’s a bias in favor of the Yankees, Red Sox, Mets and the Hall of Fame.

In recent years stars from the Padres, Expos, Rockies, Twins, Mariners, Blue Jays, Indians, and Rangers have been elected. Sure, the mega stars like Jeter, Ortiz, and Rivera get elected, but the Mets/Yanks/Red Sox don’t get any better treatment in modern HOF voting.

It helps the discussion if you know what you’re talking about.