This list ranks the 20 greatest players to have played for the Houston Astros, according to Wins Above Replacement (from Baseball-Reference.com).

This is part of a series of articles on the 20 Greatest Players for Each MLB Franchise.

The younger brother of Hall of Famer Phil, Joe was a superb pitcher who threw harder than his famous sibling. He had the knuckleball too (learned from their father), but Joe relied on his cut fastball and a spitball to win 224 games. He was 144-116 (.554) for Houston. In the 1980 Playoffs, he pitched a 10-inning shutout against the Phillies. A year later Joe pitched eight shutout innings to grab a win in the NL Division Series vs. the Dodgers. He had two shutout innings for the Twins in the ’87 ALCS. That gave Joe 20 shutout innings for a 0.00 ERA in the postseason.

Ryan didn’t pitch long enough in the Lone Star cap to move himself higher on this list. Though he was ninth in WAR for the Astros when he signed with the other Texas team for the 1989 season. Ryan tossed his record fifth no-hitter for the Astros in 1981. He’s had a falling out with the franchise since his retirement, and now pledges his allegiance to the Rangers, for whom he was once a front office executive.

Bob Watson was one of the kids the Astros rushed to the big leagues in the 1960s, along with Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub, and Jimmy Wynn. They switched Watson to left field, and traded first baseman John Mayberry to make room for Lee May. Watson was the best hitter of the three, and he hit everywhere: he batted .300 for all four teams he played for.

If you look close enough, there are similarities between Watson and Goose Goslin, the Hall of Fame left fielder. Both played the bulk of their careers in ballparks that were unfavorable to their power. Goslin played in mammoth Griffith Stadium in Washington D.C., and Watson played in the “Eighth Wonder of The World,” the Astrodome in Houston. Watson hit 50 more home runs on the road than at home, while Goslin was plus 64 in away games. Both were good contact hitters who drove in runs and played a corner position. Goslin was a superior hitter, clearly, while Watson was basically a high average power hitter with no speed. Both had animal nicknames, the folks called Watson “Bull” because of his thick, muscular body. Watson posted a higher OPS+ than Goslin by a few points, but Goose played in a high-offense era on famous teams as their RBI-man.

Watson was a poor defensive player, he was really a DH stuck in the wrong league. In 1977 he had probably his best season but he managed only four home runs in the dome (he hit 18 on the road). Had he played in a neutral park, Watson would have probably topped 35 homers a few times and gotten a lot more attention.

In the middle of his career, when he was with the Astros, Watson struggled through his worst season. A team official suggested he see an optometrist, and after an exam, the doctor informed Watson that he’d been wearing the wrong prescription all year. Watson got new glasses and the next season he was back in the All-Star Game.

“He can hit everywhere because he’s just a good hitter,” coach Eddie Yost said. “He’s got a short, quick stroke and is a contact hitter who is incredibly strong.”

Probably did throw a scuffed baseball, and it nearly carried the Astros to the 1986 World Series. An arm injury ended his career when he was 36.

Wilson was a hard-thrower and a hard-drinker. He was coming off his fourth consecutive 3+ WAR season when he died in mysterious circumstances a month before spring training in 1975. The righty had won at least 10 games in eight straight seasons for mediocre Houston teams. His death was ruled a murder/suicide (Wilson allegedly killed one of his young children before taking his own life). Had he not had the demons, Wilson could have continued into his 30s with J.R. Richard as a formidable 1-2 pitching punch for the Astros.

One of the great things about baseball is that on any given day a player can turn the page. The season is long, and with that type of schedule, players have the opportunity to climb out of a slump and start a hot streak. In the 2017 postseason that’s what happened to George Springer.

In the 2017 AL Championship Series, Springer went 3-for-26 against the Yankees, failing to drive in a run. Luckily, Justin Verlander pitched like the lovechild of Cy Young and Greg Maddux, and the Astros still managed to win the pennant. In Game One of the World Series, Springer stayed cold, going 0-for-4 with four strikeouts. He wasn’t in a hole, he was in a trench.

