In his senior year in college, Dave Winfield was a wanted man.

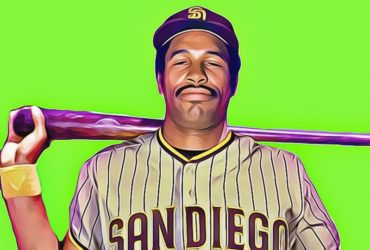

In 1973, Winfield, a senior at the University of Minnesota, was selected in four drafts in three different professional sports. Just weeks after being selected as the fourth overall pick in the baseball draft by the San Diego Padres, Winfield was named Most Valuable Player of the College World Series.

Drafted Professionally in Three Sports

Though he had the opportunity to pursue a career in basketball (he was chosen by both the Atlanta Hawks of the NBA and Utah Jazz of the ABA in their drafts) or football (the NFL’s Vikings drafted him in the 16th round even though Winfield had never played a down of football in either college or high school), Winfield preferred baseball, under one condition.

“I wanted to play the outfield and be in the lineup every day,” Winfield says. “Had I been drafted by a team looking to me [as a pitcher], I might have considered basketball. Football was never really an option to me, but [the Vikings] looked at me as a tight end.”

In spite of his awesome college career on the mound, the Padres drafted Winfield based on his all-around athletic ability, and wanted him to play the outfield. In his senior year, the right-handed throwing Winfield was 9-1 with a 2.74 ERA for the Gophers, leading them to the College World Series semi-finals. A hard thrower, he struck out 109 batters in 82 innings.

That golden arm was valuable in the outfield as well, and it came with a powerful bat. When he wasn’t pitching for Minnesota, Winfield got into 45 games and batted .385 with eight homers and 33 runs batted in. He made just two errors in the outfield.

In contrast to today, when drafted players often hold out for astronomical guaranteed contacts or leverage their selection to end up with the team of their choice, Winfield was anxious to make his mark in the pro ranks. After little hassle, he inked a $15,000 deal with the Padres, and negotiated a $50,000 signing bonus, most of which he invested in the stock market. His contract called for him to go directly to the big league club in 1973.

Years in San Diego as a Padre

Just weeks after ending his college career, Winfield was in uniform with the Padres, a team known more for their hamburger-chain owner Ray Kroc than for winning. That first season, manager Don Zimmer kept coaches away from Winfield’s swing (they wanted to alter his “hitch” that served as Winfield’s timing mechanism) and sheltered the rookie from tough pitchers.

“They were good at keeping me out against the Tom Seaver’s and Bob Gibson’s,” Winfield recalls. “I watched and listened, and tried to learn as much as I could.”

With competition for playing time fierce on the lowly Padres, and with teammates more concerned with their own jobs than helping along a rookie, Winfield often turned to opposing players for guidance, such as Billy Williams of the Cubs and Dick Allen of the Phillies.

“A few guys, [like San Diego infielder] Dwain Anderson, were helpful to me, showing me what to do as a big leaguer,” Winfield says. “But that was mostly off the field.”

MLB Draft Has Become a Media Event

On Tuesday, the first round of the draft will be covered live on MLB.com, and the top picks will ink contracts in excess of $1 million, most of it guaranteed money before they ever step onto a major league field for the first time. Winfield admits that times have changed for high draft-picks today, who can face hard feelings from their teammates, or added pressure to live up to the hype.

“The media was totally different. There was no ESPN, there was no Sportscenter. It wasn’t like ‘here’s a million-dollar bonus baby,’” Winfield recalls. “There weren’t any shoe contracts or endorsements.”

In fact, when Winfield suited up for his first big league game, he had to supply some of his own equipment.

“The Padres wore black shoes. I didn’t even have black shoes. I brought my white shoes from Minnesota and dyed them black.”

The talented Winfield collected hits in his first six major league games, and homered for the first time on June 21, off Ken Forsch of the Astros. He batted .277 with three homers and 12 RBI in 56 games in his rookie campaign.

Asked if he would have been able to handle the increased media scrutiny that exists today, and if a large signing bonus would have added pressure, Winfield didn’t hesitate.

“I’d have taken the money, and worried about the pressure later,” Winfield joked.

The Padres planned to send Winfield to the minor leagues the following year for some seasoning, but Winfield thwarted that schedule.

“When I arrived in spring training [in 1974] I worked hard and earned a spot on the team. I never went down,” Winfield said.

Winfield is one of the few Hall of Famers never to have spent a single day in the minor leagues. Whereas many ballplayers were taught the intricacies of the game at that level, Winfield learned on the job in the majors.

“I watched and studied,” Winfield says, “I always loved the game and it was fun for me, but there was so much to learn. I was amazed at how much you could learn about the game.”

A Hall of Fame Career

Winfield soaked it up like a sponge: by the age of 25 he was an All-Star, and two years later he won his first Gold Glove. He was on his path toward Cooperstown, which included stops in New York with the Yankees, California, Toronto, Minnesota, and Cleveland. When he retired he had more than 3,000 hits, 1,800 RBI, and a World Series ring with the Blue Jays.

But regardless of where he played, it was Winfield’s approach to the game that never wavered and helped him become one of the greatest right fielders in baseball history.

“I took the same approach even when I was the highest-paid player in the game. It didn’t matter if I had a one-year deal or a ten-year deal, I approached it the same. I looked at it as a game, and it was fun, but I worked hard to be the best I could.”