I don’t know nearly enough about the “guts” of WAR to know whether it’s great, good, bad, pitiful, or somewhere in between. This IS NOT an article to discuss the merits of Wins Above Replacement (WAR), it’s an article to discuss some great baseball players. The WAR thing is more of a gimmick.

Below is a list of the Top 20 Yankees as ranked by their Wins Above Replacement while in pinstripes (according to baseball-reference.com).

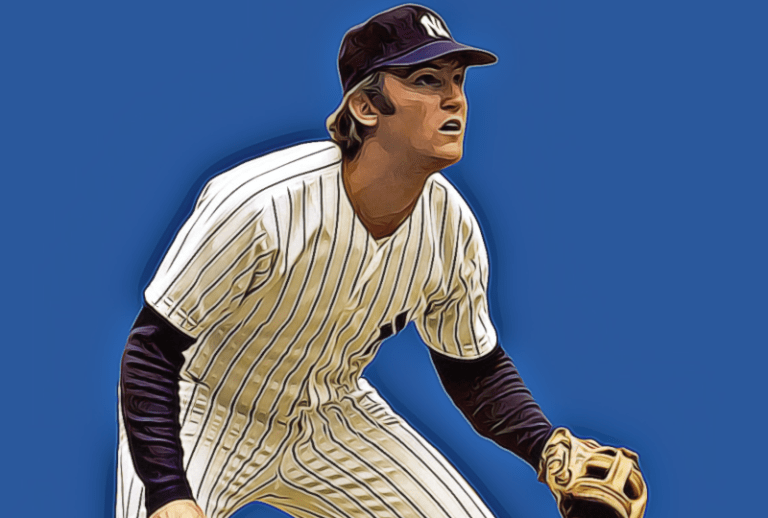

Nettles was the first third baseman I saw who had fantastic range to his left and routinely cut off ground balls that shortstops would normally get (or miss). I am really shocked he rates below Roy White, Thurman Munson, and Ron Guidry, all of whom were his teammates.

Here’s an incomplete list of baseball players named after other baseball players. For the purposes of this list, I’ve excluded those who were named for their father, like Pete Rose Jr. and Ken Griffey Jr., and so on. I’ve also not included those men who acquired a nickname from another player later in life, such as Babe Herman (from Babe Ruth) or Pudge Rodriguez (from comparisons to Pudge Fisk).

As of this writing, Cano has completed 12 seasons in the big leagues. He has 279 home runs and more than 1,000 runs and RBIs. He also has a career .306 batting average, though that will probably settle below the .300 mark by the time he hangs up his glove. He has a lot of things going for him that the Hall of Fame voters like. In 2016 he set a career record with 39 home runs, and it’s possible he could become the first second baseman to hit 400 homers. However, he is 33 years old and could end up being a designated hitter for the last stages of his career.

Even if he does eclipse the all-time mark for homers by a second baseman (379), the current record-holder (Jeff Kent) has not fared well in Hall of Fame voting. Kent has never topped the 20 percent mark in HOF voting in four tried through 2017. It’s unlikely he;ll get in via the baseball writers. There are similarities between Cano and Kent, beyond the fact they each have four-letter last names. People didn’t like Kent, he was considered a bad teammate, a selfish player, and a general jackass. Cano is aloof, arrogant, and is, according to a former Yankee teammate “A hard man to like.” Neither player was comfortable or capable of being “the man.” Both preferred to be part of an ensemble or as the “second dog,” though both had petty jealousies about the bigger stars they played with, Kent with Bobby Bonilla in New York and Barry Bonds in San Francisco, and Cano with Derek Jeter. Neither player was interested in developing their defensive game beyond just what they needed to stay at second base, and both players gravitated their offensive game toward home runs and RBIs, the big cash payoff stats. Both players had distant relationships with the press, Kent because he hated everyone, and Cano because he was embarrassed about the cultural difference. Both Cano and Kent hit a lot of homers and drove in plenty of runs in the post-season, but neither got a lot of credit for it.

Ultimately, I think Cano could hit 400 home runs and still not make the Hall of Fame. First, it’s a long shot he can do it: he’ll have to average 20 per year for his age 34-39 years. Most second basemen are toast by the age of 34. Cano doesn’t have the range (and doesn’t care to have the range) to play second any more. I see him moving to first base or DH pretty soon. Secondly, Cano has a lot of likability problems working against him. He’s been criticized for not hustling, for phoning it in, for being a selfish player. Lastly, for whatever reason, HOF voters have it in for second basemen. In addition to Kent, there are several very strong Hall of Fame candidates at the position that are getting shortchanged, including Bobby Grich and Lou Whitaker.