But in Game Two, Springer had three hits, the final one a two-run homer in the 11th inning to defeat the Dodgers. He hit four homers in the Fall Classic, one in each of the final four games of an epic seven-game battle. His five homers matched a Series record, and the Astros won their first championship. Springer hit .389 with a record eight extra-base hits in the World Series, and drove in seven runs. As a result, he earned the Willie Mays Award as MVP of the Fall Classic.

“It’s crazy,” Springer said. “I think as a player when things don’t start to go well, you tend to press. You tend to do things that you wouldn’t normally do. And after the first game I had a talk with Carlos Beltrán, and he told me to just go out and kind of enjoy the moment, because he’s been playing for 20 years and this is his second time here. He told me to go out and be who you are and kind of enjoy it.”

In the seventh inning of Nolan Ryan’s no-hitter on September 26, 1981, at the Astrodome, Mike Scioscia of the Dodgers hit a long drive to right-center that Puhl caught on the warning track. Ryan got his record-setting fifth no-hitter, and later admitted that Puhl’s catch was the closest call he had in all of his no-hitters.

Doran was intense, which was admired by his teammates and noted throughout the league. The Sporting News once wrote of Doran: “He leads the league in dirty uniforms and broken helmets.”

Probably the smartest ballplayer to step on a diamond in the last 60 years. Morgan was built a little like Jose Altuve, but a much, much better player. He could steal 60 bases, hit 20 home runs, win a Gold Glove, and hit .320, all of which he did. The Astrodome was dreadful for his offensive numbers, as it was for anyone who spent time there, and when Little Joe was sent to Cincinnati the sports world learned how incredible he was.

One of the five most important people in the history of the Houston franchise. Dierker won 20 games in 1969, when he received MVP votes. He was twice an All-Star for Houston, and later managed the team to four division titles in five seasons. He had a delivery a lot like that of Félix Hernández.

“One day I just want to sit in my house, spend time with my family, open a bottle of wine, and talk about these beautiful moments from playing baseball. I want to be able to show my son when he is older everything I was able to accomplish.” — Carlos Correa

Through his age 29 season, Bregman has two seasons of at least 7 WAR, something only 16 other third basemen have done. Most of them are in the top 25 at the hot corner. At 29, Bregman has essentially the same Wins Above Replacement that Brooks Robinson had at the same age.

Wynn generated tremendous power from his 160-pound frame because he dipped the bat quickly as a timing mechanism as he prepared to swing. He learned the technique from his father, and though more than one batting coach tried to change it, Wynn resisted. His record for home runs at the spacious Astrodome stood for more than two decades. From 1965 to 1974, despite playing in parks that suppressed power, Wynn’s 246 home runs ranked fifth in the National League. He hit more home runs than Tony Pérez during that span.

When he was pitching in the minor leagues in 1999, Oswalt hurt his shoulder, and might have torn something. A few days later he was checking the spark plugs on his truck when he inadvertently touched a wire and his truck started, sending a surge of electricity through Oswalt, whose hand was still on the plug. He reportedly held on to the plug for several seconds, until he fell away from the truck. According to Oswalt, after the incident his shoulder felt fine, and he never felt pain again. In a Sports Illustrated article years later, Roy told his wife, “My truck done shocked the fire out of me, and my arm don’t hurt no more.”

Berkman was one of the top prizes the Astros plucked from the amateur draft during a great run of drafting success from the late 1980s to the turn of the century. In 1987 the Astros drafted a catcher named Craig Biggio, the following year they drafted outfielders Luis Gonzalez and Kenny Lofton. In the next few years they nabbed pitcher Shane Reynolds, third baseman Phil Nevin, and relief pitcher Billy Wagner. By this time the Astros were winning division titles, but they continued to add talent, drafting high school pitcher Roy Oswalt, Berkman, college pitcher Brad Lidge, infielder Morgan Ensberg, and outfielder Michael Bourn.

Houston didn’t keep all of those players, but they shepherded a number of them to the big leagues where they wore the lone star on their cap.

One of the most unique ballplayers we’ve ever seen, for his size and offensive punch, Altuve has a chance to become the greatest “little ballplayer” in history. He’s a full inch shorter than Joe Morgan, the current holder of that title. Morgan won two MVP awards, and Altuve has one already through the age of 31. The “Pocket Cannon” has an outside chance to reach 3,000 hits and he could eclipse Morgan’s total of home runs plus stolen bases. Morgan was a better defender, and he was still a really good player late into his 30s, so it’ll be a challenge for Altuve to eclipse “Little Joe,” but not impossible.

