In his first appearance on the Baseball Hall of Fame ballot, Bobby Abreu received just 22 votes. Last year he gained 13 votes to increase his share to 8.7%.

Abreu’s Hall of Fame case is complicated by a lack of eye-popping award achievements and magic milestones. He never once won a Most Valuable Player Award, and Abreu was only an All-Star twice. He won a single Gold Glove and he earned two Sliver Slugger Awards. But those deficiencies, while telling, are not the only part of the story.

Value Beneath the Surface

Like an iceberg, Abreu’s most impressive credentials lie below the waterline. Abreu did things that still, even in the age of Moneyball, get overlooked. He drew a ton of base on balls, he stole bases at a remarkable clip (76% in more than 500 attempts). He got on base and ran the bases as well as almost anyone in his era

Only 55 players have reached base 4,000 times in baseball history. Of those, just ten are NOT in the Hall of Fame, including Pete Rose, Barry Bonds” href=”/barry-bonds”>Barry Bonds, Rafael Palmeiro” href=”/rafael-palmeiro”>Rafael Palmeiro, Rusty Staub” href=”/rusty-staub”>Rusty Staub, Manny Ramirez” href=”/manny-ramirez”>Manny Ramirez, Omar Vizquel” href=”/omar-vizquel”>Omar Vizquel, and Dwight Evans” href=”/dwight-evans”>Dwight Evans. Two others, Álex Rodríguez and Adrián Beltré, have yet to get votes for the Hall. Rodriguez is in his first year on the ballot in 2022, and Beltré will be eligible in 2024. The tenth is Abreu, whose .395 on-base percentage is higher than any of those players other than ARod.

Ironically, Abreu’s most famous moment came doing something he wasn’t known for. At the 2005 All-Star Game in Detroit, Abreu launched baseball after baseball into the right field seats in an impressive display to win the Home Run Derby. He set a then-record for homers in that event. But Bobby wasn’t a home run hitter, not really. He spent his career being picky at the plate: he rarely strayed to swing at a pitch out of the strike zone. Like Joey Votto, Abreu was a patient, yet dangerous hitter.

Bobby and Vlad

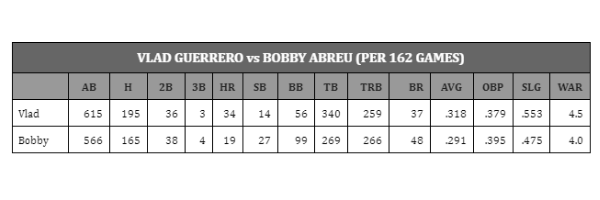

Vladimir Guerrero and Bobby Abreu were contemporaries, and while Vlad has a Hall of Fame plaque, Abreu probably never will. An argument can be made that Abreu was a superior player by the numbers, although by a slim margin.

Abreu was born early in 1974 in Venezuela, and 11 months later, Guerrero was born in the Dominican Republic. Both players debuted in September of 1996, but they didn’t become everyday players until two years later, both for teams in the National League East.

Both Guerrero and Abreu were high-average hitters with power, and they hit a lot of doubles and triples early in their careers. Abreu was a better base stealer, faster: he stole 400 bases. But Vlad stole 40 bases one year, the same season he hit 39 homers. Guerrero hit 30 homers eight times, Abreu only twice.

There were differences: Vlad was an aggressive bad-ball hitter, probably the best bad-ball hitter since Yogi Berra. He didn’t walk much as a young player, but he made good contact. In contrast, Abreu was picky: he averaged 109 walks in his first nine full seasons, and he didn’t mind striking out. Guerrero was right-handed, tall, and he had a long swing. Abreu was shorter, thicker, and his left-handed swing was compact. He was more of a pull hitter than Vlad, who could tomahawk the ball over the wall the opposite way.

Guerrero won an MVP Award, he was an All-Star nine times, and one of the most popular players in the game. Abreu was only an All-Star twice and performed poorly in MVP voting, despite having five 300/400/500 seasons. Abreu won a Gold Glove, but Vlad never did.

Vlad basically split his career between the Expos and Angels, though he had two quick seasons with the Rangers and Orioles. Bobby Abreu played at least two seasons with four teams, and played on six teams total. He was in two organizations before he became a regular in the majors, and in his last eight seasons he played on five teams. Late in their careers, Vlad and Bobby were teammates on the Angels.

Both Guerrero and Abreu were durable: Abreu had 13 straight seasons of 150+ games, and Vlad had nine in his career. As a result, they logged a lot of hits, runs, and RBIs. Both players had at least 1,300 runs and RBIs, and 2,400 hits. Each of them are among the few players to have at least 4,000 total bases.

What it comes down to is this: Guerrero had 71 more total bases per 162 games, but Abreu added about 16 more bases via his ability to get on base and run the bases. To oversimplify it: Bobby was the table setter, Vlad was the run producer.

Guerrero might have been a better player at his peak, but Abreu had a longer career and more value in total. If we limit the comparison to 1996-2011, the years they were both active, they are very close in career value, Abreu with 336 Win Shares to 332 for Vlad. Or by Wins Above Replacement, it’s Abreu 61-59. Their five best seasons (according to WAR) are dead even, 31.7 to 31.0, advantage(?) Vlad. The numbers say both played well in their home ballparks, in the case of Abreu much better. But that might not have been a case of favorable park factors as much as it was Bobby taking advantage of a good pull field down the right field line.

In our list of the Greatest Right Fielders of All-Time, we rate Vlad one spot ahead of Abreu. They both rate favorably with Dave Winfield, and well ahead of Tony Oliva, a right fielder who was recently elected to the Hall of Fame.

Vlad went into the Hall of Fame in his second year of eligibility, there wasn’t much discussion about his candidacy. He was such a marvel, so gifted in every area of the game, and he has that .318 lifetime average and 449 homers. Abreu didn’t appear on the Hall of Fame ballot until 2020, and he received just 22 votes. Once his supporters see he’s not a viable candidate, they will slowly drift away like a twig on a river.

Guerrero was more famous than Abreu and more important to the game in their time, and he’s deserving of his Hall of Fame honor. But strictly based on the value created between the lines, he and Bobby Abreu are close.

RELATED

The 100 Greatest Right Fielders of All-Time >

Philadelphia Phillies All-Time Team >

The 20 Greatest Phillies of All-Time >