12 seasons

Johnny Bench

9 seasons

Mickey Cochrane

8 seasons

Gary Carter, Pudge Rodriguez, Mike Piazza

7 seasons

Yogi Berra, Ted Simmons

6 seasons

Bill Dickey, Joe Torre, Gene Tenace, Thurman Munson, Carlton Fisk, Jorge Posada, Joe Mauer, Buster Posey

Of the 12 players listed above who are eligible for the Hall of Fame, nine are in. The exceptions are Torre, Tenace, and Munson. All three of those players were active in the 1970s. They suffer from the Hall of Fame bias against catchers, which stems from the inability of baseball writers to recognize the physical rigors of playing the position. It’s very difficult to stay healthy and put up the numbers that Hall of Fame voters expect to see on the career totals line.

It’s fashionable to call White “underrated” – and I can point you to three of four articles from The Sporting News from the 1970s that mention White and use the word “underrated” a lot.

When I did my left fielder player rankings he kept coming up ahead of Jim Rice, no matter how I tweaked the formula. When I emphasized park effects, White would be ahead of Rice. When I de-emphasized career and emphasized peak performance, Rice nudged real close or even surpassed Roy, but White wasn’t far behind at all. It doesn’t seem like Roy White could possibly have had a more valuable career than Jim Rice (44.3 WAR), but it’s quite possible he did when you factor that Jim Ed was a DH for a long time. By the way, White was almost an exact match for Lou Whitaker as an offensive player. Sweet Lou was faster, but White ran the bases better.

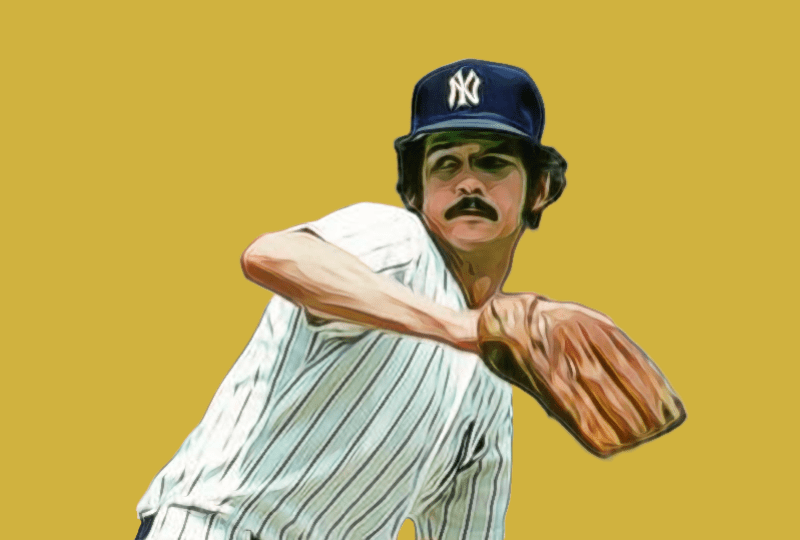

There’s a tendency (by fans outside of New York) to classify Guidry as a short-peak or even one-year wonder player. But of course, that’s not the case. He’s like a pitching version of Fred Lynn, who came into the American League at almost the exact same time. Both players had one awesome season (Lynn’s was in 1975) that overshadowed a lot of what they would later do.

In fact, Guidry pitched very well in 1979, the year after his big season, and he finished second in Cy Young voting in his 11th season at the age of 34, a year that ranks only fifth as far as WAR is concerned, for him. Similarly, Lynn had a second fantastic season (1979, when his offensive numbers were better than his MVP year), and then went on to have a lot of good to very good seasons the rest of his career. Both players were All-Stars several times, and both were important players in the AL from 1975 to the mid-1980s. Both are pretty good Hall of Fame candidates. Still, Guidry and Lynn are sort of seen as “disappointments” because they had such incredible peak seasons in their early years. Want a current player who might see the same narrative play out for his career? Try Bryce Harper.

There are five Yankee second basemen with at least 30 WAR: Lazzeri, Joe Gordon, Gil McDougald, Willie Randolph, and Robinson Cano. I’d rank them this way in career value:

CAREER VALUE, YANKEE SECOND BASEMEN

1. Willie Randolph

2. Tony Lazzeri

3. Joe Gordon

4. Robinson Cano

5. Gil McDougald

And now in peak value:

PEAK VALUE, YANKEE SECOND BASEMEN

1. Gordon

2. Lazzeri

3. Cano

4. McDougald

5. Randolph

That’s pretty much right, because Gordon averaged about 6 WAR per year in his six seasons as a Yankee, which is very good, while Lazzeri, who is a marginal Hall of Famer, put up a mark of 3.7 per in 12 seasons.