When Altuve was 16 years old in Venezuela, he arrived at an open tryout but was turned away because he was too small. He persisted, coming back the following day with his birth certificate, and impressing the Astros enough to earn a signing bonus. Five years later he was playing second base in Houston, and he was an All-Star in his first full season.

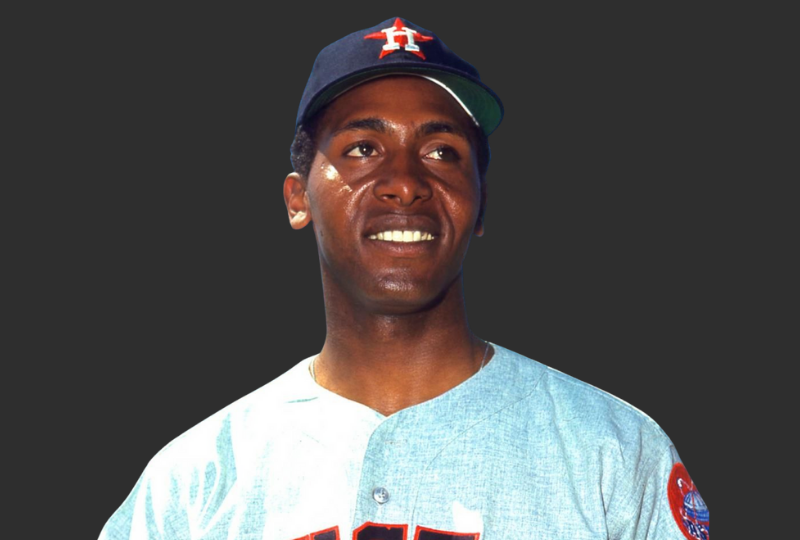

“When a player like Cedeno is on the other side, he’s a hot dog. When he’s on your side, he plays hard and is colorful.” — Maury Wills

Five 19-year olds have been starting center fielders in the big leagues. First was George Davis in 1890 in the old National League. Davis was a great athlete and was eventually moved to shortstop where he had a Hall of Fame career. The next was speedy Bobby Del Greco, who grew up in Pittsburgh’s Hill District and played as a teenager for the Pirates in 1952. Del Greco’s debut was a big deal, but his career wasn’t. Then came César Cedeño with the Astros in 1970, followed by Ken Griffey Jr. 19 years later and Bryce Harper in 2012 for the Nationals.

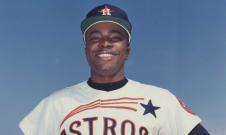

José Cruz was one of the best players to ever wear an Astros uniform. He never achieved superstardom because he played in the Astrodome, which negated much of his home run power. Cruz collected more than 2,000 hits and nearly 400 doubles, walked some, hit over .300 six times, and swiped more than 300 bases. In fantastic shape with his year-round schedule, he played until he was 40 years old. Describing his hitting philosophy, José said, “I go for choppers and bloopers.”

The career of Craig Biggio breaks down like this: four years as a catcher, 14 as a second baseman, and two as an outfielder. He was an All-Star as both a catcher and second baseman. Like most second basemen, Biggio hit the wall at age 34, which is why the Astros asked him to play center field. He wasn’t a particularly great outfielder, but he played every day and continued to churn out doubles.

Growing up in the northeast, Bagwell’s boyhood idol was Carl Yastrzemski. He retired with 449 homers, three fewer than Yaz.

Another random note related to the greatest Astro of all-time: Only two pairs of teammates played in as many as 2,000 games together: Ron Santo and Billy Williams; and Jeff Bagwell and Craig Biggio.

This feature list was written by Dan Holmes, founder of Baseball Egg. Dan is author of three books on baseball, including Ty Cobb: A Biography, The Great Baseball Argument Settling Book, and more. He previously worked as a writer and digital producer for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, as well as Major League Baseball Advanced Media.

No reproduction of this content is permitted without permission of the copyright holder. Links and shares are welcome.

No posts found!