Why hasn’t anyone started a Willie Randolph for the Hall of Fame campaign? He was a better player than Phil Rizzuto (according to WAR and any other stat you might want to use), he played on four Yankee pennant winners, and he was adored by their fan base. Maybe it would help if he was a popular broadcaster for a few decades.

As I stated above in the Lazzeri comment, Randolph had the best career value as a Yankee, but his peak was not great. He was solid for 13 seasons in The Bronx, doing all the little things right, drawing 80 or 90 walks per season, stealing 15-30 bases, and handling second base with a graceful ease. He’s one of the 30 best second basemen of all-time.

Randolph suffered in comparison to contemporary Sweet Lou Whitaker, who was a better defensive player with a much stronger throwing arm. Whitaker was also good at taking walks but he had good power. While the two were competing in the AL, from 1978 to 1988, Randolph was an All-Star three times, while Sweet Lou made the team five times and won three Gold Gloves to none for Willie.

At least aesthetically, there are similarities between Rodriguez and Dave Winfield, who was also castigated for not being a winner in The Big Apple. Where Winfield was hated by Yankee fans because he wasn’t Reggie, ARod was resented because he wasn’t Jeter. Even when ARod was putting up far better numbers than Jeter, he wasn’t loved in The Bronx. When Jeter retired he was lavished with gifts all around the league, while Alex’s exit from the game came via an unconditional release and a hastily-called press conference. When he was at his best, Rodriguez was far and away a much better shortstop than Jeter, which is saying a lot because Jeter is a legitimate Hall of Famer. But that’s how good Rodriguez was, like him or not, clean or not.

I didn’t expect Dickey to rank this high, mostly because I look at his stats and see a lot of high average seasons, but not much else. But upon closer examination, his 15-25 homers per season during his peak are pretty damn good because back in the 1920s and 1930s 20 homers was an impressive total. He also walked more than he struck out and must have been (according to WAR) a good defensive catcher. His dWAR (Wins Above Replacement earned by his defense) was on the plus side in every one of his 17 seasons. It’s not clear that he wasn’t as good as Berra, but more on that later.

Dickey helped Berra learn the position when the younger catcher came along in 1946 after serving in World War II. The Yankees have had the following Hall of Fame succession lines over the years:

Catcher (35 years): Bill Dickey (1929-43, 1946), Yogi Berra (1946-63)

Second Base (21 years): Tony Lazzeri (1926-37), Joe “Flash” Gordon (1938-43, 1946)

Center Field (43 years): Earle Combs (1924-1935), Joe DiMaggio (1936-42, 1946-51), Mickey Mantle (1951-66)

From 1926 to 1946, with the exception of two WWII years, the Yankees had Hall of Famers at catcher, second, and center field every year. Talk about strength up the middle.

The only other team-position combinations that I could find that top 25 years are right field for the Detroit Tigers (Sam Crawford and Harry Heilmann for 27 years from 1903-1929), and left field for the Red Sox (Ted Williams, Carl Yastrzemski, and Jim Rice for an incredible 49 years from 1939-87).

Pretty amazing that a relief pitcher who averaged only 69 innings and faced about 270 batters per season, ranks this high in a counting stat that is supposed to measure overall performance. To me, it’s the most embarrassing ranking by WAR of the list.

Rivera is great (the best reliever I’ve ever seen) and anyone who is honest about it has to admit he’s the best to ever come out of the bullpen. But you mean to tell me that Mo’s career was almost as valuable as Berra’s, a catcher who was a key part of 12 World Series teams? I don’t buy that, based on the sum of his contributions as a reliever. Based on the 270 batters faced per season, that’s about nine starts for a starting pitcher. Even if ALL of the innings Rivera pitched were very crucial for the Yanks, I can’t see how a guy who pitches the equivalent of nine starts per season for 17-18 years has had a better career than say, Bill Dickey.

There are at least five Hall of Fame pitchers who used illegal pitches as a large part of their repertoire: Don Drysdale, Gaylord Perry, Bullet Joe Rogan, Don Sutton, and Ford. Of the five, Perry made the biggest show of it, using the threat of the pitch as a weapon. Sutton was masterful at concealing it, and he became very good at finding ways to make vaseline and other jellies impact the movement of the baseball. Negro Leaguer Rogan was a one-pitch stud who turned to the greaseball as an off-speed option. Even more so than Perry, Drysdale was an immensely gifted pitcher who used the spitball to augment his blazing fastball and curve. He was a mean sonofabitch who liked to have the spitball as another pitch to play off his heater.

Ford was the least talented pitcher of the five Hall of Famers who used the spitball after it was made illegal in 1920. When he was 20 years old and in the Yankee farm system he was a winning pitcher but didn’t dazzle anyone with his stuff. “I had a mediocre fastball and an okay curve,” he said years later. But Ford learned quickly to adjust his arm angle and speed, ultimately giving him what seemed to be an endless arsenal of pitches. Sometime in the late 1950s, Ford turned to tossing a spitter.

Ford was a breaking ball pitcher who loved to throw his curve, almost loved it too much. He once threw a complete game victory over the White Sox and told reporters after it that he’d only thrown five fastballs the entire game. In addition to his curveball, he probably threw a few scuffed balls in that one. Ford liked to cut the ball more than putting a substance on it, though he would do both. From 1961 to 1965, armed with his baseball-cutting techniques, his natural curveball, and a cunning intellect on the hill, Ford went 99-38 with a 2.85 ERA in the regular season for the Yankees, becoming one of the best lefthanders in the game in his 30s. In 1960 and 1961 he was a perfect 4-0 with a 0.00 ERA in four World Series starts, including three shutouts.

Among Hall of Fame hurlers, maybe only Dennis Eckersley achieved such a reversal of fortune simply by changing teams. In Eck’s case it was his meeting a new pitching coach and manager and embracing a new role with the A’s. In the case of Charles “Red” Ruffing it was the fact that he gained a potent offensive attack to support his efforts in New York, where the tall righthander also learned to pitch more efficiently, staying effective until he was in his 40s.

Ruffing had lost his job in the Red Sox rotation when he was traded to the Yankees a few weeks into the 1930 season. The Sox were so perplexed about his performance that they briefly considered making him an outfielder. The 25-year old had spent five years as a Boston starter with mediocre to horrid results. As a young pitcher in Fenway Park in the 1920s, Ruffing’s nickname could have been “BP” for as easy he was on the opposition. He gave up 303 hits one season and in 1929 he surrendered 280 hits in 244 innings while also walking 118 batters. He was essentially a fastball pitcher who had to tame his one good pitch to get it over the plate, which meant big league hitters smacked it around a lot. He was usually pitching from the stretch with runners on the bases. Boston was a very bad team, so Red lost a lot of games. His record at the time of his trade to the Yankees was 39-96. An all-time great he was not. Ruffing wasn’t even on anyone’s radar at that point.

But fortunately for Ruffing and the Yankees, Ed Barrow had a sentimental relationship with his former team and its owner. Barrow had once been in the front office for Boston and Red Sox owner Harry Frazee was still a friend. When Frazee had financial troubles, which was frequent, Barrow felt obliged to help him out, usually by stealing away his best players in return for the cash that Frazee so desperately needed. In most cases, Barrow poached good players, but the Ruffing deal was more of a favor to Frazee, and a strategic move for the Yankees. Barrow knew Frazee would want to auction players in the future, and by taking the struggling Ruffing off his hands for a throw-in player and $100,000, he was buying a place at the front of the line for future deals. If Ruffing could be remade into a serviceable Yankee, that would be a bonus.

Yankee scout Paul Krichel liked Ruffing’s fastball and his temperament. He advised Barrow that Ruffing could be made into a winner. It helped that at that time the manager was former Yankee pitcher Bob Shawkey, who had a knack for working with young hurlers.

In his first start for the Yankees, Ruffing led almost from the start, thanks to a first inning homer by Babe Ruth. The Yankees built a 6-0 lead for their new starter, which was fortunate because Ruffing gave up six runs too. But the Yankees and Ruffing still won the game over the visiting Tigers, 7-6. That was the first of 231 wins for Red for the Yankees as he plowed his way to 273 for his career. The Yankees were either first or second in runs scored in the AL in each of the first ten seasons Ruffing was with them. His record for that decade 175-95, and he won 20 games four straight years. He made himself into a good pitcher too, posting an ERA+ of 119 in his tenure with the Yanks. Not great, but pretty good, and good enough when your teammates are scoring 5-6 runs per game.

HIGHEST RUN SUPPORT DIFFERENTIAL, SINCE 1930

1. Lefty Gomez … 21.2 percent (above league average)

2. Spud Chandler … 17.4

3. Carl Erskine … 16.5

4. Red Ruffing … 15.5

5. Mel Parnell … 15.5

6. Preacher Roe … 15.0

7. Don Gullett … 14.3

8. Vic Raschi … 13.4

9. Gary Nolan … 12.1

10. Whitey Ford … 12.0

Italics denote pitchers who spent significant stretches of their career with the Yankees.

Ruffing started Game One of the World Series for the Yankees six times, it became somewhat of a tradition. He won five times, and the Yankees won the Series six times in the seven times they won the pennant with Ruffing in their rotation.

Ruffing became a famous and important starting pitcher in the 1930s and early 1940s, but he was not a great pitcher. He was a good-to-really-good pitcher who was the beneficiary of a great team around him. For the record, I don’t have a problem with Ruffing being in the Hall of Fame. There’s room for many types of players in the Hall, including those who were famous, important, and on many winning teams. Ruffing was the most consistent and dependable starter on one of the greatest teams ever (the 1936-39 Yankees), the first team to win four straight World Series. That matters.

Who was the least athletic looking superstar of all-time? Berra has to be on the short list, both for his strange appearance and his unorthodox hitting approach. Yogi was famous for swinging at pitches at his head. Others who come to mind are Randy Johnson and Honus Wagner. Here’s an all-time team of odd-looking great players:

THE “THEY DON’T LOOK LIKE STARS” ALL-STARS

C: Yogi Berra

1B: Harmon Killebrew

2B: Eddie Collins

SS: Honus Wagner

3B: Pete Rose

LF: Al Simmons (Maybe the worst batting approach of any great hitter. Think Kershaw but at the plate)

CF: Hack Wilson

RF: Tony Gwynn (potbelly era)

DH: Jim Thome?

SP: Randy Johnson

SP: Greg Maddux

RP: Dan Quisenberry

Berra’s career WAR is higher than that of Dickey, his predecessor, by about 4 wins. But Dickey had a better WAR per 162 games (5.3 to 4.9). It’s really a toss up, in my opinion, for best catcher in Yankee history. If you want a dominant peak, go with Dickey. If you want a better defender, take Yogi.

How good was Mantle? Jeter’s career WAR was 71, which is 38 fewer than Mickey. In other words, Jeter could have played an entire “half career” more and still been behind Mantle.

Jeter was scouted by Hal Newhouser, the Hall of Fame Tiger pitcher, who was working for the Astros in the early 1990s when the young infielder played high school baseball in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Newhouser begged the Astros to draft Jeter with the #1 pick in the 1992 amateur draft, and reportedly they considered it, but a lot of people in the Houston front office really liked Phil Nevin, and Houston took him instead. The Indians, Expos, Orioles, and Reds also passed on Jeter, so he fell to #6 and the Yankees. No one would know how good Jeter would be for about five more years, but Newhouser quit scouting for the Astros a few weeks after that draft.

You have to believe that if 28, 29, and 30-year old DiMaggio had been in a Yankee uniform instead of Army olive drabs in World War II, he would have had some of his best, if not his best seasons. DiMaggio had an off-year (by his standards) in 1942 before entering the Army. But it’s likely that he would have won at least one more MVP, giving him a then-record four for his career.

Consider what the Yankees lost during World War II, in terms of production. Their team, especially their lineup, was gutted, primarily for the 1943-45 seasons.

PLAYER (AGE IN SEASONS MISSED WHILE SERVING IN WW2)

Joe DiMaggio (27, 28, 29)

Joe Gordon (29, 30)

Phil Rizzuto (25, 26, 27)

Tommy Henrich (30, 31, 32)

Charlie Keller (27, 28)

Bill Dickey (37, 38)

Yogi Berra (19, 20)

Spud Chandler (34, 35)

Marius Russo (29, 30)

Can’t choose between DiMaggio and Mantle as the all-time greatest Yankee center fielder? If you want regal, royal grace, you take The Clipper; if you want the tape-measure homering good ol’ boy, you go with Mantle.

Babe Ruth was the greatest player of all-time. Another way to look at it, through the eyes of WAR: Ruth’s Yankee career was twice as valuable as Jeter’s (143 WAR t o 71 WAR for Jeter). Think about that.

Or there’s this: put three Ron Guidry’s in your starting rotation (47 WAR each) for 14 years and you get what Babe Ruth meant to the Yankees.

———

These great teams all have legions of fans who support their baseball teams by purchasing merchandise and tickets. Baseball pins are an essential part of a baseball fan’s expression of love. If you want some unique baseball products, you can do it through customization. You can customize a lapel pin with a picture of your favorite baseball elements on the GS-JJ.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.